The

Aarau–Bangalore Exchange (Part 2)

Dynamics of Self-Organization in the Making of Global Art Spaces

Shramona Maiti

Published on 14.10.2023

Artist Pierre-Manau Ngoula from Brazzaville, exhibition at the GARAGE,

Aarau, 2019. Ngoula was an artist-in-residence from July to September 2019.

Photo: Thomas Kern

Artist Pierre-Manau Ngoula from Brazzaville, exhibition at the GARAGE,

Aarau, 2019. Ngoula was an artist-in-residence from July to September 2019.

Photo: Thomas Kern

Aissa Deebi, 10 places to go while you’re in Aarau, Relief print on paper, on view at a temporary art space in Hintere Bahnhofstrasse, Aarau, 2005, as part of the exhibition marking the Arbeitsgruppe Gästeatelier Krone’s (GAK) ten-year anniversary of their artist-in-residence programme. Deebi, a Palestinian artist, was in residence at the GAK’s studio from January to June 2000. Image courtesy: Wenzel A. Haller

Adjaratou Ouedraogo from Ouedraogo, Burkina Faso, at a performance in Oerlikon (Zürich) in 2011. Artist-in-residence from July to September 2011. Image courtesy: Aargauer Kulturmagazin

The

main program of the GAK (Arbeitesgruppe Gästeatelier Krone or Working Group

Guest Studio Krone), as mentioned in Part 1 of this article, involved engaging

in cultural exchange with countries in the Global South—a network defined by

the inclusion of Palestine, Egypt, India, Jordan, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and

the Republic of Congo. This article provides the historical background for this

development, following which it explores the GAK’s exchange with Bangalore and

the life of the residency space in the neighborhood of Malleswaram.

EXPANDING CULTURAL HORIZONS: THE FORMATION OF THE GAK’S AiR NETWORK

Aarau,

in 1993, was a part of the newly formed state-supported organization called the

Konferenz der Schweizer Städte für Kulturfragen (KSK, or Swiss Cities for

Cultural Issues). The organization consisted of 33 Swiss cities that looked to

discuss and work on matters concerning cultural policy, with a significant part

of their program being dedicated to running foreign studios for artists in

Cairo (Egypt), Genoa (Italy), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Belgrade (Serbia).[1] Swiss artists nominated by their

respective cities could be hosted in these foreign studios for a period of

three and six months. Under the aegis of this program, the city of Aarau

nominated Haller, who was then practicing ceramics, for a six-month residency

in Cairo in 1993. As an artist-in-residence in Cairo, Haller was confronted

with the growing concern among Egyptian artists that they too should have the

opportunity to visit Switzerland and partake of a cultural exchange, thereby

prompting in Haller a desire to transform this one-way dialogue. When back in

Aarau, Haller brought together a group of people to form a housing co-operative

toward the end of 1994, calling it the Krone Genossenschaft.[2] Together they were able to purchase

some property in the beginning of 1995 within the city’s old town in a locality

called the Krone. Parallel to this was Haller’s efforts to form another group—the

Arbeitesgruppe Gästeatelier Krone (GAK, or Working Group Guest Studio Krone), a

collective from Aarau that included artists Christoph Storz, Marianne Kuhn, and

Daniel Furter, graphic designer Ueli Röthlisberger, curator Stephan Kunz, and

Elsbeth Bircher of the Aargauer Kuratorium, the art and cultural wing of Kanton

Aargau. The group came together upon agreeing that the cultural exposure of the

small and insular city of Aarau could benefit from hosting artists who came

from different cultures, especially from countries whose cultures of

contemporary art were largely underrepresented in the urban space of the city,

and also in Switzerland. At the same time, and while a member of the Krone

Genossenschaft, Haller had begun to propose the usage of some of the Krone

building space as a studio to host artists. Thus, by the end of 1995, as the

GAK was formed, it was also able to secure one of the apartments in the Krone

building to begin running their envisioned artist-in-residence program for

durations up to six months. Toward securing funds, the Swiss Arts Council, Pro

Helvetia, funded the initial ten years of the GAK’s AiR programs by supporting

the artists’ travel and stay; at the time Pro Helvetia did not have their own

artist-in-residence programs. The other regular body of support came from the

city of Aarau itself, which continues to pay the rent of the studio till date,

with later backing coming from the Aargauer Kuratorium.[3]

EXPANDING CULTURAL HORIZONS: THE FORMATION OF THE GAK’S AiR NETWORK

Choschthuus, a building with 16 apartments in the municipality of Rupperswil in Kanton Aargau, bought and renovated in the 1970s by a group of people including Haller, as part of a housing co-operative having around twenty members. Photo: Martin Froelich, 2023.

