Interview with Suman Gopinath and

Edgar Demello

(CoLAB Art + Architecture)

Nihaal Faizal

Published on 30.09.2023

Nihaal Faizal [NF]: So, thank you Suman and Edgar for taking the time out for this. I’ve been very interested in the story of CoLAB. It’s something that I never got to visit or engage with firsthand, having moved to the city only years after, but it’s something that comes up a lot in conversations, in fond recollections, when I talk to friends in Bangalore. So I’m grateful for this chance to hear more about it. To start, could you tell me how you came upon the name CoLAB?

Edgar Demello [ED]: I think the name is sort of self-suggestive. In principle, a collaboration, but also a laboratory. We were interested in disciplines that are connected, like art and various strands of it, and architecture and the various strands of that. And so we wanted something that indicated that cross disciplinary nature. So, CoLAB seems to have been the name even before we quite knew where we were heading.

Suman Gopinath [SG]: And even the way that it was written—it was ‘Co’, ‘LAB’. ‘Art and Architecture’.

ED: Yes—Art plus Architecture. We always write it differently, Suman and I. I write ‘Art + Architecture’.

NF: Right. And you were telling me the story of how it began, how before CoLAB, there was a bookstore?

ED: Actually, it was first an architecture gallery. The bookstore was sort of incidental because of my passion for books and reading. I was warned by a very dear friend who said, “Be careful. Architecture gallery: tick mark. Bookshop: which architect reads?”

(Suman laughs)

It was a prophetic sort of thing that he had said. But I was getting books from very good sources—the Architecture Association in London, and then from Rotterdam and Amsterdam, the Architectura + Natura. So there were very good books that came in, and later I gave quite a part of it to CEPT. So, the bookshop was sort of incidental, and then it died a natural death, though it became a little reference library for a while. But, the gallery was, in principle, a common platform, which didn’t exist at that time—of practice, academia, and teaching. Most of the patronage came from students. I don’t think there were too many, so-called, established architects that came, unless I had a show on them. Before that there was something called BASE in the same space. We never knew what the acronym was, until Claire Arni’s father said, “The way you guys conduct yourselves, I guess it could be Beer And Slides Evening.” We were not particularly incensed by it, but we had found a smart one for ourselves—Bangalore Architects Society for Education. So BASE became tAG&B [the Architecture Gallery & Bookshop], and tAG&B slowly morphed, together with Suman, into CoLAB in 2005.

NF: So, tAG&B was something you were running. And you designed the space as well?

ED:Yes, specifically for the gallery.

NF:And you owned the place?

ED:Yes, it is in Shah Sultan Complex on Cunningham Road. A very small place, about 850 square feet. But it can occupy about 60–80 people.

NF: How did the two of you come together?

SG:Through Sakshi Gallery. Edgar was a patron and collector.

ED: That is not true, but aspiring still!

SG: Edgar used to come often to Sakshi Gallery for the exhibitions, while I was working there. I worked there for about eight years (1991–98). In 1999, I got a bursary to study Curating and Arts Administration at Goldsmiths College, University of London. On my return, I left the gallery as I didn’t want to work in a commercial set-up any longer and wanted to do something on my own. It was then that Edgar very generously offered the tAG&B space to me, saying, “Let’s do something together here—art and architecture.” We both imagined CoLAB to be a kind of non-institutional and non-commercial space, where people could experiment. Like Edgar said, a laboratory, where artists and architects could test ideas. It was a platform for exchange, and that’s really how CoLAB came to be.

NF: Did you have specific models and references in mind when starting CoLAB?

SG: Rather than a model, there was a small experimental space in Berlin called Sparwassar HQ run by the artist Lise Nellemann that really made a huge impression on me. This was a platform for the exchange of ideas through exhibitions, talks by artists and theorists, video screenings, live performances, you name it. That was when I realized that it was possible to do amazing things with limited money but unlimited ideas.

ED: And starting CoLAB was quite a quick process. It didn’t gestate for too long.

SG:That’s because Edgar already had the space. We had one employee to whom we paid a modest salary and Edgar looked after the rest. This is also why we couldn’t sustain it for too long. But short-lived though it was, it had quite an impact on the field. We had interesting exhibitions, talks, and it was a very accessible kind of space. Unlike a commercial gallery, which often feels unapproachable and sacrosanct, CoLAB was able to bring in both the ‘intentional audience’—people who intended to come for something anyway, and the ‘incidental audience’—those who just dropped in. So it was a really nice mix.

NF: Could you tell me a bit more about what else was happening in the city at that time?

ED: There used to be one very small gallery called Kritika Art Gallery. On Saturdays we had a sort of ritual. We would go to Koshy’s, spend a couple of hours there, then go to Kritika, and then to Premier Bookshop. And if you had some more time, you landed back at Koshy’s. And this was like a circle in that part of town. I think Sumukha Gallery came much later.

SG: Yes, later. I remember the owner of Kritika Art Gallery, Kausalya Dayaram, coming to Sakshi very often, but that was a long time ago. Kritika, Sistas (earlier called Kala Yatra), and Sakshi Gallery had all closed by the time CoLAB opened, I think. Sistas and Sakshi were two of the first professionally run galleries in the city. Around the time of CoLAB there was Sumukha Gallery, Galleryske, and quite a few artist-run spaces—Suresh Jayaram’s 1Shanthiroad Studio/Gallery which is going to turn twenty this year, BAR1 [Bangalore Artists Residency One] which was an artists’ collective, and a number of other projects initiated by artists that took place either in their own studios or other unconventional spaces in the city.

