Sides and Accompaniments: The Pagal Canvas Backyard

Stuti Bhavsar

Published on 13.12.23

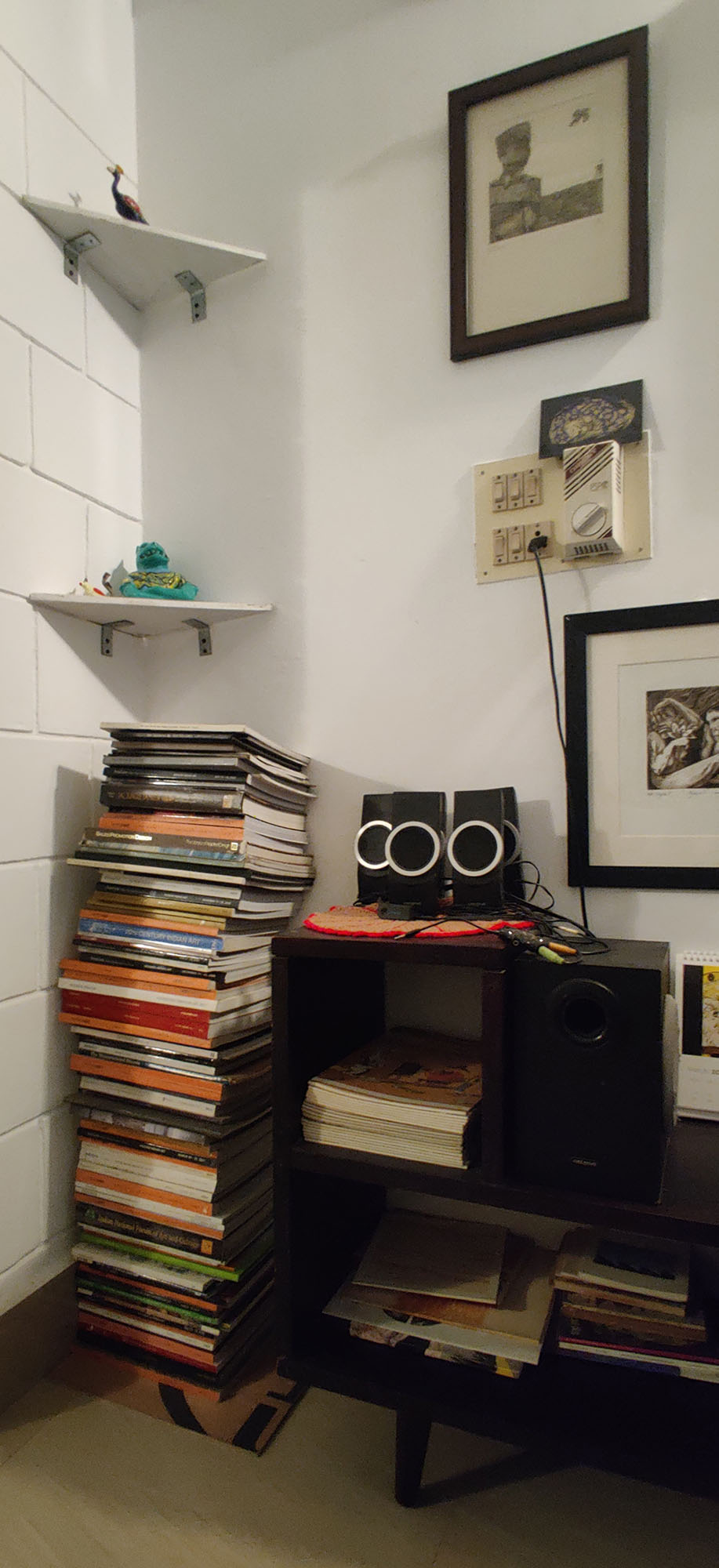

The Pagal Canvas Backyard. Image courtesy: the writer.

On my visit to the Pagal Canvas Backyard in Sanjayanagara, Bangalore, I noticed how well their library and print collection reflected their various practices. The comic Jai Kali Android Wali by Pagal Canvas, the self-publication collective on which the Backyard’s name is based, is nestled amidst a host of other works. On its left is Paresh Maity’s book Infinite Light—recently launched by Gallery Sumukha where Mohit Mahato, the founder of the Backyard works—looming large on the display shelf, directing the eye toward the wall. Here, between prints gifted to the space by interns and workshop participants, is a cyanotype print by Sonali Chorawala, one of their first resident-interns, and Kush Kukreja’s plate litho print that the Backyard helped produce. These form the backdrop to Justice Makers, a zine put together by Agami, where Pagal Canvas consulted with printing. As I gazed at the shelf in its entirety with my eye traveling back and forth, as within a comic book, I couldn’t help but notice the art magazines and catalogues that formed a towering column beside the shelf and, like tentatively laid platforms, also filled the shelves below, providing a base for more works to come.

I thus saw the shelf become a structure, akin to a three-dimensional comic book. The prints, books, and their arrangements acted as panels containing content produced by commercial and independent publishers, and showcased practices enabled by galleries and alternative art spaces. The tentative space that lay between them served as gutters—a divisional device used between panels in a comic—provoking one to read between moments, spaces, and gestures, and understand their relationality.

To piece together some of these relations and organizational possibilities generated by sequential and visual narratives, this essay looks at Pagal Canvas Backyard’s print- and service-based practice, within the environment of artist-led initiatives that have come to characterize the art scene in Bangalore.

[L] Anand Shenoy (L) and Prakruti Maitri (R) assembling a publication at CKP’s Printmaking Studio, 2018.

[R] Pagal Canvas’s stall at the Chitra Santhe, CKP, 2018 with Be Kind, Rewind—a scroll consisting of works by second-year students in response to a mapping-based class exercise.

