Models for a Suburban Art Scene

Yelahanka’s

Transient Art Spaces

Anisha Baid

Published on 10.06.23

Manasi Stationers, Nihaal Faizal, 2013-21, collection of 35 rough books used by the customers of Manasi Stationers in Yelahanka New Town (Karnataka, India) to test out their available products before purchasing.

Manasi Stationers, Nihaal Faizal, 2013-21, collection of 35 rough books used by the customers of Manasi Stationers in Yelahanka New Town (Karnataka, India) to test out their available products before purchasing. Yelahanka’s New Town 5th Phase Park is a municipal park situated across the street from the main campus of Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology (now known as Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology). In 2018, Manasi Stationers—a local stationery shop—sponsored Citrus Fest, an art and craft festival, in the New Town 5th Phase Park. Manasi Stationers is a family-owned stationery and art supply store located in Yelahanka New Town, Bangalore, that has been serving the neighborhood’s residents for almost 20 years; the students of Srishti (who are offered an official 10% discount at the store) have been one of the larger demographics of customers responsible for the success of Manasi Stationers. Thus, when the festival—devised and organized by Srishti faculty and students—needed the support of a local sponsor, the owners of Manasi became unique and befitting collaborators. The festival was put together with the support of representatives of the Yelahanka residential ward committee in order to operate on public land, and brought together students selling art prints, notebooks, bags, and jewelry together with local craft and food vendors as well as performances from the neighborhood’s dance and martial arts classes. A few years before Citrus Fest, the 5th Phase Park was the site of HaHaHa Sangha, a community action event organized by Blank Noise, a feminist initiative created by Jasmeen Patheja, a former student of Srishti. Through its various actions in public spaces, Blank Noise calls for women to occupy public spaces in leisurely and comfortable ways—sleeping, drinking tea, or laughing together. This event at the park invited an intergenerational, diverse group of women, from local domestic workers to office workers and university students, to occupy the neighborhood park and participate in a laughing club.

Yelahanka New Town is a semi-urban satellite town in the sprawling metropolis of Bangalore, and along with the rest of the city, has seen a rapid succession of changes to its demographics, infrastructure, and cultural life in the last two decades. Large office buildings and busy market streets, several schools and universities, gated residential developments, and peaceful retirement colonies all exist adjacent to each other. Distributed within this urban topography are also the freestanding campus buildings of Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, each one quite unassuming in its appearance, despite the institute being an expensive private[1] education center for art and design in the country.

White People of New Market Road, Anisha Baid, 2017. A photo essay documenting the visual culture of Yelahanka. Courtesy: Author.

White People of New Market Road, Anisha Baid, 2017. A photo essay documenting the visual culture of Yelahanka. Courtesy: Author. However, arriving as young high-school graduates from other big Indian cities, my friends at Srishti would often joke about how walking down the street in Self Financed Society (SFS)—a retirement colony that became host to Srishti students seeking accommodations—felt like traveling back 10 years in time. After passing through the heavy traffic jams and bustling market streets of the outer ring of Yelahanka New Town, one would arrive at the SFS colony where the buildings had somehow evaded being a part of the city’s ever-rising skyline. I was immediately struck by the old, large trees lining the streets of SFS, along with the many small parks dispersed along the residential colony. Yelahanka New Town is a planned neighborhood, structured in concentric semi-circles, making the streets of SFS long, winding, and labyrinth-like. In this gentle neighborhood of largely one- or two-storied houses (as opposed to the multistory apartment buildings of more urban areas), dotted with an occasional bakery serving tea and snacks, one did not mind getting lost, or sitting by the side of the road watching street dogs go about their business.

By contrast, the experimental curriculum at Srishti was outlandish in the opposite way, asking one to venture into unconventional and uncomfortable territories—often within the same neighborhood. Over the years, this neighborhood became home to many young artists and creative practitioners who have worked for Srishti or studied there. As such, it has been the site for multiple transient micro-communities of artists and creative practitioners to share space and work under self-organized structures that remained largely non-commercial. The nature of these spaces varied from extremely loose and informal to highly directed and controlled, changing based on the needs and desires of its stakeholders.