ED: Was there nothing in South Bangalore?

SG: No, nothing in South Bangalore.

NF: And was the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan active?

SG: Very active. I remember when I was in Sakshi in the late 1990s, Heiko Sievers, who was director of the Goethe-Institut in Bangalore then, collaborated with the gallery on many projects. And after Sievers, Evelyn Hust, who succeeded him, supported CoLAB and several other art initiatives in the city. The Institut collaborated with CoLAB on a year-long lecture series called Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture.

NF: So once you decided to start CoLAB, did you formalize it in some way, were you a non-profit trust or a company?

ED: Yes, it was registered as a trust.

NF:And how was the funding coming in? Were you able to secure funding as a trust through donations and grants?

ED: We didn’t go... I mean, I don’t know. Sometimes we found a person in the industry to support it. It could have been a company like Schneider and they would underwrite something. One and a half lakhs—not a big amount. But apart from that we were putting in our own money.

SG: We were putting in our own money and for the rest, we looked for collaborators. For instance, the year-long lecture series was funded entirely by the Goethe-Institut; the catalogue for the exhibition ‘Around Architecture’ was funded by the Bodhana Trust in Mumbai, and so on.

NF: And, there was only one salaried employee?

SG: One salaried employee, yes.

NF: And neither of you were receiving a fee for this?

SG: No.

NF: How were you sustaining?

ED: Love and fresh air!

(everyone laughs)

SG: I had just come back from Goldsmiths, and I was full of enthusiasm. There was Edgar’s space and, we had a few people to collaborate with…

ED: Let me put it this way, most of the initiatives were Suman’s. I was running an architecture practice and that practice was beginning to get a little healthy. So I have to say that my inputs at CoLAB were limited in terms of programming and organizing.

SG:Our initial idea was to see where art and architecture would intersect. But what was also nice was that we had lots of architects, young people, coming in for all the art exhibitions and vice versa.

ED: Yes, but if I am honest, most of the events were ultimately art-related. There were very few that were architecture-related. I think the innings of tAG&B was over. There was a little carryover, of course, and it ended wonderfully with one of our masters, BV Doshi, giving a momentous talk.

SG: That was fantastic. It was in January 2011 at the NGMA and we had about 300 people inside. And another 200 outside listening through the audio speakers. I mean he was like a rockstar…

ED: That’s what I wrote when he died a few months ago. Somebody said it was like an architecture concert!

NF: So the physical space itself was fairly short-lived, right? You didn’t have it throughout CoLAB’s existence.

SG: No, CoLAB as a physical gallery space lasted for about three years from 2005–2007.

ED: So it began as an office, lasting perhaps six or seven years. Then for five years it was a gallery—tAG&B—and then about three years it was CoLAB. Then of course CoLAB went siteless.

NF: What led to that?

SG: As Edgar was saying, basically I was programming the space, while also curating projects outside the country, but when I was traveling there was nobody to look after the gallery. As neither of us wanted to give up CoLAB, we thought of other ways of keeping it going, and that’s how CoLAB evolved from a physical space to a research-based curatorial program.

ED: And I had started to get busy not only with my architecture practice, but also teaching in Mysore, and that took almost two days of my time every week. So running the space became a little difficult.

NF: What has happened to the space since then?

ED: Now, it’s a commercial space on rent. But I want to just point this out. Quite a lot of people asked, “How could you have closed the space?” And you know that stuck with me. I mean even if I was teaching in Mysore, I could have just got one or two guys in the office to look after it. But yeah, these are things you only begin to think of much later. But now look, I’m well past seventy and Suman is of course very busy, but we both seem to think that hey, we must—

SG: Revive it in some way.

ED: Yeah. Give it another shot.

SG: What form it will take, we don’t know.

ED: Different kind of space, different type of programming.

SG: Exactly.

ED: Different type of structure.

NF: The urgency is still there for something more to happen in this city.

ED: It is still there because city-centric sort of projects are very few. There are some people who are doing it, good things are happening, but I think on a larger holistic level, a lot can still be done.

Retrospective as Artwork, Valsan Koorma Kolleri, CoLAB.

NF: Can we talk now a bit about the exhibitions at CoLAB? There weren’t many, five or six, I believe? You began with an exhibition by Valsan Koorma Kolleri.

SG: Yes, this was the inaugural exhibition at CoLAB. Valsan is one of those very gifted artists whose site-specific sculptural works emerge directly from the environment in which he works. His installations interact with trees, new or historic architectural structures, and urban spaces. We felt that he would be the right choice for the opening of an art and architecture gallery. His week-long residency at the gallery resulted in the exhibition ‘Retrospective as Artwork’ which played with the idea of the artist as archivist. The exhibition had sculptures, which were iterations of works that he had made earlier, both within and outside the gallery space. But the core of the show was his slideshow of photographs, which historicized his own practice as an artist through the work he had made. The exhibition drew in a lot of people and it was a really nice beginning.

ED: And the fact that it was inside and outside, created a certain dynamic. You were not holed into the space.

NF: And you followed that up with the exhibition ‘World Information City’ curated by Ayisha Abraham and Namita Malhotra.

