Placemaking without Borders (Part 1)

Framing the Artistic Exchange between Bangalore and Aarau amid

India’s Post-liberalization Internationalism

Shramona Maiti

Published on 12.06.2023

The

1990s in India is often signposted as the decade that began to host a notable

influx of foreign individuals—some artists, some entrepreneurs, and some

investors, who founded galleries and art spaces as they leveraged the new

openings offered by economic liberalization. American artist Peter Nagy and his

setting up of the gallery Nature Morte in New Delhi in 1997, for instance, stands as an iconic

testament of that period. While the intersection of internationalism and Indian

art is not a new phenomenon, the period of economic liberalization in India becomes important for having brought

into regular discussion the dominance of nation-centrism in the context of both

art worlds and artmaking. This prompted a re-evaluation of the relevance of nation-centrism in the new

globalized art world, when the very nomadic movement of artists across the

globe became apposite to the cross-fertilizing of new pathways. While individuals

continue to navigate nation-imposed identities such as gender, race,

nationality, ethnicity, and cultural background, the mobility of artists

facilitated the exchange of ideas, presenting possibilities to challenge and reshape

prevailing notions of identity. It is against this backdrop that the year 1997

also saw a group of artists in Bangalore[1] entering into an exchange program

with Aarau, a small town and the capital of Switzerland’s northern canton of

Aargau, that took two forms. First, artists from Bangalore traveled to Aarau

for six-month residencies, and later a residency was established in

Malleswaram, Bangalore, hosting artists from Palestine and Switzerland. Written

in two parts, this article aims to contextualize this exchange within the

broader global phenomenon of the post-90s “art worlds” and the new

internationalism that marked India’s post-liberalization era.

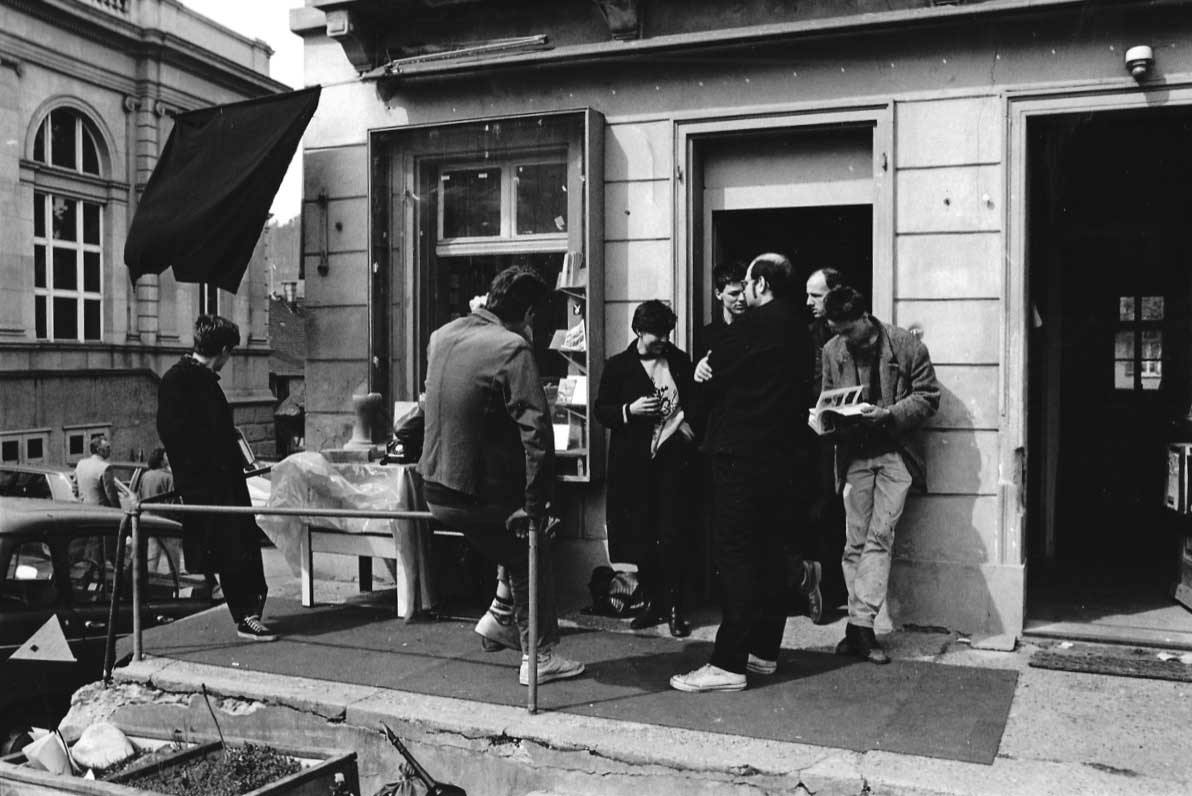

Gathering of artists in the studio at Kronengasse, Aarau in 2005, on the

occasion of the ten-year anniversary of the Arbeitsgruppe Gästeatelier Krone’s

(GAK) artist-in-residence programme. From the archives of Gästatelier Krone 2005. The photograph appeared in Isabel Zürcher, ‘Gästeatelier Krone — Willkommenskultur Seit 25 Jahren’, Kunstbulletin 12 (2020).