One such participant in this economy of creative spaces was Tsohil Bhatia, an artist currently based in New York. Tsohil was a resident of Yelahanka in the early 2010s and was starting to develop a durational performance practice while officially enrolled in a product design program at Srishti. Living in a large, shared house with other students—most of whom had had no exposure to performance art before—Tsohil began to invite friends and faculty into their bedroom to witness these durational performances. The works they were creating in Yelahanka were investigating the image and perception of their body, manipulated through uncomfortable processes, and often completed by the act of witnessing by an audience. Often, this would be Tsohil’s friends—assisting in covering their entire body in plaster, or carrying them to and from classes during a weeklong performance where they relinquished control of a body part each day. At one of these early gatherings in their bedroom, Tsohil asked their audience to face the wall as they proceeded to urinate on the mattress. “I had to acquire a new bed,” they recall in conversation, describing the desire to make and show art in the home and subsequently brushing up against the frictions that emerged from it. As such, Tsohil’s bedroom operated as a highly informal gathering space for a small community to witness their work.

In contrast, G.159 emerged around the same time, as a student-run apartment gallery (where Tsohil went on to do multiple performances), founded by Nihaal Faizal and Roshan Shakeel and taken forward by Nihaal in his apartment in SFS, Yelahanka New Town. Nihaal recalls encountering the model of the apartment-run gallery online, in cities like New York. Together with peers interested in making and sharing art, he decided to start hosting regular exhibitions in his living room, with opening and closing nights becoming parties often hosted on the rooftop of the building. G.159 was located on the second floor of a relatively recently constructed building in SFS with a permanently empty elevator shaft and a large garage on the ground floor. The three-bedroom apartment was occupied by Nihaal and a rotating cast of students over the course of G.159’s life. The exhibitions mostly occupied the sparse, white-walled living room, and sometimes extended to the unused small mandir (shrine) room of the flat. The door to the apartment opened into the living room, and its (conveniently) white walls were only broken by a large, blue-framed window looking into the street and at a tall rain tree outside.

In an anecdote shared on G.159’s now-defunct Facebook page, a visitor fondly recounts hesitantly taking his shoes off on his first visit to the gallery, not sure if the space had to be regarded as a regular Indian home or not. One of the earliest shows at the space describes its curatorial premise as a collection of works from “artists invited based on their proximity to the site, with three artists residing in the same building, while the others lived in the neighboring houses.”[2] In some ways, G.159’s success can be described by its commitment to building and maintaining these proximal communities—it emerged from, and relied on, the lack of any space for artistic output from the growing community of creatives in Yelahanka. In addition to its location and proximity to the university, Nihaal’s personal connections in the art community in the larger city of Bangalore brought outside audiences and artists to the neighborhood. G.159 also became a space for others to host programs like Moakshaa Vohra’s Home Theatre screening series, where she screened films in various Yelahanka PGs occupied by Srishti students, curating films in conversation with the residents—from mainstream Bollywood to experimental and archival films.

Painting of G159, Aditi Rajeev, 2015, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy: Artist, G159 and Nihaal Faizal.

My first visit to the space, in 2015, was during a collaborative performance by Meshi Sankar and Sanika Palsikar. This event was called ‘slapjack’, where the two performers dressed in grey were engaged in an intense match of the common children’s game slapjack while standing over a table. This performance was controlled by start and stop commands yelled out by the audience sitting on the floor around them. I remember leaving the space—still in my first year of art school—thoroughly perplexed by what I had seen, but excited to witness in practice the provocative idea that art did not always need pre-determined meanings or aesthetic innovations, only a particular audience. In retrospect, I was discovering ideas of relational aesthetics and the ‘everyday’[3]as conceptual frameworks for art, long before theoretically encountering them in my education.

G.159 went on to put together serious solo shows from exhibiting artists, host visiting scholars for lectures and discussions, and invite independent curators to use the space for their projects. Those who were part of this community in its four years in Yelahanka remember Nihaal’s particular professionalism in running the space—an attitude that was rather unfamiliar amongst the students but was vital in creating a consistent and vibrant continuity of programming in the gallery.