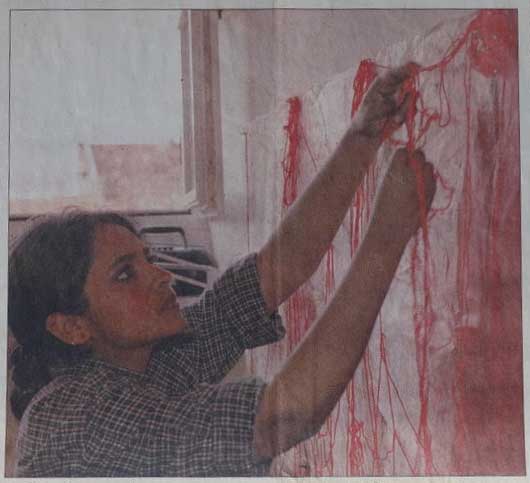

Newspaper clipping featuring artist Surekha at work at the studio in Kronengasse, Aarau, during her residency from January to June 1999. Aargauer Zeitung, 6 April 1999. Image courtesy: Wenzel A. Haller

While

the initial idea was prompted by the desire to host artists from Egypt in

Aarau, the program of the GAK developed differently with the entry of its other

collaborators. Officials at Pro Helvetia recommended that the GAK consider the

war-ravaged Palestine, where their situation had made it difficult for artists

to move freely across the globe. Thus, in 1996, Palestinian artist Rana Bishara

became the first artist from the Global South to participate in the GAK’s

program. Bishara was referred to the program by the artist-led Al Wasiti Art

Center based in Jerusalem. The introduction to this art center had, in turn,

come through cultural mediator Ursula Rindlisbacher, whose office in Cairo was

Pro Helvetia’s sole presence in the region now demarcated as the Global South.[4] India, as explored in the earlier

part of the article, was integrated into the GAK network in 1997, when

Bangalore was recommended as a site from where artists practicing contemporary

art could be invited. It would help challenge the prevailing perception of

India in Aarau as merely a producer of crafts with a visual culture limited to

inexpensive artifacts.

CREATING COLLABORATIVE CULTURAL BRIDGES

The artists who went to the GAK from Bangalore were Raghavendra Rao (1997), Surekha (1999), Prabhavathi Meppayil (2001), Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy (2003), Viswanath (2005), Smitha Cariappa (2007), and finally Nanaiah Chettira (2009). The selection process relied on recommendations from artist colleagues in the regions participating in the exchange, while also creating a network of artists involved in the decision-making process, as participants of the residency were often involved in choosing future residents. This approach has been maintained throughout the program’s history, ensuring a continuous cycle of collaboration. The six-month long residency format went beyond providing studio space for the visiting artists, as it aimed to give them an opportunity to deeply engage with Swiss culture and influence the community around them. Local Swiss artists played a vital role in guiding residency artists around Aarau and familiarizing them with everyday living in Switzerland. Haller even expressed how “the exchange between the residency artists and the normal, average local people is just as important.”[5] The artists were in frequent contact with non-artists to work out the details of their artwork and exhibition ideas, making this dialogue a crucial part of the process; for Haller, this becomes an essential aspect of cultural exchange, and where the residency still functions.[6]

CREATING COLLABORATIVE CULTURAL BRIDGES

The artists who went to the GAK from Bangalore were Raghavendra Rao (1997), Surekha (1999), Prabhavathi Meppayil (2001), Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy (2003), Viswanath (2005), Smitha Cariappa (2007), and finally Nanaiah Chettira (2009). The selection process relied on recommendations from artist colleagues in the regions participating in the exchange, while also creating a network of artists involved in the decision-making process, as participants of the residency were often involved in choosing future residents. This approach has been maintained throughout the program’s history, ensuring a continuous cycle of collaboration. The six-month long residency format went beyond providing studio space for the visiting artists, as it aimed to give them an opportunity to deeply engage with Swiss culture and influence the community around them. Local Swiss artists played a vital role in guiding residency artists around Aarau and familiarizing them with everyday living in Switzerland. Haller even expressed how “the exchange between the residency artists and the normal, average local people is just as important.”[5] The artists were in frequent contact with non-artists to work out the details of their artwork and exhibition ideas, making this dialogue a crucial part of the process; for Haller, this becomes an essential aspect of cultural exchange, and where the residency still functions.[6]

