There

is NO Public Space

ekta

Published on 30.09.2024

We want to roam the streets without being stopped

We want to love freely without being watched

We want to be intoxicated without the night curfew

We want to wander the streets without directions

We want to break the locks of the park gate

We want to drink chai after everyone’s gone to sleep

We want to sleep under the stars

We want to wake up feeling safe

Let’s meet there.

Where no one comes or goes.

-Imaginary User of Free Public Space-

Does such a place exist? Perhaps not. The city is not designed for people for whom these simple pleasures are systematically restricted. The use of a space is determined by how it is mediated—by light, architecture, aesthetics, social location, etc. Space, then, is defined by a moral code of what is allowed and not, who can use it and how, and when it opens and shuts, held intact by a casteist and patriarchal order of the State and its people. Our senses—how we smell, touch, see, taste, and hear—are invariably governed by these moral codes that shape peoples’ experiences in the city. Only some people can enjoy the breeze of the city, others cannot. From this point of view, it appears that there is no public space. If there is public space open to some and denied to others, it is not ‘public space’ any longer, but can be read as a process of gentrification and appropriation of public space. In this essay, I reflect on our work in public spaces at maraa, a media and arts collective in Bangalore, and the complex negotiations with different actors who have a stake in public space.

Screening of Blancanieves by Pablo Berger at Shalimar Bar and Restaurant, Bangalore.

Screening of Blancanieves by Pablo Berger at Shalimar Bar and Restaurant, Bangalore.Public

Space as a Protest Site

When maraa started its work in 2008, we saw visible infrastructural shifts across the city—like the construction of the metro rail, the drastic felling of trees, slum evictions, glass and concrete high-rises, and frothing lakes—and that the promise of a smart city came at a very high cost. We were forced to respond to shrinking public spaces in the city of Bangalore. We got to know the shadow lines of the city by working closely with directly affected communities, labor unions, marginalized communities, and members of civil society. We rarely encountered these voices in any advocacy efforts, city planning, and design meets or budget allocations for use of public space. This learning made us observe the stark difference between the reality and the imagination of public space in the city. It was evident that protests were becoming the crux of our work in public space.

In our early years at maraa, we saw public space as a commons, an oasis amidst all the chaos and flow of the city. We wanted to demonstrate the use of public space for the arts as a way of being free of restrictions, finding spaces outside art galleries, art institutions, and the art market, which are most often hegemonic, restrictive, and hierarchical structures. We wanted to break away from ideas of high art, where a set of people would standardize what qualifies as art, who could access art and who could not, and who could discuss artistic practice.

Relaa, a protest music collective performing at Samsa

Amphitheatre, October Jam 2014.

Relaa, a protest music collective performing at Samsa

Amphitheatre, October Jam 2014.In October 2008, along with other artists from different fields, we occupied parks, streets, chai shops, or abandoned buildings every Sunday of the month, to rehearse, perform, converse, play, and jam. Many people liked the idea, probably because there was no sense of authority that could block or censor free expression. It became a safe space to share ideas without judgment or fear of meeting a particular standard. This culminated into the October Jam, an organic effort of an unstructured group of people coming together to organize an arts festival in public spaces. The name marked the anniversary of our first meeting in a park. The Jam was open for artists to pick a public space to showcase their works and reimagine the public space and audience.

We chose contested public spaces, such as Shivajinagar Market, where street vendors were being evicted; Nanda Park, where the metro was being constructed; Ulsoor Market, where many people were being displaced because of forced illegal land acquisition for infrastructural projects; Cubbon Park bandstand or Samsa Amphitheatre, spaces that were usually reserved for classical upper caste programs, mostly in Kannada. To us, working in public spaces was about creating opportunities for different kinds of publics to come together, even if only temporarily. Our interventions had a guerrilla nature, which made us realize the potential risk associated with certain forms of assertions.