The first part lays the framework to situate the Aarau–Bangalore exchange, beginning with an exploration of the complex dynamics of internationalism in the landscape of Indian art post independence. It then argues that the factors driving the emergence of new internationalism extend beyond economic liberalization and should be considered from a broader perspective. To do this, the essay examines the transformative period of the “long 1980s,” focusing on specific moments in the histories of Bangalore and Aarau, as it seeks to imagine possibilities for cultural coevalness between these historically distinct regions. It concludes by discussing the idea of contemporary art and its pivotal role in fostering cultural exchange. The second part of the article builds upon this foundation and presents a detailed account of the Aarau–Bangalore exchange program, delving into its origin, development, and impact.

Together, the two articles highlight the significance of the Aarau–Bangalore artistic exchange within the critical history of global art, emphasizing how artist-led placemaking played a role in overcoming cultural barriers in the post-90s art world. It thus aims to offer insights into the complex interplay of ideologies, self-organization, and the making of a global art space.

HISTORICIZING INTERNATIONALISM IN POST-INDEPENDENCE INDIA

When the Khoj artists’ association started in New Delhi, one of the main aims behind its workshop model was to establish Asia–Asia dialogues, bringing into contact historically divided pathways that were not connected before.[2] This came as a critique of the idea of internationalism operative in India that tended to privilege the West. While scholars have praised the far-reaching possibilities of artistic mobility in Nehruvian modernizing projects, it is worth noting that the emergence of the West as a looming center was a gradual and ongoing process. These processes often revealed such tendencies, a bureaucratic logic, and the contours of a nation-centric discourse when the most visible form of internationalism arrived as “exchanges with Britain […] facilitated by Commonwealth, British Council and Inlaks scholarships, and with the United States by Fulbright scholarships.”[3] International diplomacy had been a determining force in realizing artistic mobility and facilitating cross-border aesthetic exchanges, such that the ambit of diplomacy was not limited to being defined as a brute force exercised by bureaucrats sitting in offices and making decisions that resulted in cultural exchanges like the Festival of India.[4] Encounters with international diplomacy was very much present even in seminal cultural occurrences initiated by individuals, such as Pupul Jayakar organizing a craft exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, in 1955. On one hand, Jayakar is remembered for her independent commitment to craft activism, and the exhibition at MoMA was crucial in signaling a paradigm shift in the reception of Indian visual culture in North America—from the aura of Orientalism that produced exotic work with limited marketability to being recognized as a craft production that could easily cater to the growing American household market. On the other hand, the exhibition also served as a pretext to solicit support from the Ford Foundation in planning for the development of a design industry in India.[5] This trajectory continued through the arrival of the American design duo Charles and Ray Eames in India and their survey of the needs for a prospective Indian design industry, resulting in the directives for setting up design institutes in India.

While such developments forwarded Nehru’s idea of internationalism and encouraged foreign travel, they were assisted by the larger logic of nation-building, which was significant in establishing friendly ties between India and North America, and in familiarizing a route for back-and-forth exchange. The same route continued even in instances which had no dealings with international diplomacy but avowedly served private interests, such as the stays of foreign artists hosted at Villa de Madame Manorama Sarabhai from the 1950s through the 1980s and early 1990s. With the Sarabhais being notable patrons of modern architecture, and bringing to India the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn, the artists they hosted, too, were of known repute, such as Isamu Noguchi, Alexander Calder, and John Baldessari, to name a few, as detailed in Shanay Jhaveri’s foreword to the book on Western artists in India inspiring art and design.[6] One may then ask if nation-centrism is loosely operative when the nation declares its culture, thereby influencing the paradigm of visibility and recognition, and subsequently tying the identity and work of artists to this recognition; Jhaveri remarks on Sarabhai’s possessions as being “the first private Indian collection of modern American art.”[7] Even as the author claims that the Sarabhai instance demonstrates “assured active agency, separate from the state,”[8] the unconventionality of such internationalism is oftentimes cloaked in ambivalence when intersecting with the interests of state-bodies; the MoMA, for one, held the exhibition “Made in India” in 1985, featuring exhibits from the Sarabhai collection, thereby continuing to understand cultural exchange from the determinations of a physical collection endowed with assured value by the adjudicating Western institutions and their discourse.