Pagal Canvas, from which the Backyard emerged later, is a self-publishing practice initiated in 2017 by Anand Shenoy and Mohit Mahato, then both final-year students at College of Fine Arts, Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath (CKP), Bangalore. Mohit was interested in Anand’s comics, multiples, and zines, and the scope of production and exhibitionary flexibility they afforded. What started as a collaboration between them soon grew into a practice that addressed a need stemming from a lack—as with many alternative art spaces in the city—caused by an excess of art production and circulation that remains largely commodified and exclusive.

Initially, as students themselves, Anand and Mohit catered to other students as their prime audience. They worked toward addressing a lack of communication within the student community with regard to their practices, class exercises, and discourses, and their limited engagement across disciplines. As recounted by Mohit, most of the production happened post studio hours at CKP, where those interested gathered to print, assemble, sew, or fold the spreads, forming an organic community of like-minded students interested in pursuing possibilities heralded by the process of book-making and other varied print-based methods.

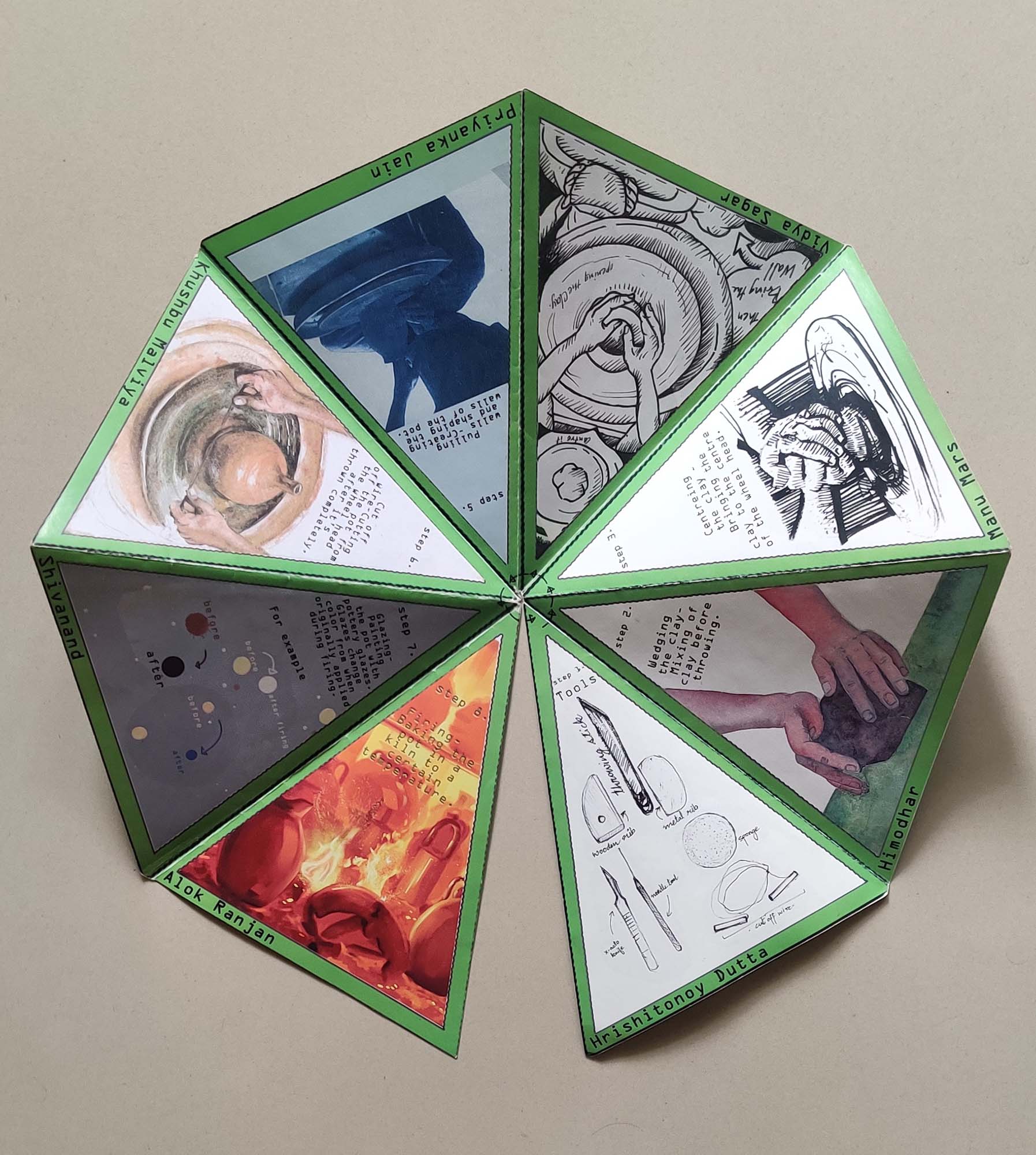

For instance, Pagal Canvas’s second publication, Atom Timma (2017), helped Sidhartha SN (then a student of printmaking) structure, condense, and re-interpret his two years of practice—executed in various printmaking techniques—in the form of a graphic narrative. The form of the graphic art book facilitated a better outreach of his works and held audience interest for a longer duration than a standalone print or a lengthy portfolio would have. Driven by peer-learning, their third publication, It’s Shivu Time (2018), became a collaboration between Shivu Mahesh (then a student of sculpture) and eight others from departments as diverse as Art History and Painting. Each step was interpreted by the student in their chosen medium of expression, leading to the creation of an eight-step guide that taught the basics of pottery.