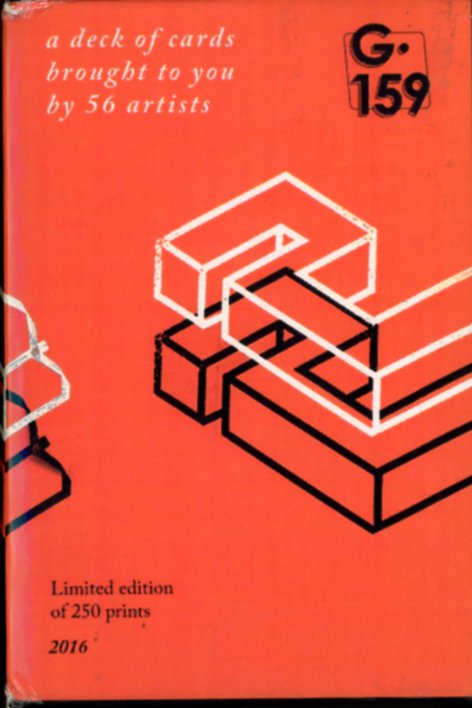

A deck of cards featuring 56 artists in Yelahanka, curated by Roshan Shakeel, released by G159. Courtesy: Roshan Shakeel. The entire deck is available at Home Sweet Home archives.

Another space that emerged alongside G.159, although far more short-lived, was ‘We’ll Figure it Out’, started in 2015 by Linda Stauffer, an exchange student to Srishti from Zurich, Switzerland. In the same neighborhood of SFS—populated by retired pensioners and college students—she started an event titled Bizarre Bazaar. The bazaar was an evening of barter exchange at the parking lot of her student apartment. Open to the passing public and publicized by word-of-mouth and on social media, the event set up a situation where people could exchange things that they had for other objects at the venue. ‘We’ll Figure It Out’ went on to host four exhibitions and performances before its dissolution at the end of Linda’s time in Bangalore. In contrast to the fairly controlled and consistent organizational model of G.159, Linda insisted on informality and a looseness of structure for the space, saying, “an artist can show work [in my gallery] that is not ready yet to show. An artist in a space like this doesn’t have to think too much, and can exhibit with less pressure and judgment.”[4]