On the flipside, another form of internationalism, arriving as transnationalism, critiques nation-centrism and its exchange with capital in the narrative of Indian modernism. Through his cartoons, the artist Chittaprosad is known to have expressed his distaste for Prime Minister Nehru’s diplomatic ties with the Americans and their capitalist culture.[9] Interestingly, Chittaprosad’s socialist outlook and aesthetic preference for folk and popular art led to his friendly ties with Czechoslovakia, as an example of “transnational solidarity.”[10] This was based on shared ideas of equality and justice, and a belief in the universal exchangeability of the socialist cause carried across cultures of the Second and the Third Worlds. Without having set foot on the land, the artist found reception in Czechoslovakia and support for his work by being featured in their journals, while he continued to be marginalized in the discourse of Indian high modernism. However, Chittaprosad resisted attempts to market his art in India, denouncing art as a commodity and being suspicious of artists who produced art for money.[11] This form of transnationalism challenges an internationalism that safeguards the interests of private capital in exchange with mainstream national politics. It even arrives as a separate channel from the international ties maintained by India with Czechoslovakia, following India’s non-aligned foreign policy that included building alliances with other non-aligned nations such as Czechoslovakia.

Finally, the idea of the West in India may largely refer to North America, Great Britain, and also Western Europe, serving as a distinct ideological sphere as the Western capitalist bloc in tension with the Eastern communist bloc during the Cold War period. But these affiliations did not remain fixed, as with the fall of communism in 1989, and the resulting balkanization of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, countries of the former East like the Czech Republic and Slovakia began to shift toward a more Western-oriented foreign policy, and after the split, became members of various Western organizations, such as the European Union and NATO. While the idea of the nation and its distinct borders weigh in heavily in these ways of mapping the world and global relations, we also have historical instances like the one above with a transnational solidarity. It shows how some global networks—with cultural exchange at their heart—were born by being cognizant of a nation-imposed idea of culture and consciously subverting this paradigm by establishing newer platforms to facilitate dialogue and exchange. Even in the recent cultural initiatives undertaken by the Goethe Institut in India, and to a lesser extent the Alliance Française, there have been considerable efforts to identify cultural exchange through spaces that lie outside, and even operate against, the framework of the nation. One such way has been to focus on the dynamics of the city and collaborating with artists involved in the establishment of alternative spaces.[12] Thus, noting the existence of a logic of internationalism that may still privilege Western institutions and discourses, limiting the scope of its internationalism, it is important to distinguish the West as a location and the West as a discourse. In this sense, subversive networks that are situated in the “geographical” West can be thought of as being critical of the West as a discourse, even as they continue to fall under national demarcations. The cultural exchange between Aarau and Bangalore, with Aarau being a part of Switzerland, I contend, can be seen as belonging to such a subversive matrix.

GLOBAL CONVERGENCES: PLACEMAKING AND THE LONG 1980s

Poster for the book Kleinstadt

Rebellion at Ochsengässli, Aarau, as one among a series of the same poster

appearing at various public spaces in the city. Photo: Wenzel A. Haller

Poster for the book Kleinstadt

Rebellion at Ochsengässli, Aarau, as one among a series of the same poster

appearing at various public spaces in the city. Photo: Wenzel A. Haller

The exchange between Aarau and Bangalore began as an artist-in-residence (AiR) program held out of a studio apartment in Aarau in 1997. On the Swiss side, the development was more incidental than programmatic. Wenzel A. Haller, practicing as a ceramist in Aarau for two decades through the 1970s and 1980s, ideated the need for an AiR program in Aarau. It was Christoph Storz, fellow artist and former resident of Aarau, who informed Haller about artists actively involved in producing contemporary art in Bangalore. In fact, these artists did not enjoy visibility in the art scene in India, which was then being recognized as an emerging global market for art. As cities became art centers and signaled a specific art market with their booming galleries, the art scene of Bangalore did not truly partake of this economy. This is when Mumbai and Delhi were presenting globally recognized and highly developed art markets, such that, from time to time, they were susceptible to criticism for promoting artworks deemed “alternative,” while “being tailor-made for transaction as peripatetic objects with signature value in the ‘big top’ of the art fair.”[13] In the late 1990s, Storz’s knowledge of Bangalore’s art scene came from having recently relocated to the city, joining his partner and artist Sheela Gowda, whom he had met at a residency in Paris. Haller’s readiness to connect with artists from Bangalore was, therefore, not driven by a desire to bank on readily available cultural and symbolic capital; it rather speaks of relying on pure happenstance, motivated merely by a curiosity about what contemporary art from this city in India could look like.