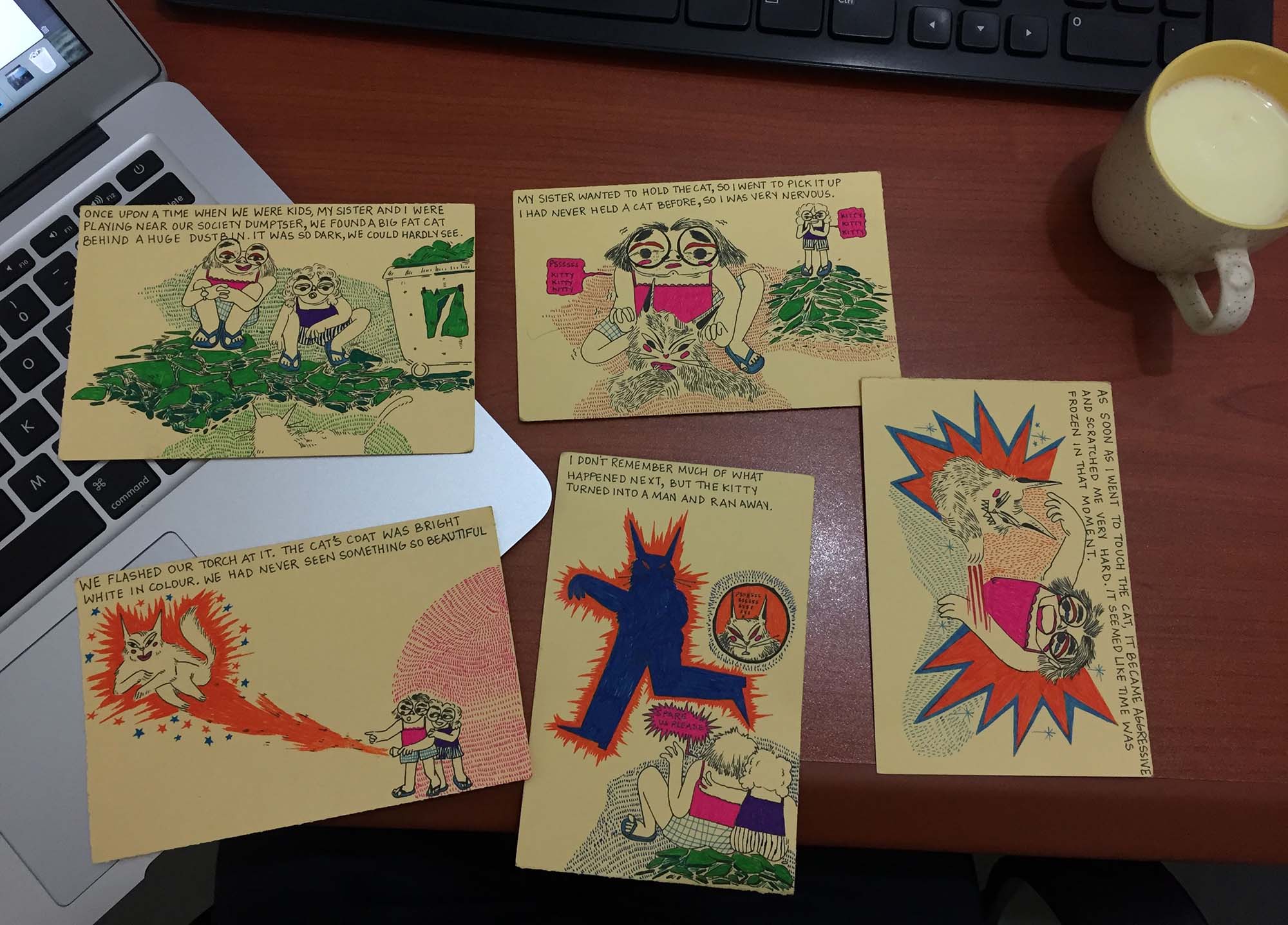

Pagal Canvas generated a pocket within mainstream publishing, tuning existing processes of production and methods of circulation to their low-budget needs and experimental formats. For example, in the Postcard series(2018), 20 artists were invited through an open call to work with five postcards each and generate their own narrative in five frames; each postcard was envisioned as a frame. The individual frames (related either by theme or narrative to four others) were later sent out through the postal system to different contributors, breaking the narrative, and at times creating a new one based on chance.

As students of CKP, with the institutional infrastructure in place, they did not have to hunt for space, nor directly set up the facilities needed. Most of their publications then were priced below 50 rupees, sometimes as low as 10 rupees, making it easily affordable for the student community, who remain their primary audience and collaborators to date. Later, as fresh graduates, they felt the need for a studio-like space where practices could be supported in terms of development and exchange of ideas, experimentation in different media, and production. This stemmed from sensing a larger issue of recent graduates and novices struggling to produce and exhibit their work, navigate the art field, and financially sustain themselves as well as their practices. Pagal Canvas was thus envisioned as a meeting ground for budding and aspiring artists, novices, and graduates, where matters pertaining to art could be negotiated collectively and practices could be expanded, explored, and shared with ease.

After graduating in 2018, Anand and Mohit worked from their respective homes, where Pagal Canvas existed as a distributed, psychological convening space, made apparent during discussions and collaborations, and their seasonal participatory desk at the Indie Comix Fest, which alongside their active social media page, became their corporeal address.

[L] Ayesha Punjabi’s narrative from the Postcard series, 2018.

[R] It’s Shivu Time, 2018.

With Anand and Mohit as constants, the space gradually brought into its fold potters, photographers, writers, translators, designers, and quilt enthusiasts, among others. With an ever-mutating network, they engaged with works in multiple languages and formats ranging from single-spread comics, interactive photobooks, and anthologies based on open calls to travelogues based on class assignments, and DIY comics where personal narratives could be created out of loose printed spreads. Moreover, besides workshops, their programming also included organizing writer’s jams where exercises were devised to understand the relationship between image and text, ways of reading an image, and the evocation of visuals using just text.

With their practice, what becomes apparent is how the creation of heterogenous visual narratives generates a space—often unforeseeable, with the Postcard series for instance—where the objective of creating encounters supersedes the intention of creating an object-oriented artwork. In their case, the latter becomes a mediator, generating avenues for collectivization and platforms for collaboration and circulation, where ways of handling, seeing, experiencing, and negotiating with artworks are continuously reworked.