In one of the October Jams, ‘Tightrope’, we created a kind of circus around the contradictions and ambiguities of Bangalore city through different artistic expressions in a public ground in Indiranagar. We invited Resident Welfare Association (RWA) members, our friends, artists, and the general public for the three-day festival. Indiranagar is one of the oldest areas of Bangalore and is known to have been occupied by wealthy old-timers. Today, it is one of the busiest areas in the city, also home to restaurants, pubs, and shopping centers. It was evident that the upper-class members of the RWA felt uncomfortable witnessing people from all walks of life occupying space that is otherwise reserved for people of the neighborhood. For those three days, though we could feel a lot of tension in the air, we strived to open the grounds to a large crowd that could otherwise never belong to such public space.

Tightrope, October Jam 2015, Bangalore

Tightrope, October Jam 2015, BangaloreAnother example of our occupation of public space is our use of the Samsa Amphitheatre or the Bandstand in Cubbon Park to subvert the usual programming that happens there, which is predominantly classical forms, in Mysore Kannada, as part of the cultural events. Rarely do you see any programs from other parts of Karnataka (North Karnataka, Hyderabad Karnataka, or Coastal Karnataka) or for that matter, any other folk forms or other language programs. Given that it is a public space, available at a nominal fee, we used it to program other kinds of concerts. When women workers claimed the stage, we could see that they had for one, forgotten about everyday household chores and were in fact having a blast, enjoying the lights and sounds of the tunes they wanted to dance to. This is often seen as a disturbance to the norm, as it goes against a fixed way of looking at space, people, and art.

Recently, we were asked to stop a program because there was no Kannada being used, and there was a refusal to accept that Dakhni is a language spoken in Karnataka. It is, in fact, a combination of Kannada and Urdu spoken widely across several areas in Bangalore and North Karnataka. This Kannadification in the city has heightened since 2014, and the idea of culture is controlled and manipulated by a few who protect their own caste and class interests. Any difference is seen as a threat, and it stems from an insecurity that audiences are getting diverted, and broadly, from a fear of a counterculture forming. Our work has thus been viewed with caution as we wish to create platforms for people who are denied this experience. We believe that people have a lot to express beyond their public identity, and those voices speak out loud, with pride and dignity. Over the years, we have become more vigilant in recognizing questions rooted in discrimination, and the insensitive gaze or ‘good intentions’ of the upper and middle classes. These ‘good intentions’ have often proved to be hostile and violent as we nudge the space that is called ‘public’.

Spaces for Diverse Publics

The Bangalore Pride March in 2008 stands out as an important instance of claiming public space—to literally “come out” and celebrate different sexual identities and to simultaneously advocate for repealing Section 377, that penalized homosexuality. At maraa, we made more than 80 hand-painted masks for the first Pride March. We have come a long way since then, and today the Pride March and the Bangalore Queer Film Festival, amongst others, have become much-awaited yearly events.

Some of our experiments have been ephemeral and our interactions with people were touch-and-go, mostly based on chance. In one of our interactions called ‘Storytelling on a Park Bench’ in 2009 for the Pride Month, close to 80 people gathered to hear and share stories. Friends and strangers participated to tell their own stories. To our surprise, people from all walks of life shared their stories, including a married policeman who spoke up after having observed us for quite some time; he narrated his story as an act of coming out. A sex worker opened up about her life in the city, about violent interactions with the police, and living with the threat of being in a public space for work. This format of storytelling invited strangers to share their experiences and somehow a sense of safe space prevailed for many who could not open up otherwise.

Our work around the metro construction in 2009 is another example of a show of resistance against the violent transformation of the city. Protests at the time focused on addressing issues such as alternate modes of transport, protecting the trees of Bangalore, and the displacement of people from their homes causing loss of jobs and discontinuation of education; however, we felt torn between participating in a protest rendered powerless by the State and a helplessness at not being able to do much. Hidden from public view, we ventured into makeshift tin-sheet colonies to meet migrant workers from across India who had come to Bangalore to build the metro rail. This was the birth of a hybrid film-based process called ‘Behind the Tin Sheets’. In collaboration with friends (Yashaswini Raghunandan and Paromita Dhar), we made films that reflected the inner worlds of migrant workers and a shared nostalgia for home. The workers didn’t appear as victims or heroes, but as figures with a visceral presence, appearing and disappearing in the everyday lives of residents in the city.