Newspaper clipping featuring artist Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy at the studio in Kronengasse, Aarau, during his residency from January to June 2003. Aargauer Zeitung, 22 April 2003. Image courtesy: Artist

Artist Viswanath at work at the studio in Kronengasse, Aarau, 2005. Image courtesy: Wenzel A. Haller

As

the exchange with Bangalore flourished, the local Swiss artists began

expressing interest in being hosted in India. With agreement from both sides,

the artists in Bangalore then arranged for a studio in Malleswaram, a centrally

located area in Bangalore, and the GAK bore the rent. In 2003 the first Swiss

artist, Michael Omlin, arrived in the Bangalore residency for a period of six

months, followed by others until 2007. Here, the residency period ranged from

anywhere between three to six months. While in Bangalore, the Swiss artists

engaged with local workers from the informal sector, specifically those who

provided handiwork and fabrication services like printing and tailoring. In

earlier formats of hosting foreign artists, such as those invited by the

Sarabhais, artists “were provided wide access to artisans and material,” with a

caveat that “they were never given the opportunity to mingle with the then

practising Indian artists.”[7] The Swiss artists’ involvement with

the local workers often went beyond the semantics of access to imbue

collaboration, with even a hint of influence. Artist Valentin Hauri, who spent

six months in Bangalore in 2003, had a memorable experience working with

signboard painters; he had engaged their services for the task of painting

words on a series of metal plates, following a schema of his design. To Hauri’s

amusement, the plates ended up adorned with thick linear borders, simply

because the border was essential to the aesthetics of the practice of his

painter-collaborators.[8] A similar experience was faced by Efa

Mühletaler, who came for three months in 2004 and worked with local tailors.[9] Her work was realized in