At the same time, the cultural placement of this exchange, happening in the late 1990s, should not be seen exclusively against the background of the great economic changes brought in by economic liberalization. It is also in line with the period that is being understood more and more as the long 1980s, witnessing “changing relationship between ideologies, governments, and their publics, the effects of which have come to shape the contemporary condition.”[14] With a rough timeline drawn from 1975 to 1995, a hallmark of this period is the existence of individual desires for alternative forms of self-organization and staging art as activism, taking it to the streets, but also through “words, images, objects, and actions.”[15] In this regard, the histories of Aarau, Bangalore, and its young artists, meet at a shared synchrony. Throughout the 1980s, Haller was a prominent figure in Aarau, involved as a subversive thinker and organizer of social spaces that interrupted the town’s gentrification drive. He began several initiatives such as shared housing spaces and co-founded cultural alternatives with fellow anarchist Wolfgang Bortlik.[16] This included the Alpenzeigernewspaper, which reported on Aarau’s counterculture movements and served as a counterbalance to mainstream media, and Das goldene Kalb, a bookstore-cum-art gallery.[17] All this was part of the youth revolt that had gripped Aarau in the form of a “Kleinstadt Rebellion,” translating roughly as “small-town rebellion,” coinciding with anti-nuclear protests, the rise of punk culture, and the squatter movement.[18] It ran parallel to the larger cultural landscape of Switzerland in the 1980s, when youth rebellions challenged the existing institutional fabric of the city by demanding spaces that then became “politicised places(s) for counter culture.”[19]

Pages from the periodical “Alpenzeiger,” started by Wenzel A. Haller, Wolfgang Bortlik, Emanuel and Mary Claire Martinoli among others, running between the years 1975-1999. Image courtesy: Wolfgang Bortlik

Newspaper clipping of Wolfgang Bortlik (center) and Wenzel A. Haller (right) at a May Day demonstration in Aarau, Freie Aargauer, 1977. Image courtesy: Wolfgang Bortlik

India, on the other hand, was reeling from the effects of the Emergency (1975-77) in the 1970s, when the threat to democracy saw widespread student protests and autonomous women’s movements voicing resistance against state-sanctioned inequalities. In this political landscape, Bangalore emerged as a focal point for counter-institutional developments, birthing collectives that framed themselves as “alternative” institutes—“those not entrenched in an institutionalized and universal notion of equality.”[20] Beginning with the Center for Informal Education and Development Studies (CIEDS) in 1975, the scene proliferated with others such as the Bangalore Film Society coming up in 1977, and the feminist collective Vimochana Forum for Human Rights in 1979. In Bangalore, specifically, the 1980s saw the migration of (chiefly) men from Iran, Jordan, Palestine, and other West Asian regions, as they were “fleeing repressive regimes in their own countries or seeking moments of respite from military duty, war, or marriage.”[21] There was also an influx of refugees from Bangladesh following the Bangla liberation war of 1971. This came at a time when the Indian state recognized only political victims as “refugees” and excluded gendered violence, making it difficult for others such as Bangladeshi women, who were pregnant after rape during the Bangla liberation war of 1971, to seek refugee status.[22] Vimochana, thus, responded by setting up a public forum to address the issue of “human rights violation of women within the home and outside,” in the context of larger structures of violence and power.[23] On the other hand, CIEDS, a multifarious collective, was involved with “environment and ecology, housing rights, film and communications, art and culture, peace and militarisation,”[24] while also birthing offshoots through personal initiatives by its members.[25] Both Vimochana and the Bangalore Film Society (BFS) had emerged out of CIEDS, initiated by human rights and women’s rights activist Corinne Kumar. The BFS was formed during the film society movement in Bengaluru, to create an open space for “vigorous political debate and provocative convenings” as they screened feature films and documentaries, while not shying away from other experimental

formats.[26] Each were committed as being spaces critiquing exclusionist policies of the state, either by providing legal and social infrastructure for those marginalized by the state, or by being spaces for dialogue and debate, thereby involving themselves in the continuous process of expanding the idea of culture.

Both the Swiss countercultural scene and the rise of autonomous collectives in Bangalore trace an itinerary of movements evolving out of the disillusionment in classical politics,[27] when local politics emerged as alternatives to state authority. Thus, as the trajectory of Aarau intersects with that of Bangalore in the late 1990s, this cultural backdrop of the long 1980s arrives as a moment of global entanglement, presenting possibilities of cultural coevalness through their shared encounters with crisis in the urban space. Placemaking, then, resulting out of this dynamic, can be seen to emerge from thinking beyond the border, where the border had been impeding the evolution of culture—be it local or global.