Even as we continued to engage with public spaces in different artistic ways, with the rising popularity of using arts in public spaces by a wide variety of artists and organizations (including corporate firms and cultural institutions who started using graffiti and mural art to enhance their ‘street’ credibility) we felt that the focus was getting to be more on the spectacle and less on the interaction with people who gathered as witnesses to the spectacle. The spectacle tends to draw attention to individualized bodies, uncritically celebrating a certain form of visibility which seeks to provoke the viewer. These provocations could be intended to produce a moral guilt in urban viewers when reflecting on their own lifestyles or about their perceptions of the city; they could also be about revealing a different side or aesthetic of the city that has not been mainstreamed.

An increasingly popular reason of using creative practices in public space was for social change, but invariably, we noticed that such interventions created more damage than good. Riddled with unfounded assumptions, this top-down approach ropes in people to rid their guilt of not doing enough, by doing something for a cause. For example, to create a litter-free, clean, eco-friendly city, several groups with support from the State mechanically went about sanitizing parks, streets, and neighborhoods, effectively rendering them suitable only for the upper- and middle classes of society. They ended up regulating the use of public space: locking parks after 6:00 pm, installing surveillance cameras and fitness equipment, directing people on the pathways they could use in the park, enforcing rules such as no lovers in the park, no street vendors, etc. Some people were thus forced to use public spaces within these codes and restrictions or were simply pushed out once they were labeled as miscreants, dangerous elements, thieves, and so on.

'Koogu', a solo performance by Anish Victor at Glasscrafters Studio's terrace and maraa's old office, Bangalore, 2011

'Koogu', a solo performance by Anish Victor at Glasscrafters Studio's terrace and maraa's old office, Bangalore, 2011

An Unequal Playing Ground

Though Bangalore hosts many densely populated settlements of lower-income or impoverished households, most remain hidden. The areas are associated with negative stereotypes of being unsafe, risky, dirty, dingy, congested, or polluted, which completely renders invisible a certain population of the city and often marks them out as criminals. In such settlements, diverse communities depend heavily on each other, given that basic civic amenities such as water, garbage disposal, electricity supply, or drinking water is either denied to them completely or is made available only in a tokenistic manner.

In early 2013, we witnessed how a large part of the Ejipura/Koramangala slum was demolished by the BBMP (the city’s Municipal Corporation) and more than 800 families forcibly evicted. Many were rendered homeless in spite of being legal residents of that area. They had previously been housed in Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) flats built in 1994, that had partially collapsed in 2007 due to substandard construction quality. Since then, all the EWS flats had been demolished, and the residents housed in makeshift shelters. Then, in 2013, the bulldozers barged in with no warning. Infants were sleeping, children were playing, women were cooking their evening meal, students were returning from college, and men were having their smoke break. And in a flash, pressure cookers were flying in the air, women were screeching, children awoke in shock, and people gathered around the bulldozers, enraged, trying to stop them with their bodies. Many watched their homes broken in front of their eyes. The sound was a fierce roar etched in the memory of a collective mass of people who were deemed powerless against the private interests sanctioned by the State. This settlement could be identified as the pulse of the city; people who live here work to keep the city ticking—they are migrants from everywhere in the country, and caste, religious, and ethnic minorities, essentially the subterranean mass of the city. This cruel and shocking experience affirmed whose interests were being protected in the city, and at what cost.