collaboration with young graphic designers and traditional tailors from

Bangalore; five design students, on commission, developed logos for a set of

virtues, which were then transferred to fabric by a tailoring studio. The

influence of the environment on the artists varied based on their unique

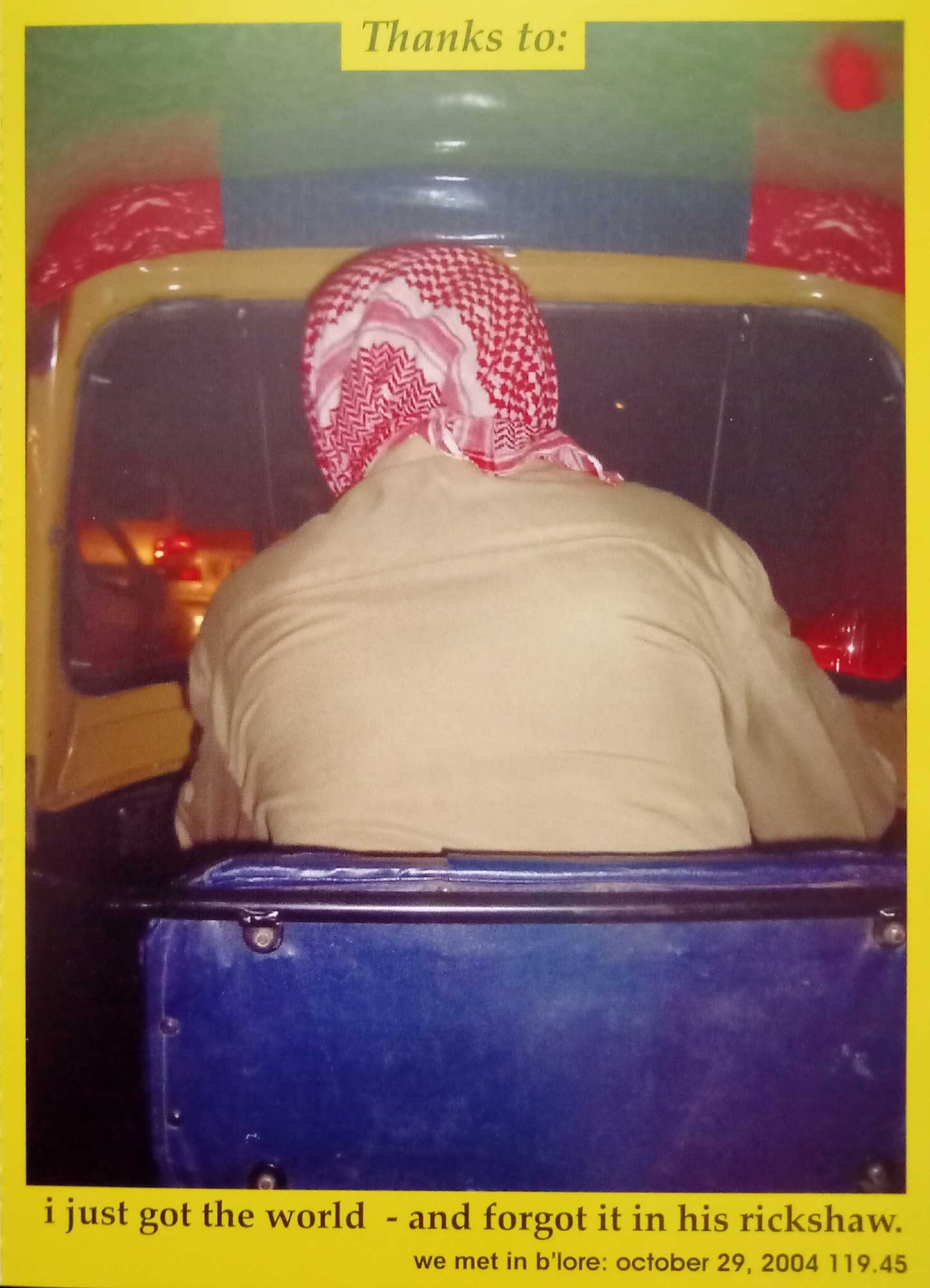

experiences of navigating the chaos of city life. Sabine Trüb, who stayed for

four months in 2004, was fascinated by the unusual appearance of gratitude

posts in newspaper classifieds, where families thanked their friends and

acquaintances for specific things, often including photographs. Trüb compiled

her own expressions of gratitude in the form of a book, which included images

of auto-rickshaw drivers who often had to navigate through heavy traffic in

Bangalore[10] When the artists’ stay culminated in

the form of final exhibitions, they made it a point to invite their

collaborators, who were equally enthusiastic about being a part of this

experience—one that was a tangible representation of their shared labor transformed

into works of art, and presented in the formal setting of a white cube gallery.

From left to right: Michael Omlin, Raghavendra Rao, and Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy gathered at a temporary art space in Hintere Bahnhofstrasse, Aarau, 2005. In August 2005, the Arbeitsgruppe Gästeatelier Krone (GAK) celebrated the ten-year anniversary of their artist-in-residence program, inviting artists Jumana Emil Abboud, Rana Bishara, Aissa Deebi, Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy, Marta Jakimovicz, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Charlie ‘Khalil’ Rabah, Raghavendra Rao, Ahlam Shibli, Surekha, and Viswanath. Image courtesy: Wenzel A. Haller

The

Aarau–Bangalore exchange came to an end in 2007.[11] By that time, the Malleswaram studio

had not only hosted artists from Switzerland, but also one from Palestine and

even one from India—Tushar Joag stayed for four months in 2002.[12] During this time, the studio also

played host to sessions that were part of the Mysore and Bangalore legs of the

Khoj workshops, which had been actively arranged for by Surekha and Raghavendra

Rao, along with Mysore-based artist N.S. Harsha. An integral part of the GAK’s

vision for the AiR program was to redress the paradigm of cultural exchange,

which had been “largely reduced to the import of paintings for exhibitions,” and

instead place people at the center of this exchange.[13] For the residency artists to fully

immerse themselves in a new cultural setting, the availability of fellow

artists in the foreign space came to be of paramount importance. In Bangalore,

with the increasing expansion of the city and notorious traffic, it had become

difficult for the local artists to travel frequently to Malleswaram when most

of them lived in distant corners of the city. This became a central concern for

the Bangalore artists as they decided to discontinue hosting Swiss artists. For

GAK, the idea of hosting Bangalore artists in Aarau had become intricately

linked to the notion of hosting Swiss artists in Bangalore; letting go of the

Malleswaram studio thus led to an overall termination of the exchange program.