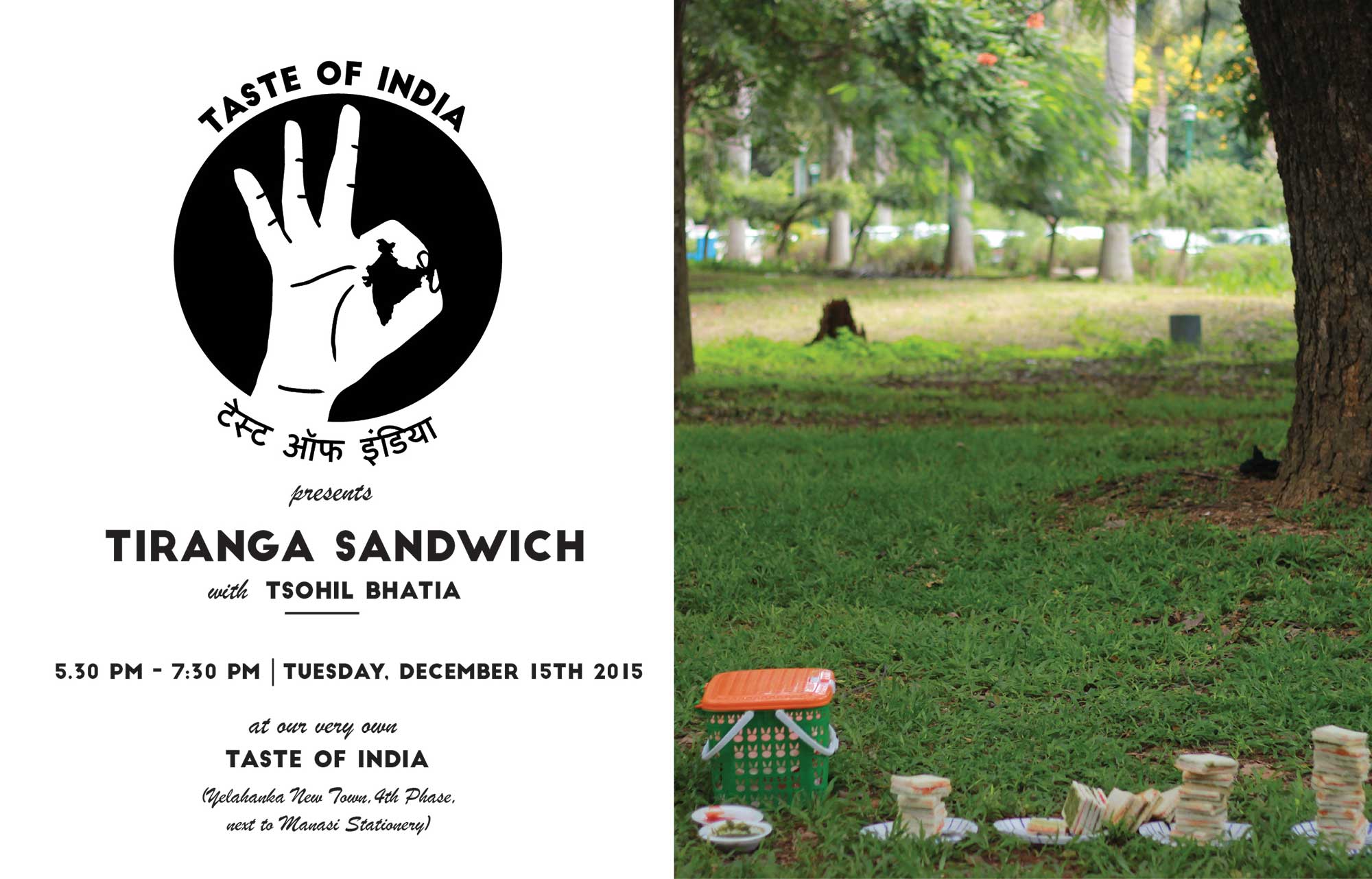

In her essay about alternative galleries in Bangalore, Alison Byrnes notes that “one function of the home and informal galleries has been to offer access to the system to artists who had not yet entered it.”[5]In addition, informal exhibitions also offer access to an uninitiated audience. Gavati Wad’s curatorial project Taste of India created an exhibition space at a local Yelahanka eatery named Taste of India. Having frequented the restaurant and developed a relationship with its owner Amod Kumar Bhutiani, Gavati wanted to explore the potential of encountering art in an informal and everyday setting, as opposed to in an art gallery or museum. “I realized that our country is in a very interesting phase politically, socially, and economically but we are not talking about it. How does art facilitate a dialogue on patriotism, national identity over a meal was something I wanted to explore,” she said in a newspaper article[6]from this time. In retrospect, the project was quite timely in interrogating popular generalizations of what India meant, as nationalistic imagery in the country has been undergoing a concerted revision and revival under the Hindu right. The restaurant was initially located in a smaller ground-floor commercial space and then shifted to a larger shop right outside the Yelahanka New Town bus depot; it served largely North and West Indian dishes and was most appreciated for its Punjabi-style stuffed paranthas. Through these two iterations of the restaurant, it was furnished with plastic chairs and tables and decorated with flex-printed images of popular North Indian dishes, from dahi vada to kadhai paneer, and the Taste of India exhibitions worked with these aesthetics, incorporating cheaply printed posters, menu cards, and tablecloths as part of the exhibition.

Poster of the show Tiranga Sandwich by Tsohil Bhatia, Taste of India. Courtesy: Gavati Wad

Poster of the show Tiranga Sandwich by Tsohil Bhatia, Taste of India. Courtesy: Gavati WadAlongside these alternative gallery models, Yelahanka also became the site for public exhibitions like Drive by Video—a public video art show organized by Smriti Mehra, Leslie Johnson, and Siddhanth Shetty in the garage of a commercial building on New Town Main Road. The garage was divided into seven individual, open rooms that faced the main road, with each one displaying a different (often silent) video work. The exhibition was visible to, and attracted, an audience of passing pedestrians, alongside dedicated visitors from the art school and elsewhere. The organizers of this show invited various faculty at the institute to use the space to show videos, with some choosing to display their own work, and others curating their peers’ works to be exhibited.