These extreme experiences made us realize that the discourse around art in public space neglects the structural hierarchy and violence embedded in spatial and social relations. Maarga, a Dalit organization working in the Koramangala Slum Cluster (KSC) for the last 30 years argues that many people living there for over 30-odd years still feel like temporary citizens, with no sense of security in the city. They have been striving for full citizenship as old migrants to the city, trying to get land that has been promised to them but remains elusive. In spite of having a voter card, Aadhaar card, ration card, and so on, and in spite of being legal residents of the EWS settlement, we were firsthand witnesses to how little their citizenship meant in reality. The only available public space for people who reside there is a shared common community hall, the use of which has been contested by several religious and political groups in the area. The main agenda of Maarga is to fight for an autonomous space, free of competing religious associations in the area, a safe and vibrant space that invites the youth to use their time creatively and productively rather than being diverted to drugs and suicide, which is often the case given their socio-economic conditions. Maarga was keen on creating a cultural shift for young adults and children by building a healthy environment through artistic practice. The intent was also to imagine a cultural center, a cultural hub in the middle of a densely populated residential cluster.

We took a hard look at our own use of phrases like ‘culture’, ‘cultural programming’, ‘cultural resistance’, etc. We could see the discursive role that arts played in the so-called public sphere, but we could also see that regardless of the spectacles produced by the arts in public spaces, as mentioned earlier, the material logic of the city remained unchanged. Our faith in constructing a shared public was thus weakening. We turned to imagining experiments in spaces for diverse publics, where hierarchies and differences could be diffused.

Occupying

Public Space

Over the years, we have seen various other groups face similar experiences to the residents of the Koramangala Slum Cluster. Powrakarmikas (street sweepers and cleaners of public spaces mostly employed by the Town Municipal Councils) have continuously protested for better wages, permanent jobs, better working conditions, and against practices of untouchability; garment workers, domestic workers, sex workers, street vendors—a significant population of the city—are denied their basic rights and dignity within the structures they operate in. In short, all the workers without whom the city would come to an immediate collapse are only visible to the city as long as they continue to perform their labor. The minute they come to the public space to assert their rights as citizens and as workers, they are either rendered invisible, harassed by the police, or vilified by the press as a nuisance.

When Forbidden Creatures Occupy a Park, an exhibit as part of the Public Space Festival organized by maraa, 2014

When Forbidden Creatures Occupy a Park, an exhibit as part of the Public Space Festival organized by maraa, 2014

On the other hand, we have also seen how dominant castes and upper classes have increasingly laid claim to public spaces as spaces of leisure (dog walking, jogging, etc.) and have lobbied behind the scenes to exclude those groups who use public spaces for work. To counter these claims, we created a space of sharing in Cubbon Park through the figure of the scarecrow in 2014, called ‘When Forbidden Creatures Occupy a Park’[1]. We worked with vendors, sex workers, migrant workers, and young lovers in the park to create scarecrows, a metaphor for all that is considered taboo, immoral, unsafe, and risky through the gaze of the upper castes/classes. The making of each scarecrow was accompanied by a story of how the park used to be, or a dream for the park as an open, inclusive space. The process culminated in an exhibition at Venkatappa Art Gallery, where the ‘scarecrows’, made from the materials of everyday life, ‘occupied’ a space for the arts, within a formal gallery structure.

In 2015, we also organized a walk around Shivajinagar, which was conceptualized in collaboration with the street vendors. Taking the form of a treasure hunt, participants were asked to interact with the vendors, where each clue contained stories of the marketplace and the vendors’ memories and experiences. In the same year, through a walk along the drains of the city, called the ‘Olfactory Chambers of Ward 55’, we explored the subterranean dynamics of the city by following a crucial but ignored aspect of urban life. The walk took people along the drains and past garbage collection centers, to highlight the deaths of manual scavengers, discuss debates between Gandhi and Ambedkar, and explore the caste question underlying the production and disposal of garbage in a city. The walk ended with visuals of a landfill, where a young girl questions the unchangeable nature of this intergenerational occupation in her community. If we follow each step in the collection of garbage until it lands up in landfills outside the city, we get a microcosm that, when scaled up, explains the Indian urban dynamic perfectly.