Furthermore, a loosely formed Bangalore group of artists had begun to take

shape, who were now occupied with their own concerns of placemaking in the

city, which had a paucity of art spaces at the time.

Newspaper clipping featuring artist Prabhavathi Meppayil at work at the studio in Kronengasse, Aarau, during her residency from January to June 2001. Aargauer Zeitung, 13 June 2001. Image courtesy: Wenzel A. Haller

The

Malleswaram residency catalyzed the idea for the collaborative, artist-led BAR1

(Bangalore Artists’ Residency One), led by Surekha, Raghavendra Rao, Christoph

Storz, Ayisha Abraham, Suresh Kumar Gopalreddy, Smitha Cariappa, and Prabhavati

Meppayil. It took definite shape in October 2007, retaining the flexible

residency structure while being formalized as a public charitable trust. For

its first three years, BAR1 was supported by Pro Helvetia,[14] who had established their India

liaison office in New Delhi in 2007.[15] In 2008, BAR1 received a grant from

the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), which enabled the first edition of

their India–India residency that spanned six months. Residencies at BAR1 came

to an end in 2012, after having hosted at least a hundred artists from India, a

large number of foreign artists, and a few grantees of the Inlaks award.[16] Meanwhile, in 2003, Suresh Kumar

Gopalreddy, along with his artist-peers Archana Prasad and Shivaprasad S,

co-founded Samuha (“coming together”), a durational, 441-day curatorial

intervention in the form of a makeshift art gallery. Thus, the life of the Malleswaram

studio coincided with Bangalore’s steady transformation into an artist-led

economy of cultural spaces, which continued through the first decade of the

twenty-first century.

Sabine Trüb, Look at His Face: Rickshawdrivers of Bangalore, 2004, page from a book produced by the artist, designed by Anitha, printed in Bangalore. Image Courtesy: Author

CONCLUSION

At the end of the twentieth century, Bangalore was gaining global recognition for its meteoric rise in information technology, but it had little to no presence in the discussion of India’s art world. The infrastructure and a public for contemporary art were better visible in the cities of Mumbai and New Delhi, with their strong private art patronage and established positions in the canonized history of modern Indian art. The first encounter with Aarau and the GAK also came at a time when the Charles Wallace, Commonwealth, and Fulbright scholarships were the most widely available avenues for Indian artists to participate in foreign cultural experiences—a network where artists from Karnataka hardly saw any representation. However, today, the close networking of artists in Bangalore to birth a culture of alternative spaces in the city has earned it the moniker of a “solidarity economy.”[17] This mode of collective placemaking through artist-led networking not only situates the importance of the GAK as an exercise in cultural exchange, but also presents the Aarau–Bangalore exchange as an actor in the development of new internationalism globally—one that looked to challenge the nation-centric model of internationalism practiced by art institutions.

For several decades, the Swiss government had funded Swiss artists to participate in residency programs overseas, resulting in a one-sided exchange that the GAK aimed to address. In a letter to the Aargauer Kuratorium, Haller explained the GAK’s vision for inviting artists from regions such as Africa and India, citing the idea that new cultural developments and impulses often emerge from the periphery to the centers, particularly during times of stagnation in the centers.[18] These dialogues were taking place during the rise of artistic collaboration and socially engaged art seen globally in the 1990s, advocating for “art as a situation” over art as an end product of studio-based labor. This shift in artmaking practices was reflected in the GAK’s emphasis on the artist’s engagement with others during their residency, and their rejection of the idea of studio practice as an outcome-based process. They also made it a point to not retain any artworks made by the artists during their stay.

At the end of the twentieth century, Bangalore was gaining global recognition for its meteoric rise in information technology, but it had little to no presence in the discussion of India’s art world. The infrastructure and a public for contemporary art were better visible in the cities of Mumbai and New Delhi, with their strong private art patronage and established positions in the canonized history of modern Indian art. The first encounter with Aarau and the GAK also came at a time when the Charles Wallace, Commonwealth, and Fulbright scholarships were the most widely available avenues for Indian artists to participate in foreign cultural experiences—a network where artists from Karnataka hardly saw any representation. However, today, the close networking of artists in Bangalore to birth a culture of alternative spaces in the city has earned it the moniker of a “solidarity economy.”[17] This mode of collective placemaking through artist-led networking not only situates the importance of the GAK as an exercise in cultural exchange, but also presents the Aarau–Bangalore exchange as an actor in the development of new internationalism globally—one that looked to challenge the nation-centric model of internationalism practiced by art institutions.