CONTEMPORARY ART AND NEW INTERNATIONALISM: TRANSFORMING CULTURAL EXCHANGE

Returning to the 1990s, much has been said about the correlation between the decade being a time of rising fundamentalist forces in India and also the rise of installation and video art. Cited in this narrative is the emergence of a networked space of the “secular” in the cultural sphere, cross-fertilized by critical collectives of artists and activists. Here, the Delhi-based SAHMAT collective had been at the helm, with visual art practitioners having taken up interdisciplinary approaches to question traditional modes of spectatorship. The best-remembered example is Vivan Sundaram’s Memorial, exhibited at the gallery of All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society in December of 1993, which Geeta Kapur often cites as being the first work of installation art in India. In Bangalore, too, an art installation was realized collaboratively earlier in 1993. Titled “Cultural Spiral,” this project was initiated when Saraswathy Ganapathy, a cultural activist and partner of the late Kannada playwright Girish Karnad, contacted Bangalore-based artist C.F. John to help mount a show arranged by SAHMAT. John was already working with Visthaar, another autonomous collective, and had created artworks in response to communal tensions that had gripped the city in 1992; he then involved Sheela Gowda to discuss collaborative possibilities for the show. She brought in Hyderabad-based art critic Rasna Bhushan and two young artists, Raghavendra Rao and Surekha, to help execute the work.[28] This was a time when presumed ideas of culture and tradition were being debated and discussed in literary circles, as artists were becoming increasingly suspicious of the iconic efficacy of visuals and how they lend easily to a statist idea of culture. In artmaking, a self-reflective paradigm could be achieved by allowing the integration of the position of the viewer within the artwork, posing them as “witness” to the crisis in democracy. This took shape best in the form of installation and site-specific art. It was also the chosen mode to exhibit “Cultural Spiral,” as it became a spiral maze featuring painted visuals on makeshift walls of plastic sheet, allowing audiences to physically immerse themselves in the experience. Through the 1990s, Bangalore emerged as a hub for art that resisted the monopolization of cultural thinking, engaging with the complex realities of contemporary urban life. A notable example of an artist from the time is Umesh Madanahalli, whose site-specific Earth Works in 1996 tackled issues of urbanization, globalization, and environmental degradation at a time when Bangalore was undergoing rapid transformation into India’s Silicon Valley, attracting large volumes of migration and causing a shift in the city’s socioeconomic fabric. Later, in 1997, Raghavendra Rao became the first artist from Bangalore to participate in the Aarau exchange, followed by Surekha in 1999.

Das Goldene Kalb, or The Golden Calf, a small store started by Wenzel A.

Haller and Wolfgang Bortlik, running between the years 1982 and 1984 in

Schlossplatz (Aarau), and operating as a meeting place for youth while also

hosting exhibitions, readings, film screenings, and small concerts.

Following its demolition, the store relocated to Ziegelrain 4 (Aarau) in 1985,

functioning as a bookstore and art gallery, with a new collective overseeing

its operations from 1992 to 2012. Image courtesy: Wolfgang Bortlik

Das Goldene Kalb, or The Golden Calf, a small store started by Wenzel A.

Haller and Wolfgang Bortlik, running between the years 1982 and 1984 in

Schlossplatz (Aarau), and operating as a meeting place for youth while also

hosting exhibitions, readings, film screenings, and small concerts.

Following its demolition, the store relocated to Ziegelrain 4 (Aarau) in 1985,

functioning as a bookstore and art gallery, with a new collective overseeing

its operations from 1992 to 2012. Image courtesy: Wolfgang Bortlik

Artists installing the work Cultural

Spiral at Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. Participating

Artists: Sheila Gowda, Rasna Bushan, Raghavendra Rao, Om Prakash, Ravishankar

Rao, P.C. Stephan, Surekha, Sudharsan, Somasekara, Dhanaraj Keezhara, and C.F.

John. Image courtesy: C.F. John

Artists installing the work Cultural

Spiral at Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. Participating

Artists: Sheila Gowda, Rasna Bushan, Raghavendra Rao, Om Prakash, Ravishankar

Rao, P.C. Stephan, Surekha, Sudharsan, Somasekara, Dhanaraj Keezhara, and C.F.