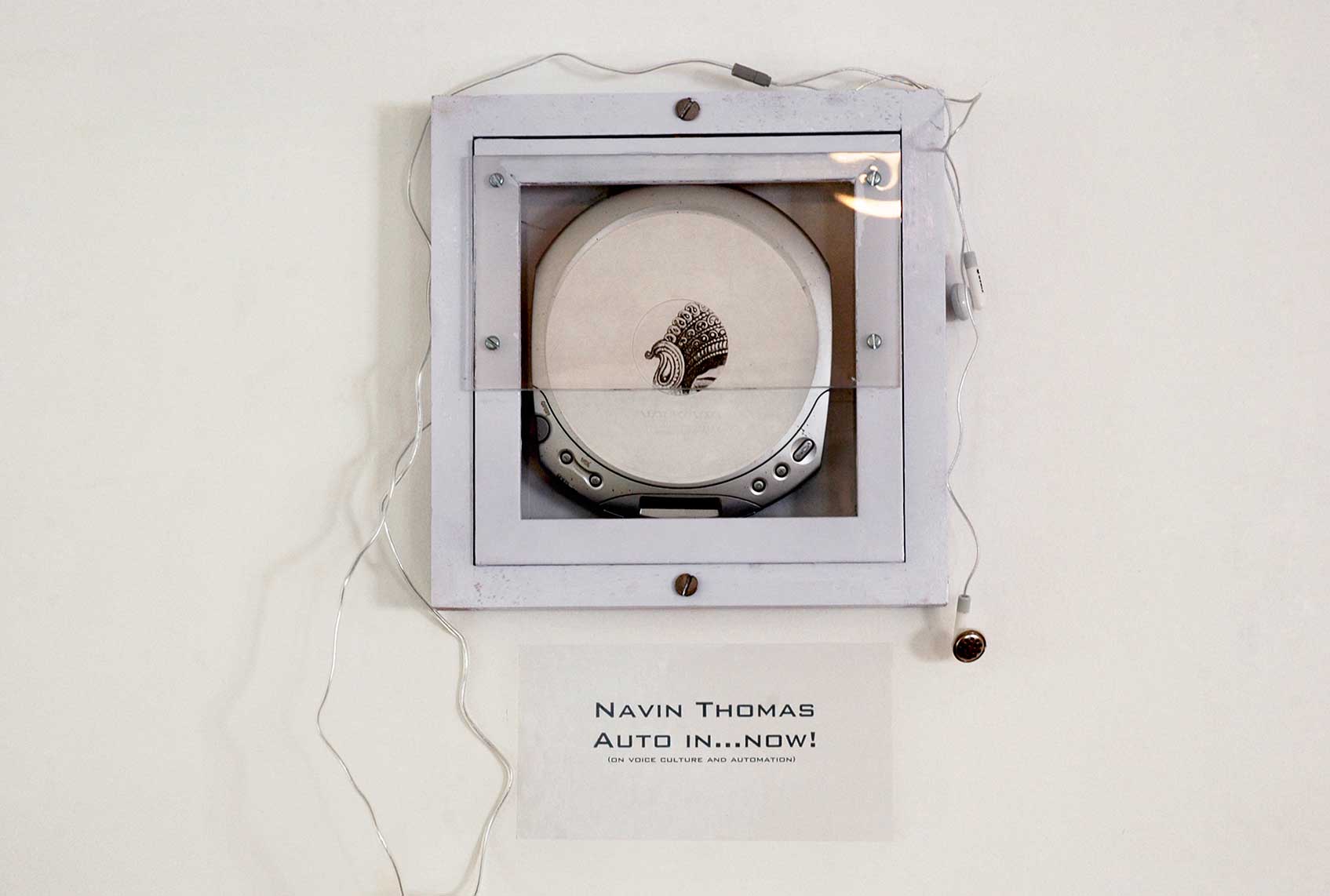

SG: Yes. One of the other objectives of CoLAB was to collaborate with people, to build up a network of artists, curators, and architects in the city. Ayisha Abraham (artist) and Namita Malhotra (from the Alternative Law Forum) were curating the Art and Media section for a large project called ‘World Information City’ which looked at Bangalore not merely as an information city, but as city with a rich past and a future that was not necessarily connected with information alone. As part of this program, we hosted one exhibition curated by them that had the works of artists Sheela Gowda and Naveen Thomas. While Naveen’s was a sound piece, Sheela’s large sculptural workSome Place with pipes and taps, mimicked the complicated grid of a city.

NF: ‘World Information City’ had many sites across Bangalore, if I am correct. It wasn’t only at CoLAB?

SG: It ran across a section of the city. You could walk from CoLAB to all these different venues.

NF: And then you had three more shows—‘City of Glass’ with Ashok Sukumaran and Christoph Schafer, ‘Around Architecture’ curated by Marta Jakimowicz, and ‘Footprints’ curated by Kavita Shah, which featured the Chhaap printmaking studio from Baroda.

City of Glass, Christoph Scfafer and Ashok Sukumaran, CoLAB.