The practices Pagal Canvas fostered also allowed for ways of being in space—how one contains it and is contained in turn. Even if the gatherings with CKP students and Anand and Mohit’s peers were short-lived in actuality, they were persistent in memory, seeing how many came later on board, either with the Backyard or Pagal Canvas as collaborators. Moreover, Mohit recounted how contributors like Akkash B. and resident-interns like Sonali Chorawala have represented them at fests and pop-ups of their own initiative when they couldn’t attend them, helping get an audience for Pagal Canvas’s works across Mumbai, Kochi, and even Agartala. This kind of self-driven initiative fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility toward furthering the space, reducing the burden on the founding few, who remain the enterprise’s key faces and names. Then, as much as it facilitates space-making, it also promotes different forms of space-claiming by contributors—even if only temporarily so—in terms of speakability, agency, responsibility, and having a stake in the maintenance and diversification of the produced space. Today, Mohit manages operations, administration, and correspondence from Bangalore, and Anand works from New Delhi, where he is also developing a personal range of comics, produced independently from Pagal Canvas.

The Pagal Canvas Backyard was opened by Mohit in 2020 as a distinct entity, rooted in Pagal Canvas’s attempt at generating a platform that enabled a space for conversations, while creating a facility that could provide printing-based services,[1] internships, residencies, open studios, and undertake commissions and workshops, among others. Mohit envisioned a studio that could cater to his own needs, since he was considerably involved in the technicalities and production processes of the books at Pagal Canvas. However, with a growing interest in printmaking, he sensed the need for a space for those interested in not just exploring print-based processes, but also ways in which these could add a new contour to their present practices. For instance, Radha Patkar, a recent resident-intern and a student of illustration at NID Bhopal produced a flip book by creating each frame using the technique of cyanotype, narrating her experience of using an oven and baking at large. The process of learning cyanotype in turn became an exercise in understanding time as an important aspect of image and form generation.

Furthermore, in recent times, most of Pagal Canvas’s books have been screen-printed at the Backyard, often sewn, hand-cut, and individually folded to suit the design. Printed in limited editions of 250, the returns from the sales help in part with the space’s operation. The space is maintained, and print- and narrative-based endeavors are further fed by other programming initiatives such as hosting workshops around various printmaking techniques, to even planning and pitching one’s projects effectively, like the workshop on grant writing facilitated by Anusha Vikram in 2021. True to their student-oriented approach, in 2022 they temporarily hosted a personal collection of comics such as ‘Commando’ (published by DC Thomson) of Mark Mathew, one of their collaborators and then a student of printmaking at CKP, to understand the genre of war comics and their functions. Each program in turn becomes an opportunity to open their own and students’ collections/works to dedicated but also new audiences, and simultaneously attend to the current needs of the student community, budding artists, and novices, in keeping with contemporary discourses.

[L] A former collaborator Prakruti Matri’s Open Studio at the Backyard, 2022.

[R] A workshop on cyanotype conducted parallel to the International Print Exchange Programme, 2022.

Parallelly, the Backyard began collaborating with various printmaking exchange programs, where they sometimes helped produce a participant’s print, and other times offered mentorship and technical guidance to the organizing institute in curating and designing print folios. In one such exchange—the International Print Exchange Programme, 2022—the rule was for each portfolio to travel to a different location, where each contributor was based, and for the folio to be exhibited there. Since Mohit was participating and had access to Gallery Sumukha (where he has been working since 2018), he chose to display the prints there as part of his curatorial endeavor. The show provided a glimpse into aspects such as how printmakers globally are approaching printmaking as a medium, material innovations within print-based techniques, and the print’s changing social function. This was a departure from Gallery Sumukha’s usual practices, given that their curatorial interests usually lie in presenting established artists and works from their collection, where the focus on printmaking is typically limited, even when it is a part of exhibitions.

Then with the Backyard, what also becomes interesting is the many roles that Mohit plays and how they feed into each other—an artist represented by Sumukha, where he also assists with curation and gallery administration, while being the founder and a facilitator at the Backyard, helping realize students’ and artists’ projects. While a lot of artist-initiated spaces are looked at as being alternative, they aren’t always completely independent of the ‘institution’, that often provides stability in terms of finances or resources.[2] It is therefore crucial to look at how institutional power and resources are being distributed, or even mimicked, and how social relations between art spaces are being formed and reworked.[3]

Sumukha’s director, Premilla Baid, helped finance the Backyard initially and, in Mohit’s words, remains an important mentor as he learns to run a gallery space, understand funding models, and recognize what presenting artworks and mediating their reception entails. This helps him work through curatorial possibilities at the Backyard, whether it is deciding the order within an anthology, possible programming around the books and their relevance, or even opening the Backyard into an exhibitionary and discursive space for works that never received physical reception due to the Covid-19 pandemic (when universities were shut and most students lost out on a proper display opportunity). The Backyard’s library also contains several books, catalogues, and art magazines from Sumukha’s collection. Instead of them lying unused in the storage, the library makes available these otherwise expensive magazine subscriptions, and catalogues that aren’t necessarily for sale and difficult to access post an exhibition, facilitating a know-how of different artistic practices.

Work by Mohanavathi, Behind the Seen, at 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery, 2010. Image courtesy: Surekha.

Work by Prabhakar

DR, Behind the Seen, at 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery, 2010. Image

courtesy: Surekha.