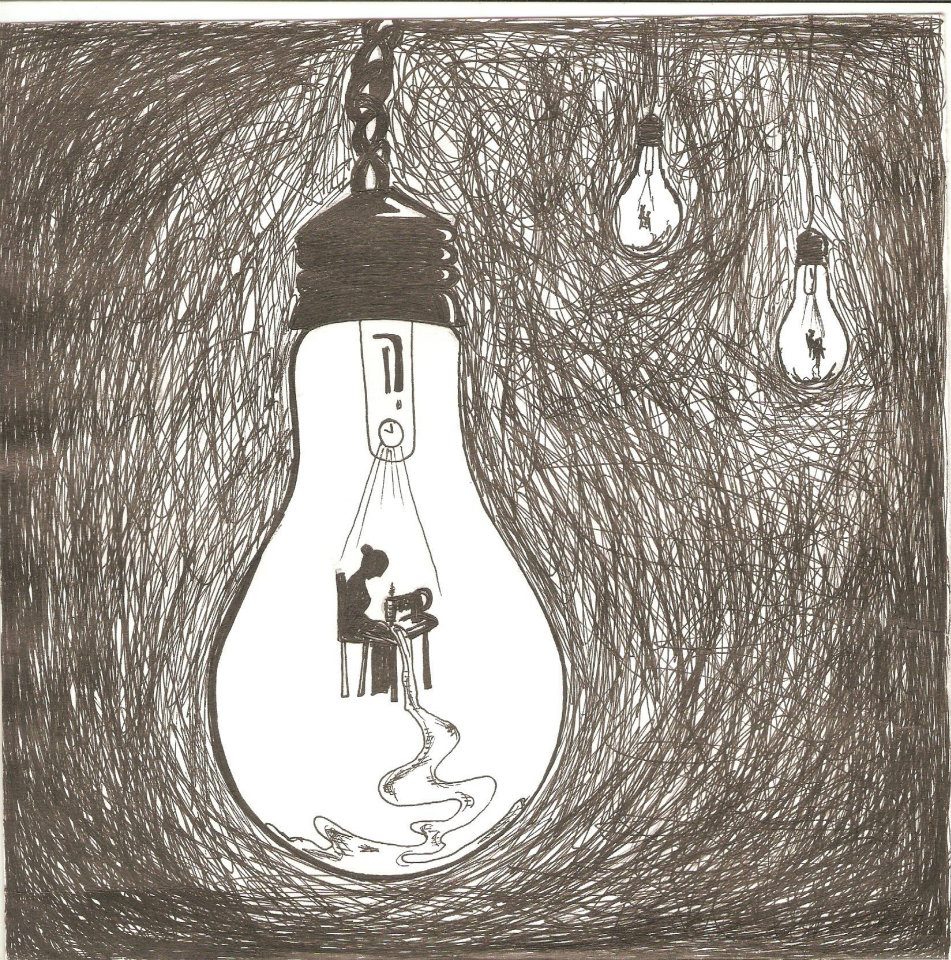

Illustration by Pallavi Chander, a response to the protest organized by garment workers against unjust working conditions

In 2014, when we worked on safety audits for working women in the city, we learnt that the concerns of upper- and middle-class women were radically different from those of working-class women. Middle- and upper-class interests were protected to keep ‘miscreants and dangerous people’ away. Public spaces had to be sanitized from a certain kind of public, which invited architectural-infrastructural changes and a swift gentrification of Bangalore. Who are these miscreants, thieves, and dangerous people? Our work took us back to rehabilitation sites where many of the ghettos of Bangalore are segregated by caste and religion. We worked with several unions to understand the complexities involved, especially with women workers who comprise a significant percentage of the population. For example, Bangalore has more than 600,000 garment workers who are part of the organized sector, most of them suffering horrendous working conditions. Their accounts of the city and their employers reveal a very bleak picture of ‘the public’ and public space. The exhibit titled 'Mallige' (Jasmine) was a collective account of garment workers in their domestic spaces with interviews that reflected their experiences inside the factory. ‘Mallige’ (Jasmine) was a collective account of garment workers on their everyday experience of life in the city, enmeshed with their desires for love, friendship, and respite.