G.159 hosted its last exhibition Final Review in April of 2016—a year that marked the exit of many of the engaged organizers in Yelahanka. However, G.159 had demonstrated the possibility and potential of an exhibition and performance space in Yelahanka, which in turn had already inspired newer residents of the neighborhood to create their own. Partly Purple was a home gallery and project space run by Avnit Singh, with support from friends and peers from 2016 to 2018, and then became an independent curatorial project for Avnit after her time in Yelahanka. Named after the purple walls only partly repainted by Avnit, Partly Purple became a gathering space in the small bungalow she rented on one of the main streets in SFS colony. The first few projects and exhibitions at the space were class engagements and exhibitions, spilling over from the educational institution to occupy the home. In conversation, Avnit recalls how there was no space to show or share work outside the classroom in Srishti. The space went on to host various solo exhibitions, sell works, as well as host music and sound performances. The organizational work was supported by a community of friends and exhibiting artists, who were given the freedom to transform the space as they desired. One of Avnit’s desires for the space was to connect with a local audience outside of the school of art, as she personally invited neighbors and their families to visit their shows and installed posters around local shops to bring in anyone curious about the work.

While multiple factors contributed to this richness of independent activity around art in Yelahanka, much of this organizational work was taken on by a closely connected group of people relying on and inspiring each other to continue. Much of this work was also largely self-funded and conducted with very little overhead costs. G.159 organized a fundraiser amongst Srishti faculty to buy a second-hand projector for exhibiting video and digital works, while drinks and snacks were often provided by a rotating group of friends and supporters. In a similar vein, Partly Purple invited their visitors to contribute funds and raised some money during their first few exhibitions, which Avnit notes was enough to allow them to buy tea and snacks for subsequent events.