For several decades, the Swiss government had funded Swiss artists to participate in residency programs overseas, resulting in a one-sided exchange that the GAK aimed to address. In a letter to the Aargauer Kuratorium, Haller explained the GAK’s vision for inviting artists from regions such as Africa and India, citing the idea that new cultural developments and impulses often emerge from the periphery to the centers, particularly during times of stagnation in the centers.[18] These dialogues were taking place during the rise of artistic collaboration and socially engaged art seen globally in the 1990s, advocating for “art as a situation” over art as an end product of studio-based labor. This shift in artmaking practices was reflected in the GAK’s emphasis on the artist’s engagement with others during their residency, and their rejection of the idea of studio practice as an outcome-based process. They also made it a point to not retain any artworks made by the artists during their stay.

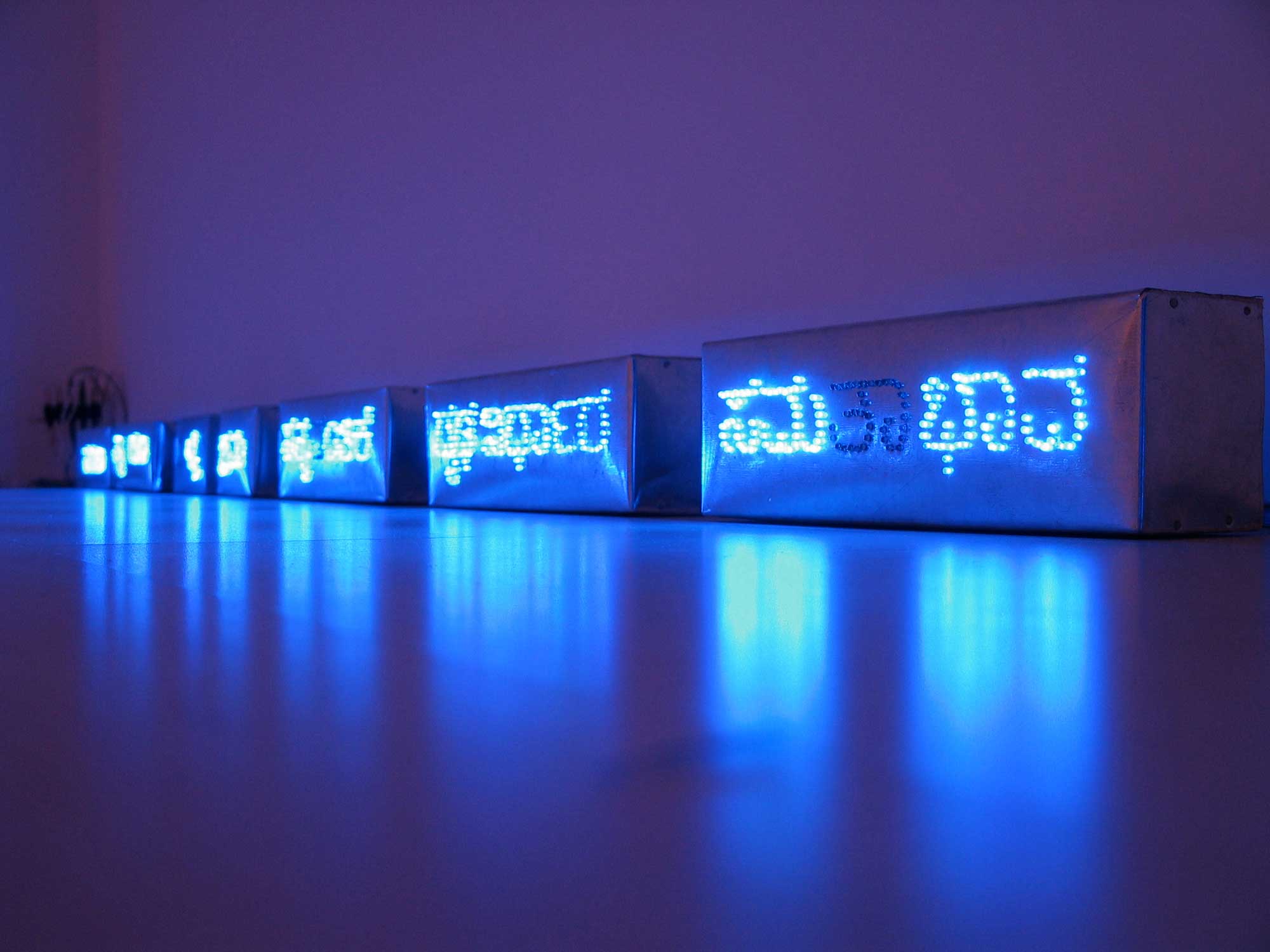

Hildegard Spielhofer, How to Do Art, 2004, A set of 7 words—Generosity, Renunciation, Effort, Patience, Determination, Honesty, and Equanimity—spelled in English and Kannada on 21 Tin boxes with LED lights, 30x10x10 cm each. Installation view, Gallery SKE, Bangalore, 2004. Image Courtesy: Artist

Further,

Haller’s attribution of a central position to Swiss artists in the global art

world’s center–periphery discourse may align with postcolonial narratives

seeking to decenter the privileged position of the ‘West’ in art institutions.

However, recent scholarship has revealed the complexity of the global art

scene, demonstrating that countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, and

Belgium often occupy peripheral positions.[19] It is indicative of the need to

rethink and redefine the notions of center and periphery in the global art

world. Haller’s decision to launch the website ‘Artists in Residence’

in 2001 can perhaps be seen as an acknowledgment of this issue. The website

aimed to make AiR programs in Switzerland more accessible to artists from

around the world, leveraging the power of the internet as a new medium for

worldwide communication. It offers tabulated information on how to apply to

independently organized residency spaces, together with comprehensive

information about living arrangements and funding. This information allowed

artists to directly contact the listed spaces, with the exchange relying on the

capital of friendly ties, and in so doing, it helped bypass the bureaucracy