Launch of Bevaru, Bangalore, 2017

Launch of Bevaru, Bangalore, 2017In 2017, we worked on an initiative called ‘Bevaru’, which means sweat, to bring out accounts of workers, especially the women workforce in the city; it was a bi-monthly newspaper published in Kannada, English, and Hindi that we distributed in public spaces. The writings were focused on the views, experiences, and ideas of workers. It moved away from simplistic victimization to address structural issues in the system that rendered them marginalized. We gathered accounts of gross injustice, inequality, and discrimination that were resisted by everyday protest, which does not always take the form of an organized political protest. Our decision to publish a broadsheet was born out of our frustration at how the media covers issues of the working class. To date, reportage on sex work is reduced to ‘flesh trade’. Any report on any kind of worker has been reduced to death counts and accidents, completely ignoring the fact that workers are the lifeline of the city. Further, when it comes to women workers, there is hardly any discourse apart from them being victims within their workspaces or protesting for their rights. We felt there was a need to bring out stories of women workers (powrakarmikas, domestic workers, sex workers, garment workers, etc.) in Bangalore. This included the question of what leisure means for women workers, if they occupy public space, and if so, what their ways of expressing themselves could be. Do they like to dance, sing, paint, write? Would they want to share it with others?

Further, we found that most accounts of workers tended to focus only on their identities at work, reducing them to their functionality. We wished to engage with workers outside their productivity, focusing on their dreams, aspirations, and desires. Outside of labor, can there be a space of leisure for workers who build the city? This led us to conceptualize a concert called ‘Purabiya Taan’ in 2016, featuring the renowned Bhojpuri singer Kalpana Patowary. Our invitation took the form of a love letter from the city to the worker. The invitation acknowledged their presence in the city and invited them to experience an evening away from the workplace or their colony. The idea was for them to feel a sense of love and respect from people who live in Bangalore. We distributed it to the migrant workers in labor colonies strewn across the city. The concert took place in Samsa Amphitheatre, usually used only for Kannada cultural events; this was also a way for the workers to take a different route and move away from their everyday paths within the city.

Prema Revathy, actor, activist, and educator performs the play ‘Sudailaiamma’ in Paparajanahalli, for members of the Domestic Workers Union, Bangalore, 2019

Prema Revathy, actor, activist, and educator performs the play ‘Sudailaiamma’ in Paparajanahalli, for members of the Domestic Workers Union, Bangalore, 2019There is NO Public Space

Over the years of learning from lived experiences, our work has moved considerably away from public space, because our work was no longer about an abstract public in an abstract public space. We zeroed in on building our work as longer processes, where we internally had to clarify to ourselves why, where, and to whom we were addressing our work. What is their involvement in the creation of it? We discussed the issues around politics of representation, where we wondered how much we were embodied in an experience when telling stories of others. Also bearing in mind the stereotypical representation by mainstream media, we were keen to not just show the intersectionality of exploitation, domination, discrimination, and violence, but also represent the creativity and agency of thousands of workers who engage in their struggles with dignity and hope. Here, the arts have immense potential—on the one hand, in challenging the aesthetics of gaze, which marks certain populations with stigma and discrimination, by celebrating their lives and experiences; second, in enabling self-representation within these communities, so that they can tell their stories on their own terms. This also challenges the upper caste/class hegemony within the arts sector, that decides the boundaries between art and experience, between labor and culture, between materiality and aesthetics. We aim to break the notions of who is the artist, who can make art, whose art is worth seeing, and what is the marketspace that governs these questions.

The COVID-19 pandemic made the absence of public spaces even more strongly apparent to us. Everywhere around us we witnessed public spaces shrinking to keep the dangerous ‘Other’ outside. Strict rules, regulations, and restrictions in the name of social distancing served some, while rendering many others vulnerable and strapped for resources. As we engaged with migrant workers, we learnt that the State has a role in engineering sharp divisions within the body politic. They literally clamped down on their mobility, freedom of expression, and dignity. The only space for uncompromised expression through TikTok was also banned by the government.