John. Image courtesy: C.F. John

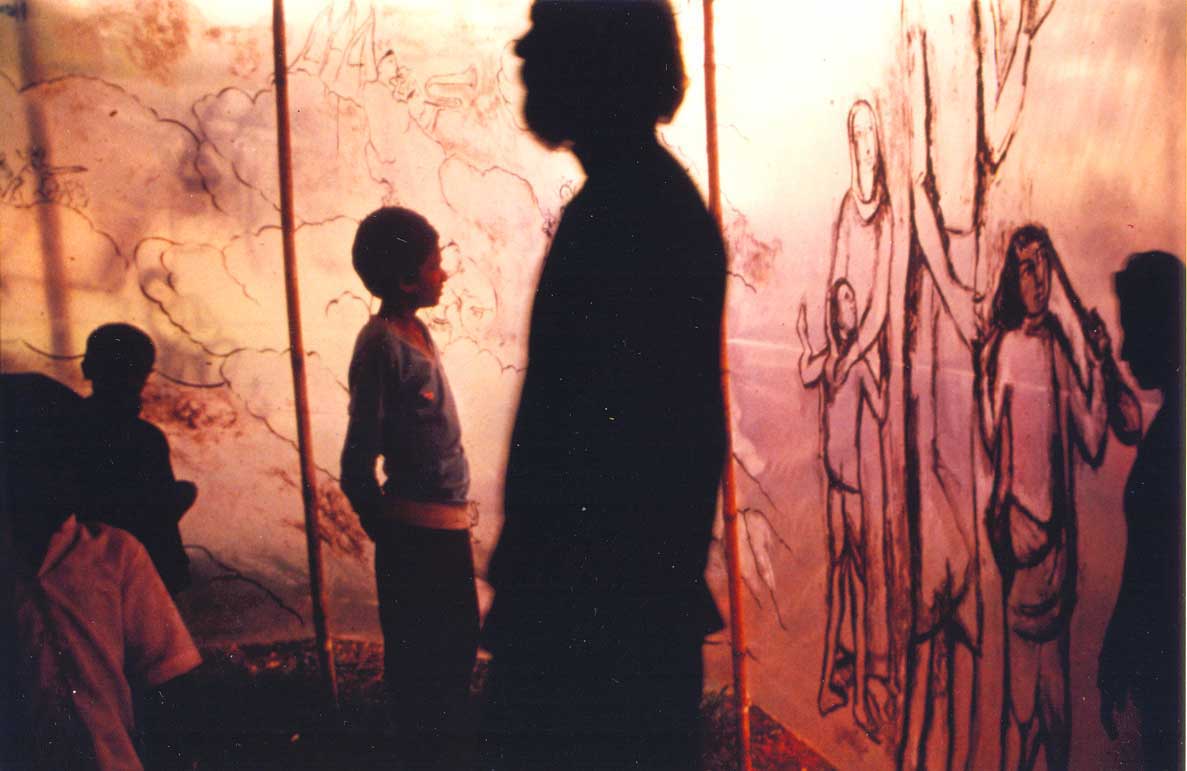

Audience interacting with the installation Cultural Spiral at Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. A

40ft x 40ft x 6ft installation was arranged as a spiral maze with transparent

plastic sheets, bamboo poles, and centrally placed parallel mirrors at the

heart of the maze. The plastic sheets featured visuals and text from historical

counter-cultural movements in India, reproduced in English and Kannada in

printing ink. Image courtesy: C.F. John

Audience interacting with the installation Cultural Spiral at Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. A

40ft x 40ft x 6ft installation was arranged as a spiral maze with transparent

plastic sheets, bamboo poles, and centrally placed parallel mirrors at the

heart of the maze. The plastic sheets featured visuals and text from historical

counter-cultural movements in India, reproduced in English and Kannada in

printing ink. Image courtesy: C.F. John

Participating artists at the installation Cultural Spiral, Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. In the image at the center, artist Ramesh Kalkur. Image

courtesy: C.F. John

Participating artists at the installation Cultural Spiral, Ravindra Kalakshetra, Bangalore, April 1993. In the image at the center, artist Ramesh Kalkur. Image

courtesy: C.F. John

The Arbeitesgruppe Gästeatelier Krone (GAK, or Working Group Guest Studio Krone) occasionally hosted artists from various parts of Europe in the Krone studio space, but their main program, for which they raised most of their funds, involved engaging in cultural exchange with countries in the Global South; this included artists from Palestine, Egypt, India, and other parts of Africa such as Jordan, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and the Republic of Congo. India had come to be mapped into the GAK network with Storz’s recommendation of Bangalore in 1997, with an exigent reason being hosting Indian artists practicing contemporary art. In Aarau, the dominant understanding of India was that of a crafts producer, and its visual culture was received primarily through its cheaply available artefacts. By inviting artists from Bangalore, the GAK aimed to shift this narrative and recognize India’s contemporary art practices within the global context.