often involved in institutionalized channels. In the wider ecosystem of art

databases on the internet, this website shares space with the Amsterdam-based TransArtists that began in 1997 with the aim to “make the

enormous worldwide residential art labyrinth accessible and usable to artists

through [their] website.” Together, the Aarau–Bangalore exchange as well as the

online databases reflect a growing desire among artists to come together,

self-organize, and bypass institutionalized channels in order to create new

models of artistic exchange and solidarity in a rapidly globalizing world. At

the same time, political theorists continue to critically examine precarious

labor in a capitalist economy using the notion of “affect,”[20] while also forwarding notions of

agonism and dissensus to reveal the hegemonic functions of dialogue and

consensus in modern democracy.[21] It may be worth reflecting on how

these ideas can be applied to the art world, and what implications they might

have for artist-led networking and alternative spaces.

[1] ‘Willkommen Bei Der Städtekonferenz Kultur’, Städtekonferenz Kultur (Website), Accessed 7 May 2023, https://skk-cvc.ch/#:~:text=Die%20St%C3%A4dtekonferenz%20Kultur%20(SKK)%20ist,Kulturdelegierten%20aus%2033%20Schweizer%20St%C3%A4dten.

[2] The term Genossenschaft translates to co-operative. Housing co-operatives have been in existence in Switzerland since as early as the mid-nineteenth century, when industrialization led to rampant migration from rural areas to cities, thus creating a housing shortage. In the co-operative model, several people combine their financial means, often with financial backing by the state, allowing them to construct apartments at a lower cost and lease them to one another at the cost price, eliminating the need for profit-making. Haller’s first venture with the housing co-operative model was in the late 1970s when, together with a group of people, they bought and renovated a house in the municipality of Rupperswil in the canton of Aargau. Having been acquainted with this form of association, he was later able to form a 450-member co-operative in the form of the Krone Genossenschaft. Today, the Krone Genossenschaft is owned and operated by a different set of people, after the original co-operative, under a new presidency, went bankrupt and sold the house in 2014. The residency hosted by the Arbeitsgruppe Gästeatelier Krone continues to operate from this building, with the rent being borne by the City of Aarau.

[3] Personal interview, Wenzel A. Haller, 6 December 2022, Aarau, Switzerland.