The private sector also has a role in protecting their interests and profit motives regardless of the social consequences. The space for resistance seemed unorganized, chaotic, and sharply divided along ideological differences. The CAA and NRC protests brought everyone together, but only briefly. The post-pandemic political crisis has led us to introspect further on the work we are doing, how we are going about it, why we want to do this work, with whom, and to what end.

Given the fluidity of the concept of ‘public’, given that it is always made in flux, we have come to realize that space is incidental. A given place can always become a space based on who uses it, how it is used, and what it is used for. Therefore, for anyone who wants to work productively with the idea of public and public space, paying rigorous attention to the people who use that space should be the priority. Here, the metaphor of occupation is significant, an aggressive metaphor used most often in war situations. In this context, occupation signifies taking up something that has been denied. For those who have been denied, access provides the opportunity to assert the self in a way that is historically significant.

Reimagining our Role

In 2021, for ‘Truth Dream’, we worked closely with the senior trans community of the city, who were keen on becoming the fantasy figures they had dreamt of in their childhoods. They wanted us to work on a photo exhibit, allowing them to enter their dream worlds with no compromise on the backdrop, the make-up, the costumes, and the music. The attempt was to challenge the notions of beauty, aging, and fantasy. We shot black-and-white and color images as imagined by our collaborators. In these images, each person performed, realized, and became their fantasies, momentarily taking over their own visual representation that freed them from their lived experiences in Bangalore, that had rendered them as stereotypes that they had been resisting over the years individually and as a community. It was hauntingly surreal to see everyone come alive, breaking myths about the transgender community and questioning the space for better opportunities as legal citizens of the country. The exhibition portrayed beauty and horror in the same breath, without shying away from either.

Truth Dream, a live showcase at the Bangalore International Centre, 2021

We have turned to artists who raise questions on identity, discrimination, and injustice. We have learnt about, featured, and worked with artists like Pasha Bhai, Jangama Collective, Neelavarana, Blue Material, and Queer Poets Collective. These collectives are not just fighting issues of representation, but are questioning the fundamental principles of culture, economy, labor, gender, and so on. Jangama’s work process contemporizes the relevance of Dalit literature that is on the brink of being lost, forgotten, and sidelined, in the present context. Through their plays, they showcase the imagination of the connections between the socio-spiritual world that people inhabit. Neelavarna, an Ambedkarite artists forum dedicated to promoting Bahujan artists in Kannada, marks a new wave in cinema, working to break the hegemonic representation of people from the margins and subverting the representation of the Dalit community in cinema. It provides a glimpse into playful ways to break down a caste-based society through conversation, storytelling, and absurdity. Likewise, Blue Material’s turn to comedy breaks the very idea of marginalized voices always having to be identified with a particular tone and story. Using profanity and humor, they point out the undisputed differences and prejudices in society. maraa works in collaboration with these initiatives to build smaller collectives, organize festivals, raise funds, and also protest when necessary. Now, the space does not matter; it is what we do in the space that does. It can be anywhere—in a private, public, or virtual realm.