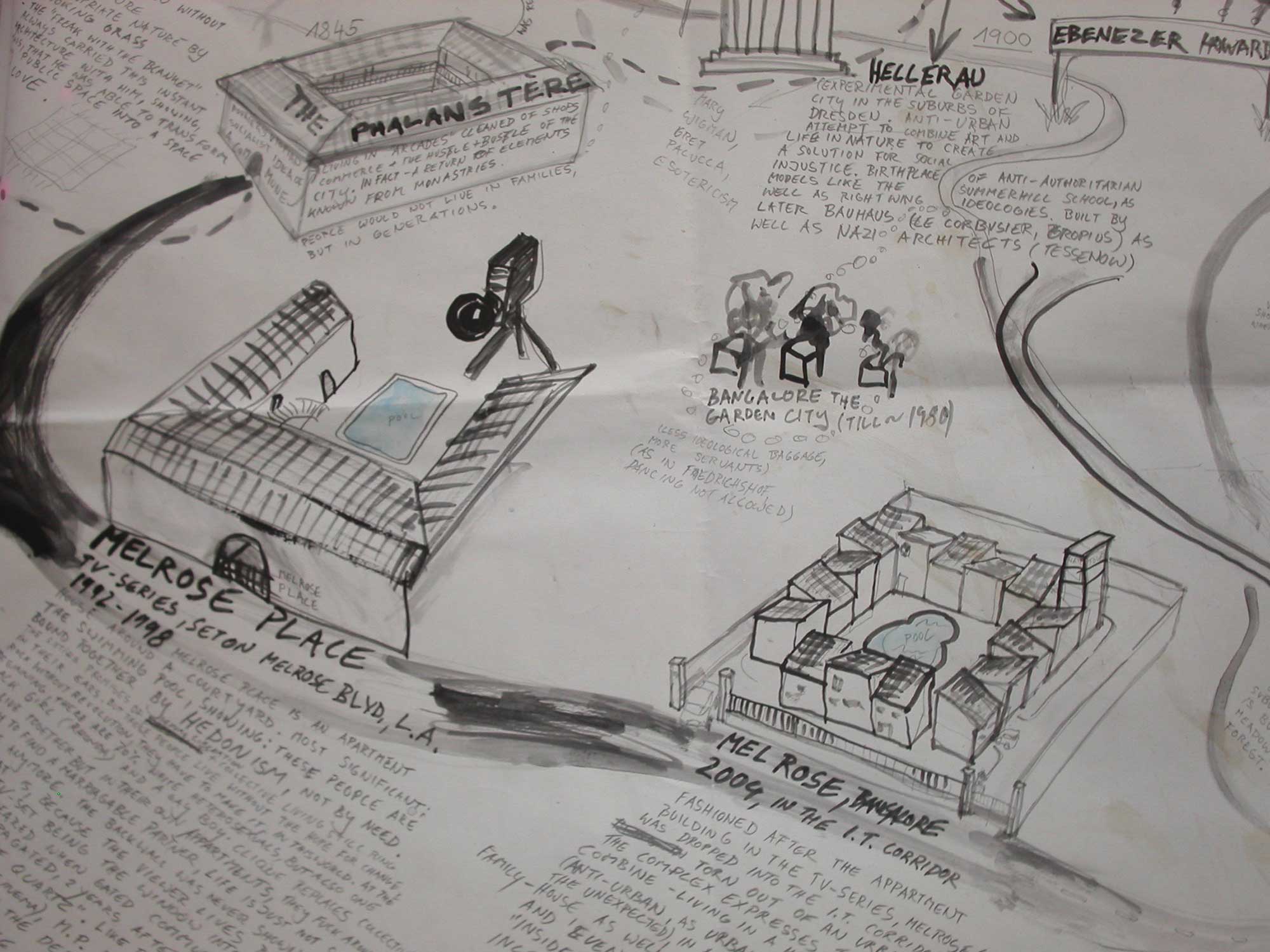

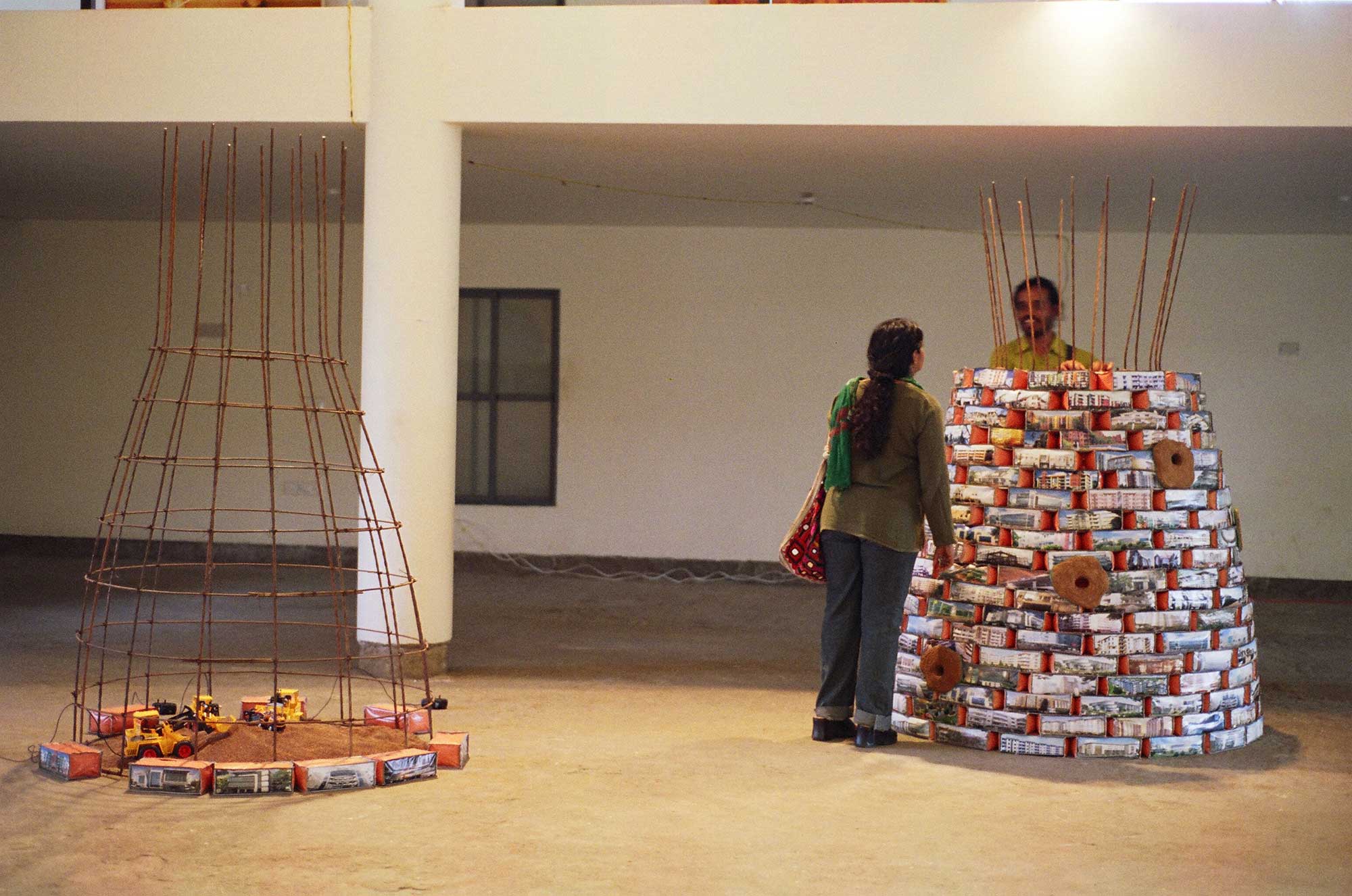

SG: Yes. ‘City of Glass’ was a natural sequel to the ‘World Information City’ show. Christoph’s (an artist from Germany) work, if I remember right, was a humorous take on the idea of the “gated community” which was just becoming popular at the turn of the millennium. Ashok was already exploring the digital, interactive mode, which is so much a part of his practice today.

‘Around Architecture’ was our first attempt at hosting and curating exhibitions and events outside of the gallery space. We invited the art critic Marta Jakimowicz to curate this exhibition in a large three-storied building called Wahab Chambers that Edgar had just completed. Marta invited nine artists and one architect. To quote from her catalogue essay, she says, “The present exhibition does not wish to pin-point the obvious recurrence of architectural motifs in art works. Rather, it aims at touching on those more elusive but enriching regions of inspiration that art owes to architecture. Consequently, the ten artists participating in this exhibition have been chosen for their ability to capture such deeper essences and connections with their impact on the human mind and heart.” The artists in the show were Avinash Veeraraghavan, Anita Dube, Ashok Sukumaran, A Balasubramaniam, Pooja Iranna, Gautam Bhatia (architect), Nasreen Mohamedi, Suresh Kumar, Ayisha Abraham, and LN Tallur. Bodhana Arts and Research Foundation from Mumbai generously came forward to fund the catalog. One thing I do remember is that we had a really eclectic audience for this show as Wahab Chambers was located in the commercial hub of the city, close to the Cantonment Railway Station.

Around Architecture, curated by Marta Jakimowicz, CoLAB.

NF: And what about ‘Footprints’?