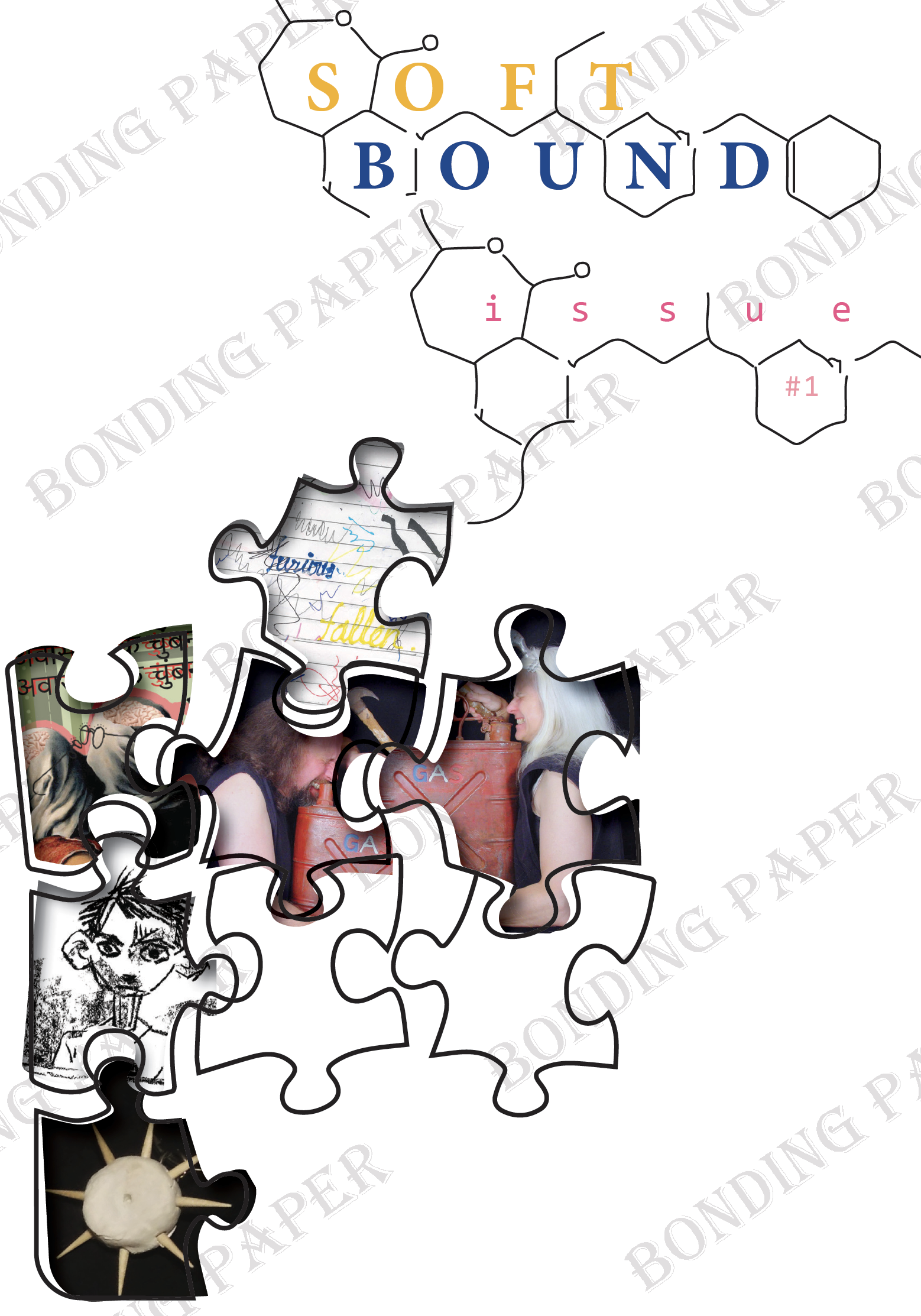

In addition to exhibition spaces, artists living in Yelahanka often opened up their own homes as temporary exhibition and gathering spaces, like Kaldi Moss, who was working with mycelium and created durational bio-art experiments in their backyard. At the end of my time at the art school (2019), I also started a publication project, compiling works made collaboratively from this network of artists in Yelahanka into a zine called Softbound, which was launched with a collaborative rug-making party at my residence in SFS. This publication was printed on copy paper on Srishti’s university printers, utilizing the remainder of all the contributors’ complimentary printing budgets provided by the institute, thus limiting the costs to only printing and binding the books. This event and zine marked for many of us the end of our time in Yelahanka, and much of the works featured familiar locations and memories from the community.

Cover of Softbound, edited by Anisha Baid. A digital copy of the zine can be found in the archive section. Courtesy: the author.

Various other projects have emerged and continue to function in Yelahanka since, including Firki, a student-run activity group, as well as MUJO, a collaborative space hosting workshops and performances and other events for the student body at Srishti. More recently, Self Financed Studios, started by Debanshu Bhaumik and Aditya Narula has emerged in Yelahanka, conceptualized as an ongoing series of events for artists to share their work. Their first edition involved an open studio event where the artists opened up their studios in Yelahanka for community conversations.

Collected together, these distributed events, happenings, and spaces serve to document the creative life of a scattered art community over many years in Yelahanka. They also offer multiple alternative models to the often-inaccessible standard of gallery exhibitions as outlets for art, and serve as examples of self-organization by artists. The city of Bangalore has also witnessed this kind of self-organization on a larger scale over the last decades, with many emergent, alternative spaces like 1Shanthiroad, Jaaga, BAR1, and Samuha existing for varying lengths of time.

Harini Kumar, in a report on the emergence of ‘alternative’ art spaces in Bangalore reflects on this city-wide economy of non-commercial spaces and asks an important question about alternativity (alternative to what?) in the context of art spaces.[7] In the more local context of Yelahanka, these spaces perhaps remained alternative to the more commercially driven gallery circuit as well as to the more popular art discourses at larger culture venues (like the Goethe Institute) or museums.

The particular nature of Srishti and its experimental pedagogical system also contributed to this emergent network of spaces. However, this was not through the direct support or involvement of the institution, but often through associated faculty (including Smriti Mehra and Leslie Johnson previously mentioned in this article) who organized, supported, and participated in this network. This alternative circuit existed in parallel to the official teaching structures at Srishti, and often filled in the gaps in its art-adjacent pedagogy. Members of this dispersed community often observed the lack of a culture of exhibitions or open-ended discussions around work, as was common in more traditional fine arts universities in the country.

Chinar Shah, the editor of this publication and former Srishti faculty who showed work at G.159 and also runs an apartment gallery Home Sweet Home says, “…it was nice to have a space to connect with artists outside of the institutional setting.” In spaces where students worked collaboratively and exhibited alongside faculty, the hierarchical structure of art education began to break down to allow for more generative and critical responses to work. Various faculty at the institute also led projects situated in the neighborhood, from Amitabh Kumar’s mural paintings projects to YellaBanni—a month-long engagement with the neighborhood through exhibitions and performances led by Sudebi Thakurta, Vipin Bhati, Narendra Raghunath, and many others. In many ways, these spaces and gatherings were symptomatic of a distributed art school—one without a unified campus or student housing. In response, parallel housing networks of PGs emerged in the neighborhood that were all within walking distance of each other and the school. In addition, many first-year ‘foundation’ courses at the school (at least during my time there) insisted that students exit the classroom and engage with the built environment and communities in Yelahanka.