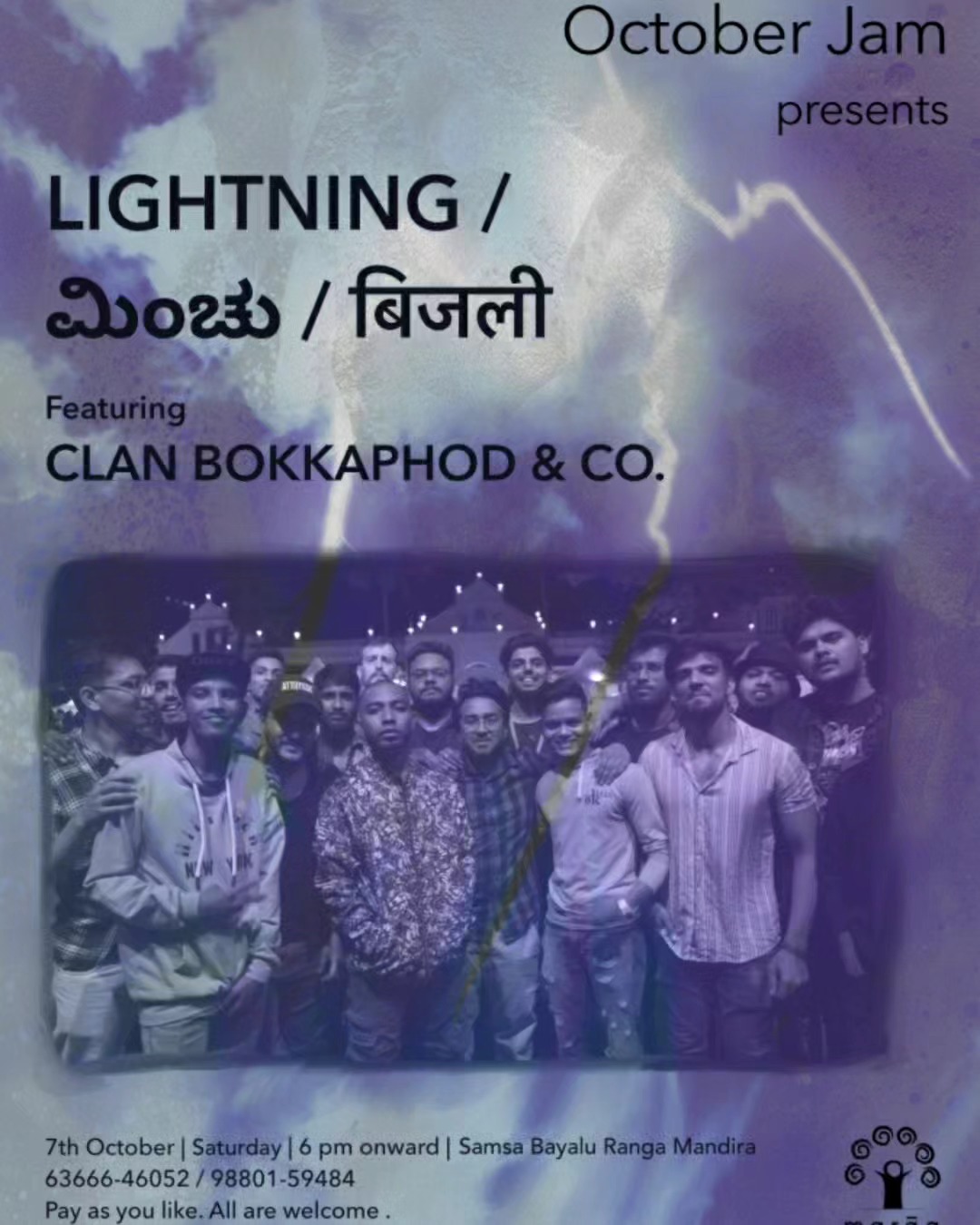

Lightning, October Jam 2023, Bangalore

Lightning, October Jam 2023, Bangalore The tension created by the political environment has only provided an elasticity of free speech and expression, which by no measure can be categorized as any particular form. Our job is to listen, work through the ruptures, and foreground voices to amplify the freedom they have already sought independently—indignant, free-spirited, conscious voices that can leak out and tear through the illusion of public space in the city. Much like a Leonard Cohen song, there is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.

[1] https://thewire.in/urban/cubbon-park-bengaluru

ekta co-founded maraa, a media and arts collective in Bangalore in 2008. She works there as a researcher, facilitator, and curator around issues of gender, labor, and caste in rural and urban contexts. She has been making films around labor, migration and cities since 2009. Her recent films ‘Birha’ and ‘Gumnaam Din’ is about separation and longing in the context of migration. She is currently co-working on a pedagogy of arts practice as catharsis and curating festivals around cultural resistance.