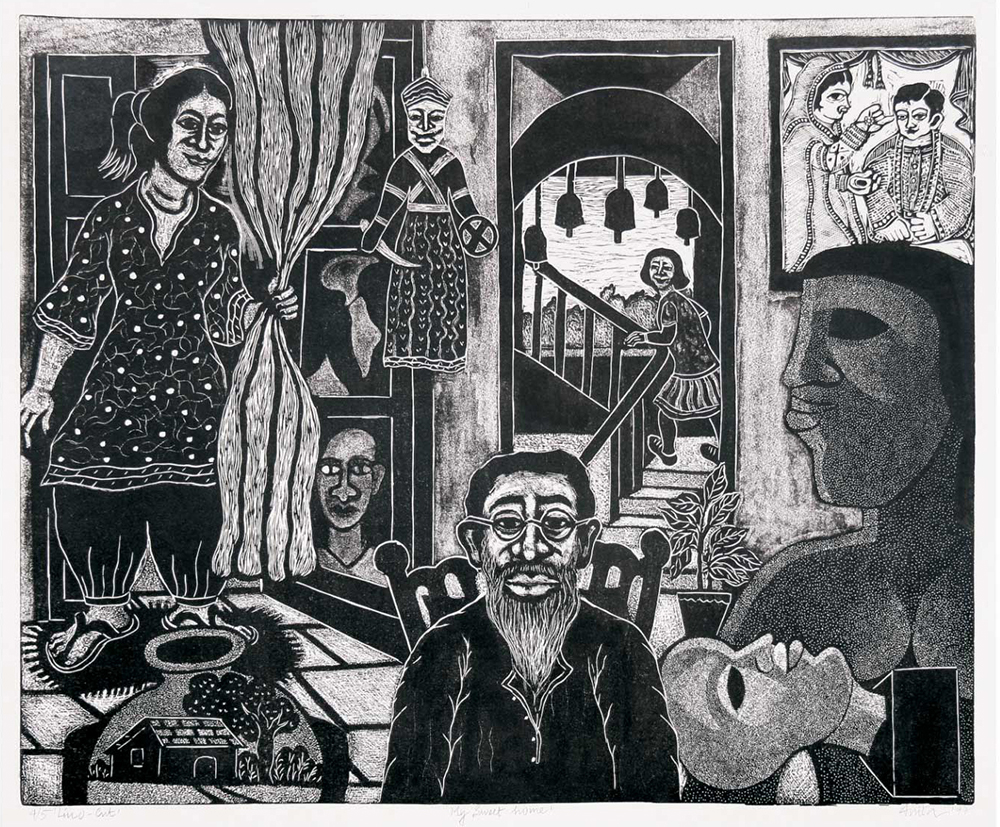

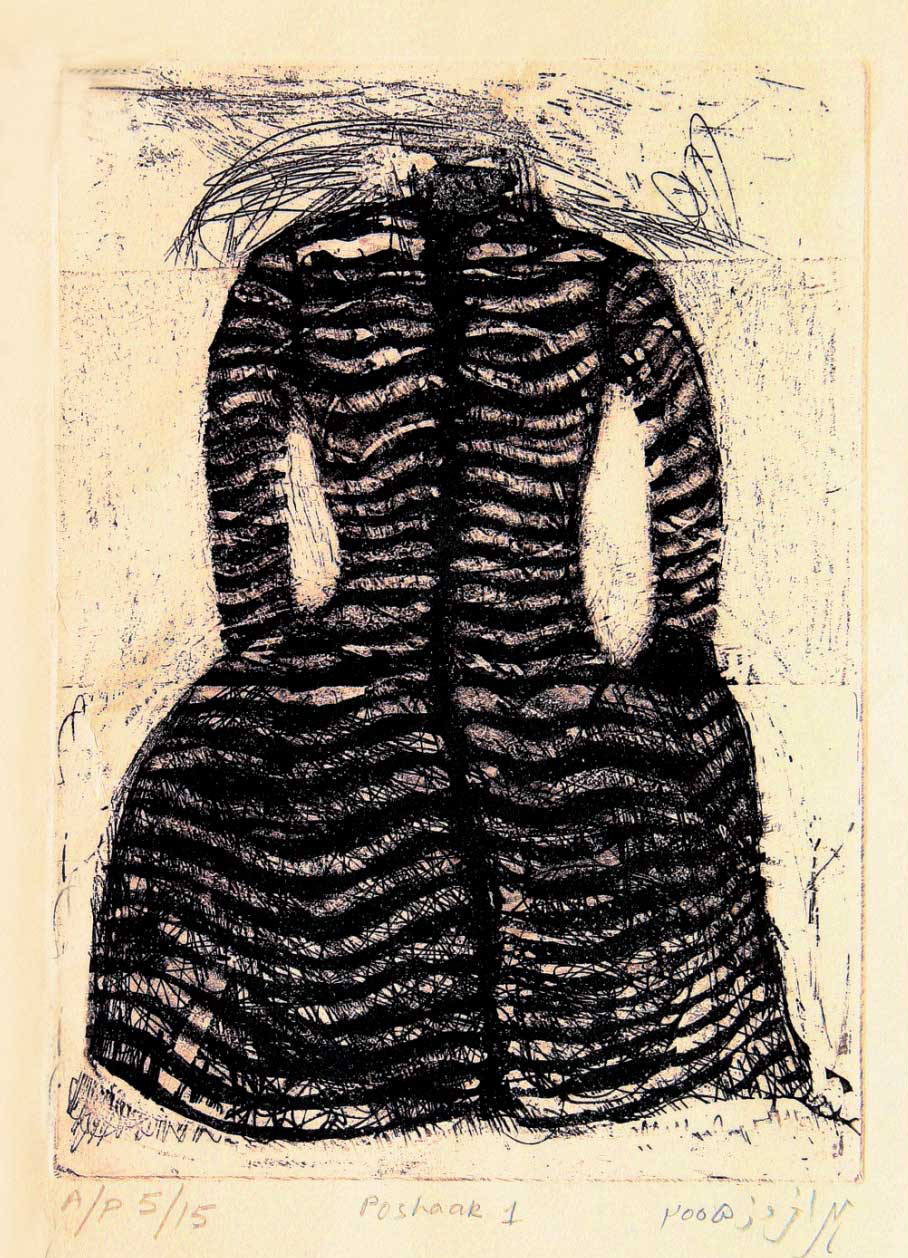

SG: ‘Footprints’ was curated by Kavita Shah, who ran Chhaap, a printmaking studio in Baroda. Chhaap was set up by three printmakers—Gulammohammed Sheikh, Vijay Bagodi, and Kavita in 1999 to promote a wider appreciation of prints and printmaking in the country. ‘Footprints’ was a very large exhibition of prints made by a group of women artists.

Besides the exhibitions I have spoken of, we also had other things happening at CoLAB—like the annual event of the Srishti School of Art, Design, and Technology which showcased the works of final year students, and other small exhibitions by local artists.

NF:Was there a curatorial focus to the exhibitions that took place at CoLAB? As in, beginning with ‘Retrospective as Artwork’ and through ‘Footprints’ was there a framework through which artistic practice was addressed across the different exhibitions? Or was it contingent upon the needs and desires of each specific show as well as the artists/curators involved?