Work by Prabhakar

DR, Behind the Seen, at 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery, 2010. Image

courtesy: Surekha.Many artists occupy in-between positions such as Mohit’s, where their time is split between the office hours that fill one’s day (classified as a job) and the sliver of hours surrounding the former (usually identified as practice).[4] These jobs create a sense of security that sustains livelihoods and is integral to the liberating act of artmaking for many. They become places in Yi-Fu Tuan’s formulation where, “Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other.”[5]

This quote prompts one to rethink the not-so-easy differentiation between space and place, the many roles artists play, the understanding of what practice is, and where creativity gets located. As I mulled upon this, the exhibition ‘Behind the Seen’, curated by the artist Surekha in 2010 at 1Shanthiroad—another artist-initiated space in Bangalore—provided a way of seeing the space between artistic and non-artistic roles as being rife with possibilities, instead of them being distinct. The exhibition acknowledged people who have facilitated practices in some key art institutions in Bangalore as employees, and who don’t primarily identify themselves as artists. In the exhibition note, Surekha writes about how each of the employees’ ties with the artist community and their engagement with diverse practices helped present their own artistic forms, material sensibilities, and concerns—without a formal training as such—that the works in the exhibition bring to focus.[6]

Mohanavathi, a former caretaker at 1Shanthiroad for over two decades, made dolls using scraps of fabric that marked patchy memories of people—residents at 1Shanthiroad (who occupy the space momentarily) and her friends on the street (who are usually displaced and on the move)—and negotiate with meanings of space-making, formation of the self, and belonging. Opposite Mohanavathi’s works lay Prabhakar DR’s works, comprising of pedestal-like sculptures that he fashioned out of used and found machinery parts. They evoked the monumental presence of the appliances that facilitate tech-based work and aid film screenings at Goethe-Institut, Bangalore, where he worked as a technician for four decades.

Currently an artist represented by Sumukha, at that point a manager at 1Shanthiroad, and formerly a cop, Shivaraju BS’s exposure to photographic practices led him to create a photo series based on the lives of workers and farmers—a community to which he belongs—involved in various kinds of manual work. He intended to rework the gaze toward these subjects and attempted to “frame them rightfully.”[7] Subbaiah, who worked as an assistant at a short-lived artist-run space in Bangalore called Samuha, also employed photography to share his observations from the viewpoint of a mason and a vegetable vendor, among other occupations. The photographs encapsulated his everyday negotiations with materiality (rabbit’s fur, and real and artificial flowers, for instance) and their changing connotations, and helped rethink their traditional, modern, and sustainable uses.

Addressed as artists in the show, and otherwise as employees, assistants, or cultural workers within the given institutes (both mainstream and alternative), I wonder if exhibiting one’s work in a gallery or a cultural space becomes the only marker of being identified as an artist and a creative.

These managerial, technical, and assistive roles are also taken on by artists in varying degrees, that at times include creative work and labor—be it an artist producing editions for another artist, providing inputs and feedback on visuals for print, preparing and processing a plate for printing, providing documentation and archive-based services that are integral to the reception and circulation of many artists’ practices, or producing a commissioned work, among other kinds of work.

All these services and inputs are often related to and stem from one’s artistic practice, be it the self-guided or institutional art training that one has undergone to develop material handling and sensibilities, or a long-term engagement with specific techniques and medias that have been honed by way of their use in the provider’s personal practice. Sometimes it is the other way around, as evident in Shivaraju BS’s case, where his artistic practice got shaped by a continued engagement with new skills developed, things realized, and interests cultivated in the due course of service.

Practice then—that many times draws upon both creative and economic pursuits—gets located in the wide and interconnected spectrum where the artist and the cultural worker aren’t necessarily opposing roles one switches between as per the need.

[L] Pagal Canvas publications at Zine Festival, organized by Kānike Studio—an artist-run space that offers facilities for various photographic practices, 2022.