[4] In the 1970s, Rindlisbacher became the secretary of the Swiss Film Center and later established a cultural liaison office between Switzerland and North Africa in Cairo. This office was taken over by Pro Helvetia in 1988, where Rindlisbacher became an employee. With her mediation, many Swiss artists were able to go to Cairo for residencies or artistic projects between 1988 and 1999.

See ‘Kulturvermittlerin Ursula Rindlisbacher Gestorben’, Cinebulletin: Zeitschrift Der Schweizer Filmbranche (website), 7 August 2015, Accessed 30 April 2023, https://cinebulletin.ch/de_CH/news/kulturvermittlerin-ursula-rindlisbacher-gestorben.

[5] Ishita Chakraborty, ‘Sharing Is Caring’, Artfact: A Monthly News Journal by ArtsAcre, XV (March 2020), 6.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jhaveri, ‘Is It Still Referred to as “Going Abroad”?’, 13.

[8] Personal interview, Valentin Hauri, 25 November 2022, Zürich, Switzerland.

[9] Personal interview, Eva Mühletaler, 1 December 2022, Zürich, Switzerland.

[10] Personal interview, Sabine Trüb, 26 November 2022, Aarau, Switzerland.

[11] This did not pronounce the end of GAK’s exchange with India, as since 2013 there has been an ongoing collaboration between the GAK and artists from Kolkata, who have been recommending young Kolkata-based artists for the same six-month-long AiR program.

[12] Tushar Joag was in discussion with artists in Bangalore toward the joint development of “Art Raffles,” an “art lottery” in favor of refugees in Gujarat following the 2001 Gujarat earthquake.

[13] Ramsay Zarifeh, ‘Switzerland Offers Temporary Creative Home to Artists from Abroad’, Swissinfo.Ch, 20 September 2010, Accessed 7 May 2023, https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/switzerland-offers-temporary-creative-home-to-artists-from-abroad/2259886.

[14] ‘ History’, Bangalore Artist Residency One, Archived 3 August 2009 in the Internet Archive, Accessed 7 May 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20090803183001/http://www.bar1.org/history.html.

[15] Toward setting up their New Delhi office, Pro Helvetia had consulted Storz and Haller, given the GAK’s familiarity with the Indian landscape through their Bangalore network.

[16] Two artists from the respective grant-making periods of 2012 and 2013 became residents at BAR1, with their expenses being borne by the Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation. ‘BAR1, Bangalore’, Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation, Accessed 7 May 2023, https://www.inlaksfoundation.org/art/residencies-in-india/bar-1/.

[17] Shukla Sawant, ‘Instituting Artists’ Collectives: The Bangalore/Bengaluru Experiments with “Solidarity Economies”’, Transcultural Studies No. 1 (2012), https://heiup.uni-heidelberg.de/journals/index.php/transcultural/article/view/9275, Accessed 10 April 2023, unpaginated.

[18] Letter from W. A. Haller, on behalf of Gästeatelier Krone Aarau, to Visual Arts Department, Aargauer Kuratorium, 1999. Personal Archive of Wenzel. A. Haller, Aarau, Switzerland.

[19] See Pascal Gielen, ‘Art Politics in a Globalizing World’, in The Murmuring of the Artistic Multitude: Global Art, Memory and Post-Fordism, Antennae (Amsterdam: New York: Valiz, 2010), 14–20.

[20] Michael Hardt, “ Affective Labor.” Boundary 2 26, No. 2 (1999): 89–100.

[21] See Juan Meneses, ‘Introduction: Resisting Dialogue’ in Resisting Dialogue: Modern Fiction and the Future of Dissent (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

Shramona Maiti completed her MPhil in Visual Studies in 2022, with a thesis titled “The Shaping of Participatory Art in Bangalore: Dialogue, Dissensus, and the City.” She was a researcher in residence at the Gästeatelier Krone (Aarau) during the months of November and December, 2022, focussing on their history of cultural exchange.

The author would like to thank Wenzel A. Haller, Wolfgang Bortlik, Chinar Shah, Valentin Hauri, Michael Omlin, Eva Mühlethaler, Hildegard Spielhofer, Sabine Trüb, Patrizia Jegher, Katrin Zuzakova, Sureshkumar Gopalreddy, Surekha, and C.F. John for their generous help at various stages of research for the essay.