SG: It’s been so long ago, but I don’t think we had a rigid curatorial framework. We were particularly interested in having shows that were city-centric, that looked at the city that was changing rapidly. These were the early years of the 21st century, and Bangalore was then considered to be one of the fastest growing cities in Asia. I think some of the exhibitions we had addressed these aspects either directly or tangentially. But besides a framework, it was also about extending the gallery to fellow travelers, making the space accessible to artists, curators, and architects whose work we believed in and wanted to be associated with.

Footprints, curated by Kavita Shah, CoLAB.

NF: Another big part of CoLAB was, as you mentioned, the lectures, and apart from the Goethe Institut collaboration, you were also hosting others where you had artists, architects, and academics speak. How were these organized? Were these people passing through Bangalore or were they flown down?

SG: They were all passing through Bangalore. Roger Buergel for example, gave a talk about his research for Documenta XII, for which he was in India. Dr. Jill Scott & Prof Marille Hahne—both artists and researchers at the Institute of Cultural Studies in Art, Media & Design HGKZ in Zurich—spoke about their practice; Eoghan McTigue, an artist from Berlin, did a short residency with CoLAB and spent time meeting artists in Bangalore. We also had artists from Ireland and Northern Ireland—Una Quigley, Mags Fitzgibbon, and Heather Allen. I remember Ellen Driscoll, Professor of Sculpture at Rhode Island School of Design, speaking about the ceiling of the Grand Central Terminal in New York that she had worked on in glass, metal, and mosaic. Besides visiting guests from outside the country, we also had slide lectures by local artists or by artists from India who were visiting Bangalore. And Edgar organized a whole series of film screenings, which were followed by discussions.

Banner, Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture, CoLab Goethe Lecture Series.

Banner, Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture, CoLab Goethe Lecture Series. ED: Yes, we had done a lot of that. I had a good source of films that were coming in from Holland but not always in English. It was either in German or Dutch, but we were still screening them. But to go back to your question, besides people who were traveling through the city, we also had very empathetic collaborators like the directors at the Goethe-Institut.

SG: Yes, and on one occasion the British Council also partnered with us to host a talk by the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist when he was on a research trip to Bangalore for his exhibition called ‘Indian Highway’.

NF: The collaboration with the Goethe-Institut for the lecture series was more curatorially focused. It looked at, and now I’m quoting the press release, “reconstruction and the historical turn from the perspective of contemporary artistic practice”. And it was also structured as one lecture a month, a year-long program. Could we speak about this framework?

SG: Unlike the exhibitions which didn’t necessarily fall into a rigid framework, we did in fact have a broad kind of theme for the lecture series ‘Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture’. I think this grew out of something that Grant Watson (a curator from the UK whom I collaborated with for over 10 years) and I were working on at that time. We were working on a series called ‘Re-presenting Histories’ which revolved around artists who had made significant works during their lifetime, but were not a part of the mainstream, whose work actually slipped between schools and genres. So on our part, it was an attempt at building a body of knowledge around an artist’s practice through exhibitions, seminars, and other public forums. The two artists we began with were Nasreen Mohamedi and KP Krishnakumar.

While ‘Re-presenting Histories’ looked at singular artistic practices, the lecture series focused on artists, curators, and architects whose work referenced the past either by way of content, form, or material and reinterpreted it through a contemporary lens. We organized a lecture a month, with eight artists and four architects, of whom four were from Germany. We began the series with Roger Buergel, director of Documenta XII. His exhibition dealt largely with the idea of the ‘migration of form’.

NF: Who were some of the other speakers?

SG: There was Nilima Sheikh, who spoke about her series of paintings called ‘Each Night Put Kashmir in Your Dreams’ which was informed by historical accounts, tales, fables, contemporary fiction, and poetry about Kashmir. And then there was Nikhil Chopra, whose performance and live art practice drew on both personal and collective cultural history. We had Hito Steyerl, the filmmaker from Germany whose films at that time were a mix of documentary, found footage, and fictional elements. We also had the eminent architect Prof B V Doshi, whose work extended from small houses, large housing complexes, and institutions like the IIM in Bangalore which was inspired by ‘temple cities’. Besides that, we also had others like Atul Dodiya, Amar Kanwar, N S Harsha, amongst others. Others from Germany were Alice Creischer and the architect Matthias Böttger.

NF: It’s interesting, because as you said, with the exhibition ‘Around Architecture’ you were playing with the idea of moving out of CoLAB’s space, and it was with this lecture series that this fully happened. You were using as venues sites like Venkatappa Art Gallery, NGMA, and Max Mueller Bhavan.

SG: Yes! Our aim was to use public spaces like the Venkatappa Art Gallery, that were already there, but weren’t being used much. This was a way to rejuvenate these public spaces.

ED: And our lecture series at Venkatappa was well-attended.

SG: Very well-attended.

ED: I couldn’t get in myself once!

(everyone laughs)

Audience with Edgar in 2nd row, extreme right, Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture, CoLab Goethe Lecture Series.

NF: That’s very interesting, because suddenly CoLAB becomes, from a singular site, this kind of expanded set of coordinates in the city. And somewhere this also reflects your own role, Suman, as an independent curator. That was a professional category that was really in its early days back then in India, and you were leading the way, with your projects such as ‘Re-presenting Histories’. Can we talk a little about this? Because although it’s not a CoLAB project, I think there’s links here.