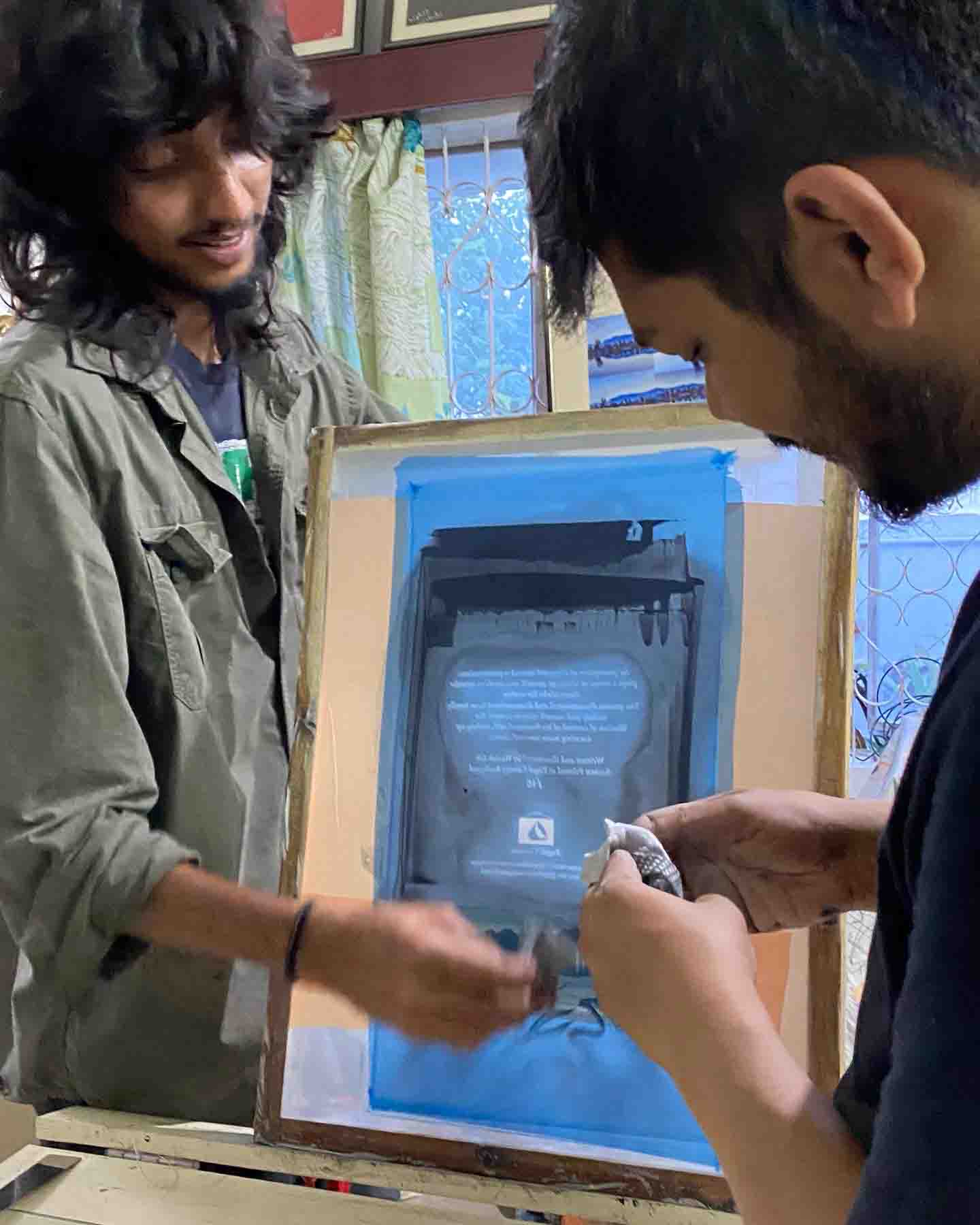

[R] Siddharth SN (L) and Mohit Mahato (R) screen-printing a Pagal Canvas publication, 2022.

Expanding on these relationalities, and the alliances they result in, the Backyard’s operations also exemplify how many artist-initiated art spaces in Bangalore are supporting one another by providing different kinds of services—another defining feature of art practices in the city today. If a grant from The Experimenter helped realize the production of Jai Kali Android Wali, Pagal Canvas’s most ambitious project till date, its reception through an exhibition of the spreads and the book launch would have been unlikely without the space lent by 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery, its openness toward hosting varied practices, and its wide audience network.

In a similar vein, Mohit recollected how Jayasimha Chandrashekar from Atelier Prati not only helped gauge considerations that are important in building a printmaking studio, but also manufactured a press for the Backyard, suitable for etching and plate-based lithographic printing. The Atelier’s studio head Sidhartha SN, who facilitates print-based production for artists there, is also one of Pagal Canvas’s earliest collective members. Helping Mohit get the print-based facilities in operation, he continues to be a constant support to the space, troubleshooting whenever necessary and helping with large print productions on various occasions.

A screenshot of space donors’ mention within the colophon page in Vrishchik, Issue 11-12, 1970. Image courtesy: Gulammohammed Sheikh and Asia Art Archive.

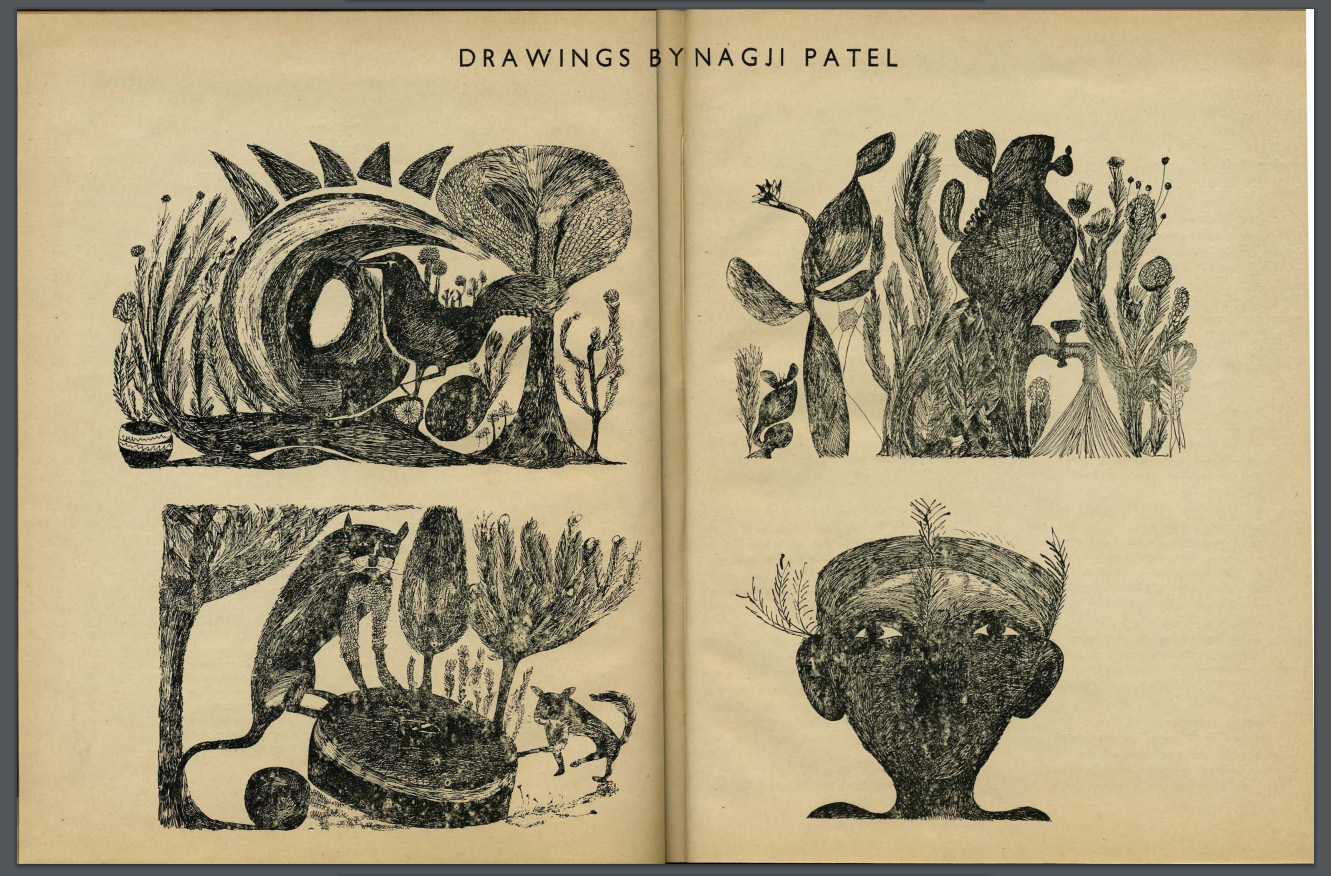

A screenshot of space donors’ mention within the colophon page in Vrishchik, Issue 11-12, 1970. Image courtesy: Gulammohammed Sheikh and Asia Art Archive. A screenshot of Nagji Patel’s drawings in Vrishchik, Issue 3, 1970. Image courtesy: Gulammohammed Sheikh and Asia Art Archive.