Students from all over India came to Yelahanka to learn to be creative practitioners. I could observe during my time in Yelahanka that students were often blind to the significant class and language differences that existed between Srishti students and the people they would interact with (local domestic workers, shopkeepers, government workers). Since community engagement is a major aspect of art and design education, these divides sometimes played out loudly while some other times they were bridged. The rise of right-wing ideologies impacted the lives of students at times and resulted in various kinds of student organization in protest of this as well. This divide—between the larger regional and national politics, and the insular community of artists—had to be constantly negotiated whether in the classroom setting or in the creation of independent initiatives. It will take another study to analyze the impact of the complex network of education institutions and the migration of young students to a once-quiet suburb. However, it would be key to understand the impact of these activities, be it institutional or self-organized, on the immediate community of Yelahanka.

The characteristics of the neighborhood of Yelahanka, and in particular SFS as a retirement colony, also created a unique setting for these spaces to emerge. Being located a few hours away from Bangalore’s other art spaces created the desire for more accessible (in terms of distance) and local art economies, leading to a model of suburban self-organization. The combination of low rents, old quaint retirement houses, and lush, tree-lined streets protected by zoning laws in SFS created an environment that felt strangely liberated from the speed and debris of the urban metropolis. There was a sense of quiet that many of us, who have since moved out of Yelahanka and into cultural hubs, hold a deep sense of nostalgia for—even as Yelahanka and SFS continue to be rebuilt with major construction projects, flyovers, and commercial establishments.

In the contemporary art world, where large cities and gentrified neighborhoods serve as major hubs for the arts, this kind of model of local self-organization might offer a parallel (rather than alternative) strategy for artists wanting to build a critical community. The limited opportunities and institutional support structures (state-sponsored and privately funded) for artists often lead to a state of looming economic precarity, as well as a perceived social vacuum within which the lone artist must continue making work. While this model of community organizing doesn’t necessarily offer viable economic models—with most of them functioning at minimal costs raised through personal funds—it can offer ways of fostering artistic discourse within these limited means. Furthermore, institutions by their very nature, can often only allow for a controlled, highly mediated, and dominant discourse to emerge, whereas artist-run curatorial practices often become a challenge to these modes, offering the possibility of hyperlocal discourse and spaces for informal gathering.

[1] State-funded universities in the fields of art design remain limited in India, with one national design school (NID), one school dedicated to fashion (NIFT), and the famous Indian Institute for Technology having started a few design programs in the last decade. None of these institutions incorporate art education alongside design and technology, and in themselves, remain limited in providing seats and opportunities to serve the growing interest in art and design education in the country.

[2]G.159. “Lost Thoughts and Found Ideas - G.159.” https://g159.tumblr.com/2.

[3] See Certeau, Michel de. 2011. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. 3rd ed.

[4] Byrnes, Alison. 2016. “Gallery as Practice: Informal Art Spaces in North Bangalore | Unbound.” Online Journal. Unbound Journal. Accessed March 6, 2023. http://www.unboundjournal.in/home-galleries/.

[5] Byrnes, Alison. 2016. “Gallery as Practice: Informal Art Spaces in North Bangalore | Unbound.” Online Journal. Unbound Journal. Accessed March 6, 2023. http://www.unboundjournal.in/home-galleries/.

[6] Tripathi, Shailaja. 2016. “Not Playing to the Gallery.” The Hindu, February 13, 2016, sec. Metroplus. https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/not-playing-to-the-gallery/article8233737.ece.

[7] Emergence of ‘Alternative’ Cultural Spaces in 21st Century Bangalore and their Engagement with the Visual Arts by Harini Kumar, Unpublished Article.

Anisha Baid is an artist and writer from Kolkata, India, currently based in Pittsburgh, USA. Through her practice and research, she is investigating the intersection of computer interfaces, corporate culture, and gendered labor.