SG: After CoLAB at Shah Sultan Complex closed down in 2007, it evolved into a siteless research-based curatorial program with a strategy of its own. It became what the architect Niklaus Hirsch describes as a ‘mobile institution’—an institution without its own building but which can be temporarily docked at host institutions where it can realize guest exhibitions and collaborative projects, and then move on.

The first project that I worked on under CoLAB’s new avatar was called ‘Re-presenting Histories’ along with Grant Watson. I have spoken about this a little earlier and the two artists we began work on were Nasreen Mohamadi and KP Krishnakumar. We were lucky to find support for these projects from the Office for Contemporary Art (OCA), Norway.

Unlike her contemporaries in Baroda in the 1970s who were making large-scale figurative works, Nasreen was making drawings that were formal, abstract, minimal, austere, and in a counterpoint to ‘narrative’ painting. Her work had not been shown since her death in 1990, and there wasn’t very much written about her either. So our Nasreen project took the form of a seminar and an exhibition. We organized a seminar at JNU, Delhi and the speakers were Geeta Kapur (Nasreen’s friend, art historian, curator, critic, writer), Ruth Noak (co-curator of Documenta 12, which had included Nasreen’s work), Parul Dave Mukherjee (Professor at JNU), and Nancy Adajania (curator, critic writer). Also present were a number of her friends and students. The seminar cross-referenced different memories and points of view and generated new insights about Nasreen, the person, and her work, which all fed into the exhibition that we curated in 2009 at OCA called ‘Nasreen Mohammedi: Notes’. Interestingly this exhibition travelled to eight museums in England and Europe thereafter.

ED: Wow! Was that the show with Piet Mondrian?

SG: No, that came much later. In the summer of 2014, Tate Liverpool organized a large exhibition called ‘Abstraction and the World' which included the works of Piet Mondrian and Nasreen Mohamedi. I curated the Nasreen section with a curator from Tate Liverpool called Eleanor Clayton.

ED: I still have that poster!

SG: The second project in our series was on KP Krishnakumar, the leader of the Radical Painters’ and Sculptors’ Association. This group of artists actively questioned the theoretical and political assumptions of contemporary art through a series of exhibitions, through the 1980s, staged in both Delhi and Baroda. Our project on Krishnakumar took the form of a seminar that we organized in JNU in January 2010 called ‘Questions and Dialogues: A Radical Manifesto’.Speakers included the artist Anita Dube who had written the manifesto for the Radicals in the 1980s, Will Bradley who had edited a book on Art & Social Change, Amar Kanwar, an activist-artist, and Gavin Jantjes who was compiling a new history of the art of South Africa.

In April the same year, 2010, we opened the lecture series ‘Practices in Contemporary Art & Architecture’.

NF: I think the close of the lecture series also marked the end in some way, right? These international curatorial projects must have demanded a lot of attention and time and as Edgar said, he had his practice and teaching. But I’m not sure if you ever formally closed or ended CoLAB.

ED: Yes, it didn’t close.

SG: It didn’t close. After the lecture series, it faded away, I think.

NF: But I mean, in some ways, it’s still very much alive. I noticed in Edgar’s latest book, ‘Architecture Travelogues: Drawing between the Lines’, out in December 2022, it says published by “CoLAB A+A, a virtual gallery space”.

ED: We refuse to let it die!

SG: Right!

NF: And what’s next? You guys are thinking again, that’s a good sign.

ED: We definitely are thinking. We are looking at somehow making it a little more fluid; of course how, one has to see.

SG: Yes, we have to.

ED: Put the grill on, you know!

Edgar Demello studied at the SPA in New Delhi and the TH in Delft, and thereafter worked with Prof. Wilhelm Holzbauer and Prof. Carl Aubock in Amsterdam and in Vienna. Has been in private practice for four decades. Taught at various architecture schools in the country, including most recently the RVCA. In 1985 founded, with six other architects, the group BASE. In the year 2000, opened the Architecture Gallery & Bookshop (tAG&B), a platform for inquiring into the transformative potential of other disciplines on the body of architectural thinking and practice. Seven years later it morphed into CoLAB Art + Architecture. Most recently has completed the ‘Architecture Traelogues’, a compilation of diverse forays into familiar as well as uncharted terrain. His earlier book ‘Five Architecture Fables’, that is being re-formatted for children, awaits publication. He lives and works in Bangalore and Goa.

Suman Gopinath is an independent curator based in Bangalore, India. She studied Fine Arts Administration and Curating at Goldsmiths, University of London, UK. She co-founded CoLAB Art & Architecture with Edgar Demello (2005–2011). She was Senior Programme Officer with India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) where she managed the Archival and Museum Fellowships from 2013–2022. Some of her co-curated projects and exhibitions include the Singapore Biennale-An Atlas of Mirrors (2016–17); Nasreen Mohamedi, Tate Liverpool, UK (2014); the Biennale Jogja-Equator #1 Shadowlines: Indonesia meets India(2011–12); Nasreen Mohamedi: Notes/Reflections on Indian Modernism (2009–11; this travelled to eight museums in Europe). Her most recent curatorial project was KP Reji: The Good Earth (2022–23) at the Kerala History Museum in Kochi, India. Suman has contributed texts for catalogs, magazines and journals like Afterall, Flash Art, and Art Review.

Nihaal Faizal is an artist based in Bangalore, India. In 2018, he founded Reliable Copy, a publishing house for works, projects, and writing by artists.