A screenshot of Nagji Patel’s drawings in Vrishchik, Issue 3, 1970. Image courtesy: Gulammohammed Sheikh and Asia Art Archive.The services offered by such spaces create a solidarity economy, depicting irregular, but mutual modes of financial sustenance, be it through space-renting, manufacturing machines, production, or commissions, where the artistic and the commercial coalesce. Returning to the publications, this amalgamation brings to attention aspects of advertisements, which within the published space have artistic and proprietary undertones.[8]

In trying to understand how artists as publishers approached advertisements, I was reminded of the mention of ‘space donors’ within Vrishchik, a publication edited by artists Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar, and run out of Baroda between 1969 and 1973. Like Pagal Canvas, their low-cost publication became a vehicle for self-organization—made possible by writers and artists wanting to see the possibilities of practice beyond their individual endeavors—and in Vrishchik’s case, specifically also for artists’ dissent against state-based art institutions like Lalit Kala Akademi. With each issue often “supplemented by a free original modest artwork—a linocut, woodcut, lithograph—to be slipped out and tacked/framed by the subscriber,”[9] the publication acted as a space of dialogue for artists and creative practitioners on matters pertaining to art but also social concerns of the time, containing translations and writing in varied formats by artists, critics, and poets, among others.

The publication was primarily funded by the editors and initially run without any fixed rates for subscription, where collaborating artists and well-wishers contributed in their own ways. However, even if marginal—but as mentioned in the first issue and making an appearance from the fourth issue onward—the publication was also financially supported by space donors. Whereas the idea was to accept advertisements from them, against their contribution, as space donations (in turn creating a space for main content to

come),[10] given the editors’ aversion toward featuring the advertisements, none appeared in the issues. Duly acknowledged in the colophon, the donors comprised of friends, commercial industries, and private businesses, where individuals sometimes made a donation in remembrance of a loved one. And as indicated in Vrishchik (Year 1, Issue 3), at times the donor’s support was specific to a part of the production process, observing for instance how “The blocks for two drawings of Nagji Patel [were] donated by western India Motor Car Co, Bharat Udyog Hat and Dazzle paints and chemicals, Baroda.”

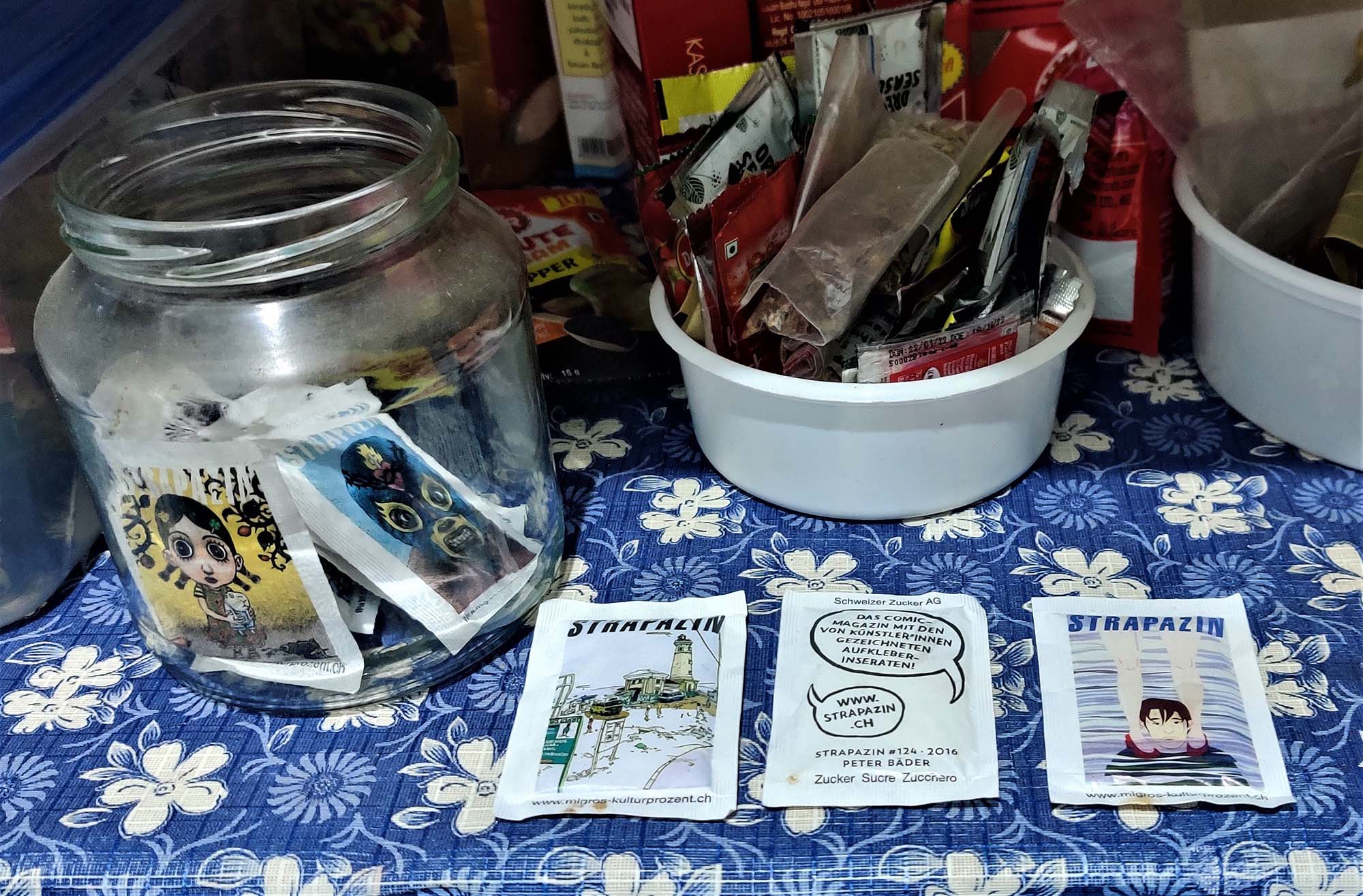

Sugar sachets by

Strapazin at the Backyard’s kitchen, 2023. Image courtesy: the writer.