The idea of “contemporary art” active in the practice of cultural exchange here is perchance in tune with an art discourse alerted to the “global turn” in art production and its reception since 1989. “Global art” had emerged as the corrective principle to world art, championing the critique of Eurocentric museum practices, as it shed focus on biennales and art fairs as the new centers displaying cultures of the other and giving them discursive equality.[29] These centers became hubs for alternative cosmopolitanism and new internationalism, as Third World contemporary art evolved in a new direction, to being recognized as art from the Global South.[30] Parallel to this was the growing discontent with multiculturalism, while artistic production faced the challenge of cultural specificity;[31] the oft-used binary of local/global was the double-edged sword that could take away from the more complicated picture of global migration and its critical possibilities. Thus, the understanding of “site” came to be expanded to not simply signal a location, or a specific locality or region producing a specific culture.[32] Instead, site was thought to be discursively produced; it gestured to a field of knowledge, the site of intellectual exchange or cultural debate. In artistic thinking, much of this converges with Minimalism, the 1960s, and the development of conceptual art, when artists began visibilizing how site is a cultural framework defined by the institutions of art, thereby dislodging its simplification either as a location or as the locus of authentic culture. Thus, what is arrived at here is not just a process-based understanding of art, but also its bleeding into cultural exchange. The practice of artists such as Raghavendra Rao and Surekha were shaped by participating in Bangalore’s spaces of artistic resistance, coming at a time when installation art in the city was often realized through artistic collaboration. It emerged not only as an aesthetic, but also as the preferred form of organizing radically in a post-Fordist economy amid rising jingoistic nationalism and its protectionist attitude toward culture. Thus, in conclusion, such an understanding of contemporary art from India, where the site is repositioned as the location of cultural debate and not as a producer of a readily recognizable national culture, could take forward GAK’s vision to destabilize Aarau’s usual perception of India as a producer of cheap materials.

[1]Since the essay covers the time period of the 1990s and early 2000s, I refer to the city as Bangalore, as it was known until 2014 when it was officially renamed Bengaluru.

[2] Pooja Sood, ‘Mapping Khoj: Idea, Place, Network’, in The Khoj Book of Contemporary Indian Art, 1997-2007, ed. Pooja Sood (Noida, India: Collins, 2010).

[3] Shanay Jhaveri, ‘Is It Still Referred to as “Going Abroad”?’, in Western Artists and India: Creative Inspirations in Art and Design,ed. Shanay Jhaveri (India: Thames & Hudson, 2013), 16.

[4] The Festival of India was a major initiative of the Indian government in the 1980s to promote Indian culture abroad and to forge closer ties to nations which included the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany. For a more nuanced account, see Rebecca M. Brown, Displaying Time: The Many Temporalities of the Festival of India, Global South Asia (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017).

[5] Farhan Karim, ‘Appropriating Global Norms of Austerity’, in Of Greater Dignity than Riches: Austerity & Housing Design in India, Culture, Politics, and the Built Environment (Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), 224.

[6] Jhaveri, ‘Is It Still Referred to as “Going Abroad”?’

[7] Ibid, 12.

[8] Ibid, 13.

[9] See Simone Wille, ‘A Transnational Socialist Solidarity: Chittaprosad’s Prague Connection’, Stedelijk Studies Fall 2019, no. 9, Accessed 2 May 2023 https://stedelijkstudies.com/journal/a-transnational-socialist-solidarity-chittaprosads-prague-connection/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Even as Chittaprosad’s close ally, the Czech Indologist Miloslav Krása, wished for him to find a market in the Indian scene by introducing him to the “successful” M.F. Hussain, who had also exhibited in Czechoslovakia, art historian Simone Wille points out how Chittaprosad resisted such a development, as the artist “also denounce[d] art as a commodity by expressing his disrespect for artists who produce art for money.” Ibid, 8.

[12] For instance, in 2016, the Max Mueller Bhavan in Bangalore spearheaded the bangaloREsidency program as a collaboration between the Goethe Institut and contemporary art/cultural partners in Karnataka and Kerala, primarily Bangalore, inviting young German artists to work in and interact with the city of Bangalore, and its artists.

[13] Shukla Sawant, ‘Instituting Artists’ Collectives: The Bangalore/Bengaluru Experiments with “Solidarity Economies”’, Transcultural Studies No. 1 (2012), https://heiup.uni-heidelberg.de/journals/index.php/transcultural/article/view/9275, Accessed 10 April 2023, unpaginated.

[14] Nick Aikens et al., eds., The Long 1980s: Constellations of Art, Politics and Identities: A Collection of Microhistories (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2018), 10.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Haller and Bortlik were part of an era characterized by a general disillusionment with the infighting between Maoists, Moscow loyalists, and other Marxists., coming to the realization that Marxist ideologies were often too rigid and authoritarian in nature. Wolfgang Bortlik, ‘Idioten in Bermuda-Shorts auf dem Alpenzeiger’, in Kleinstadtrebellion: Von Aarau Aus Die Welt Verändern. (Aarau: Infoportal Aargau (Hg.), 2021), 8.