Sugar sachets by

Strapazin at the Backyard’s kitchen, 2023. Image courtesy: the writer.If Vrishchik served as one model to gauge how the commercial was also dealt with as necessary in the near-absence of gallery or art-institutional funding, we see another in Strapazin’s approach to advertising, as shared by Mohit during my visit to the Backyard, where the promotional space became an exhibitionary vehicle for artworks. Strapazin is a publishing practice initiated by artists in Switzerland who were employed by the newspaper agency ‘Blatt,’ which, like Pagal Canvas, publishes and promotes artists who are not necessarily established, using content and form that isn’t aimed at being homogenous. For them, advertisements are the main source of funding alongside subscriptions, where companies can get their event posters designed and illustrated by Strapazin’s team, which are in turn distributed with their issues. Other times, they collaborate with cultural institutes, printing the covers produced by the issue’s contributors and those made for funders, on sugar sachets for instance—dissolving the artworks’ preciousness and reaching audiences never initially conceived of—sold and used during comic fests like Fumetto. Their practice is reminiscent of how the Backyard also prints illustrations from their own works and comics on tote bags and stickers, when undertaking a commission to create customized totes for bookstores like Goobe’s Book Republic, among others.

- All images are courtesy of Pagal Canvas Backyard and Mohit Mahato, unless otherwise mentioned.

[1]Equipped with facilities for woodcut, linocut, etching, lithograph, screen-printing, and cyanotype, amongst others, its users range from school students and laypeople wanting to learn hobby-based techniques, to even starts-ups and small-scale businesses interested in getting their souvenirs customized.

[2]Pushpamala N, in her survey of alternate art spaces in Bangalore, addresses the need for institutions and galleries, and the dangers of seeing them as solely antagonistic. She explains, “Perhaps the notion of a professional gallery has never set in firmly, and many active artists do not have a representing gallery, preferring to show in rented public spaces, consulates or mainly in group shows. I think all of us have done the gamut. At the same time, there is a need for good art schools, museums and professional galleries, biennales and art fairs to anchor the art scene in a way, draw large audiences, and to historicise art as well as make it commercially viable.” For more, see: N, Pushpamala. “OTHER PLACES, OTHER FACES”, Issue 02: Gallery, TAKE on art, 2010.

[3]The relationality makes me wonder about the traits of the institution that the alternative space absorbs and reflects. Often, artists and collaborators aren’t compensated monetarily, and the value is to be understood in cultural and symbolic terms, vis-à-vis the exposure and support that the platform facilitates. Secondly, residency and exhibitionary spaces that portray themselves as being synonymous with home and familial values also raise questions about how labor and fair-pay practices get addressed and negotiated with. Many a time, artistic and manual labor goes unacknowledged and unpaid in the name of creativity, familial care, and collaboration, where exploitation continues in the garb of maintenance of the space and the expected sense of service that one would have toward kin, creating a forced sense of fraternity that is good for optics’ sake. Although this topic is beyond the scope of the essay, it does make me reflect on whether all alternative spaces are non-exploitative and on the different ways in which the latter plays out, and the juncture where, over time, they become the mainstream institutions that they set out to counter in the first place.

[4]Respectfully appearing only on CVs and bios, and otherwise whispered as a side-line by recent graduates and young artists, jobs are often looked down upon as a non-practice, inducing guilt about one’s not-so-full-time commitment to art and raising a question about the genesis and sustenance of ‘practice’. For more on this ambivalent relationship, see: Diehl, Travis. “Why Is a Day Job Seen as the Mark of an Artist’s Failure?”, Critic’s Notebook, The New York Times, 2023.

[5]Tuan, Yi-Fu. “Space and Place - The Perspective of Experience”, University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

[6]WHAT'S COOKING@1.Shanthiroad Studio: August 2010 (1shanthiroad.blogspot.com) and documents related to the exhibition, shared via an email correspondence by Surekha.

[7]Exhibition note of ‘Behind the Seen’, 2010, as shared by Surekha.

[8]See: https://www.themediaant.com/magazine/take-on-art-magazine-advertising and https://www.themediaant.com/magazine/art-india-magazine-advertising. Similar to how sea-facing apartments are more expensive, advertisements on jackets and covers constitute ‘premium’ services within mainstream art-related magazines.

[9]Kapur, Geeta. “Signatures of Dissent”, Art India Magazine, Vol.VI, Issue II, 2001.

[10]As recounted by Gulammohammed Sheikh in a textual correspondence, Vrishchik was independent with regard to content and design, with the frequency of publishing being determined by the editors’ own schedule. However, funding seems to have a bearing on the publication, where in their first issue it is mentioned how the number of pages in a specific issue was directly contingent on the funding received. Often times, the editors announced upcoming issues, with details of content and contributing writers, to fundraise and materialize their plans.

[11] While Hirata speaks of an artist’s supporting role, I feel that his observations are also applicable to an artist-initiated space’s practice that facilitates production. For more, see: Lubitz, Joey. “Art As Negotiation: Jason Hirata Interviewed by Joseph Lubitz”, BOMB Magazine, 2020.

Stuti Bhavsar is a visual practitioner, writer, and researcher based in Bangalore. You can reach her at stutibhavsar11@gmail.com