Haller was inspired by the anarchistic thinking of the likes of philosopher Mikhail Bakunin, especially with reference to ideas of direct action and self-organization. Later in 2016, Haller founded the Zentrum für Anarchie Aarau (ZAA), or the Centre for Anarchy Aarau. His brand of personal politics has been described as “well integrated anarchy.” See Benjamin von Wyl, ‘Gut Integrierte Anarchie’, WOZ: Die Wochenzeitung (website), 16 December 2021, Accessed 7 May 2023, https://www.woz.ch/2150/aarau/gut-integrierte-anarchie.

[17] See Bortlik, ‘Idioten in Bermuda-Shorts auf dem Alpenzeiger’.

[18] See Kleinstadtrebellion, 2021.

[19] Most notably this is known through the May 1980 protests in Zurich—also known as Züri brännt (Zurich is burning)—when the city’s youth revolted against the high subsidies granted to the Zurich Opera House while the government neglected the city’s youth and their idea of culture. See Rob Hamelijnck, ‘Harm Lux, or a Brief History of the Rote Fabrik and the Shedhalle’, in What Life Could Be / the Ambivalence of Success, International Edition Zurich (The Swiss Issue Revisited), Fucking Good Art, #38 (Zurich: Edition Fink, 2018).

[20] ‘Rural, Tribal and Urban Communities-AWS.’ Accessed 23 November 2020, https:// ashadocserver.s3.amazonaws.com/789_SIEDS_Proposal.doc.

[21] Smriti Srinivas, Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and the Civic in India’s High-Tech City, Globalization and Community (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), xxiii.

[22] Iyer, Saroj. “Asian Human Rights: Commission on Women.” The Times of India (1861-Current), Jan 17, 1989. https://search.proquest.com/docview/750698757? accountid=142596. Accessed 23 November 2020.

[23] ‘Rural, Tribal and Urban Communities-AWS.’

[24] See ‘The History of CVA Trust’, Centre for Vernacular Architecture Trust, Accessed 18 May 2023, https://www.vernarch.com/Welcome/About.

[25] One of these was Shramik, “a co-operative of craft persons initiated by late R. L. Kumar in the late 1980s,” which then grew into The Center for Vernacular Architecture Trust. Ibid. Another initiative was Janamadhyam, “a screening network and production infrastructure for grassroot action” by Chalam Bennurakar, a college dropout and former signboard painter turned documentary filmmaker. Chalam was also active in conceiving screening networks to visibilize the medium of documentary filmmaking, building platforms to showcase works from around the world. Further, also a member of Vimochana, he pushed for the screening of films based on women’s issues at the Bangalore Film Society. See ‘Remembering Chalam’, Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, accessed 18 May 2023, https://ficart.org/remembering-chalam.

[26] It was founded by activist Georgekutty A.L., as it saw additions over the years in the form of artists Suresh Jayaram and Babu Eshwar Prasad, activist Altaf Ahamed, and filmmaker Kavitha Lankesh, among others.

[27] In India, an important development was the rise of the Autonomous Women’s Movement in the 1980s, where non-funded collectives eventually turned into externally funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in the 1990s, leading this shift to be perceived as a loss of collective feminist politics that was based on autonomy.

[28] C.F. John, “Cultural Spiral”, Unpublished manuscript, email correspondence with author, 5 November 2019.

[29] See Belting, Hans, Andrea Buddensieg, Peter Weibel, and Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe, eds. The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds. Karlsruhe, Germany: Cambridge, MA; London, England: ZKM/Center for Art and Media; The MIT Press, 2013.

[30] Miguel Rojas-Sotelo. “The Other Network: The Havana Biennale and the Global South.” The Global South5, no. 1 (2011): 153–74.

[31] See Simone Wille, “Specificity of Location,” in Personal/Universal, exhibition catalogue, Vienna: Hinterland Galerie, 2016.

[32] See Miwon Kwon. One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 2002.

Shramona Maiti completed her MPhil in Visual Studies in 2022, with a thesis titled “The Shaping of Participatory Art in Bangalore: Dialogue, Dissensus, and the City.” She was a researcher in residence at the Gästeatelier Krone (Aarau) during the months of November and December, 2022, focussing on their history of cultural exchange.

The author would like to thank Wenzel A. Haller, Wolfgang Bortlik, Chinar Shah, Valentin Hauri, Michael Omlin, Eva Mühlethaler, Hildegard Spielhofer, Sabine Trüb, Patrizia Jegher, Katrin Zuzakova, Sureshkumar Gopalreddy, Surekha, and C.F. John for their generous help at various stages of research for the essay.

Link to Part 2 of the essay: