Karnataka Kalamela

Its Origins and Impact on the Art Scene in Karnataka

Ravikumar Kashi

Published on 15.04.2023

![]()

Between 1980 and 2003, artists from Karnataka came together and organized seven Kalamelas (art festival) in one of Bangalore’s landmark spaces, Venkatappa Art gallery, as well as a Kala Yatre, a statewide touring exhibition, in 1984. This article is a brief introduction to those events which changed the course of visual arts in the state.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a time of intense reflection, fervor, and activity in the fields of visual art, literature, theatre, and cinema in Karnataka. The post emergency optimism was lingering and there was a pronounced surge in new kinds of ‘pro-people’ politics and thinking. The air was charged with the ideas and philosophies of Ambedkar, Ram Manohar Lohia, Ramaswamy Naikar, and Jayaprakash Narayan. There was a dream of change, and an urge to create bridges between art and society because it was felt that arts were moving away from the public, and without a public, art had no meaning.

In the sphere of literature, the Dalit movement, which was garnering momentum through the 1970s began to create an impact. In 1979, the Kannada Sahitya Sammelana, chaired by the famous poet Gopalakrishna Adiga, was held in Dharmasthala. Before the event, Chenanna Valikar, a Dalit writer, had written to the Kannada Sahitya Parishath president Ham. Pa. Nagarajiah to hold a session on Dalit literature. Nagarajiah refused to accommodate a session on Dalit literature in the Sahitya Sammelana, stating there was no Dalita (downtrodden) or Balita (well-to-do) in literature. By way of protest, a huge gathering and a seminar of the Bandaya (revolution) Movement was held in Bangalore in March of the same year. This ushered in an era of unheard voices from Dalit and oppressed communities being heard for the first time. It challenged the long-held notions about literature and questioned caste hierarchies. Similarly, the Samudaya theatre group was spreading its wings and reaching out to people through street theatre. Girish Kasaravalli and others were experimenting in cinema and ushered in a new wave of ‘art cinema’. There were changes sweeping the visual arts field as well. When seen in this broader framework, the Kalamela and Kala Yatre events, held by visual artists coming together as a community and reaching out to other artists and the larger public, assume historical significance. They enabled artists to share their novel ideas with other fellow artists and changed the course of modern and contemporary art in Karnataka. Understanding the context also demonstrates how these events did not happen in a vacuum, but rather the spirit of the time shaped their actions over these two decades.

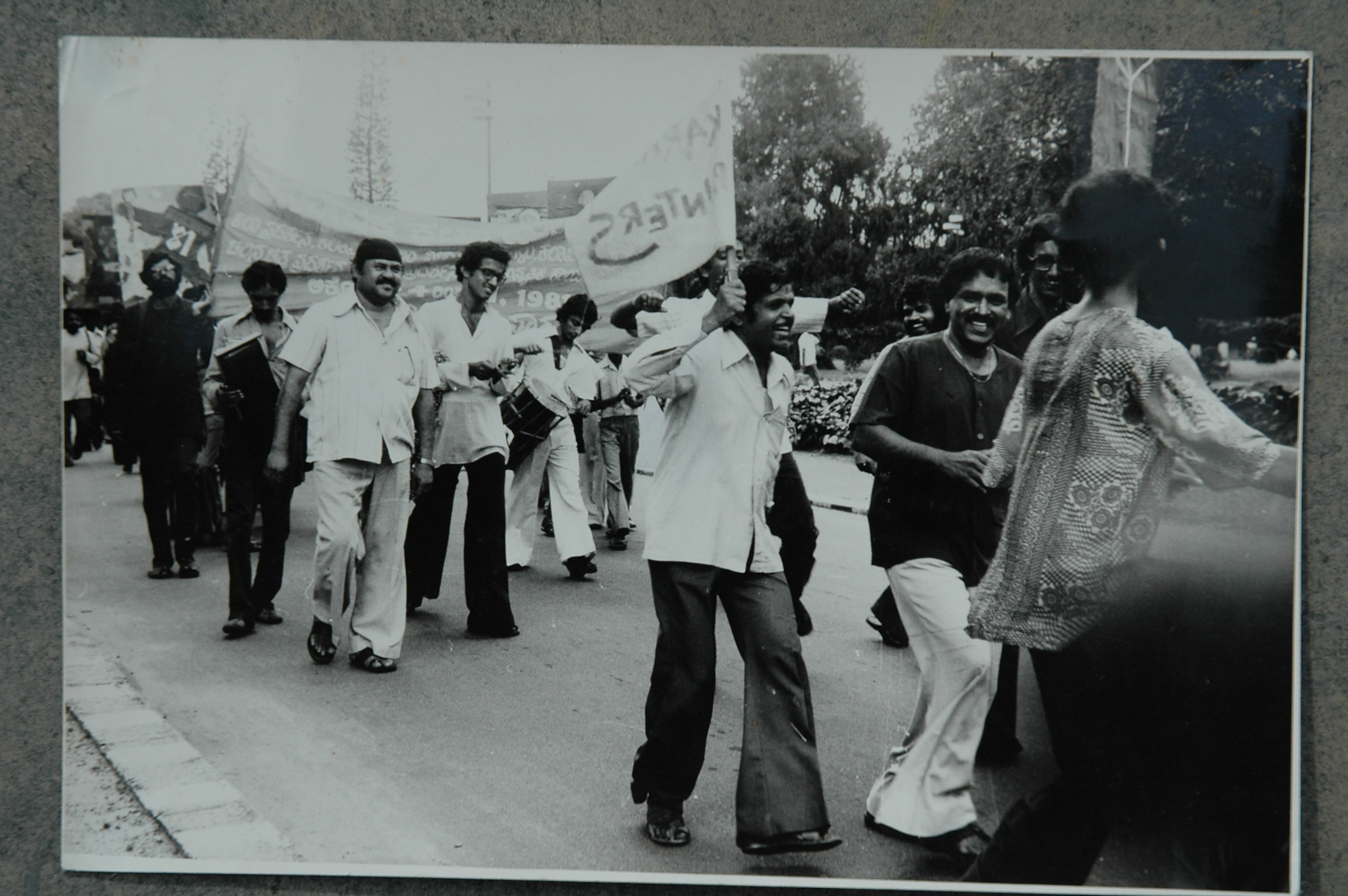

1981 Kalamela, Inaugural procession, G.S. Shenoy, G.Y. Hublikar, Ramesh Rao, Chi Su Krishna Shetty, and others can be seen in the photograph. Image courtes: G.Y. Hublikar, A.L. Narasimhan, and Ravikumar Kashi

1981 Kalamela, Inaugural procession, G.S. Shenoy, G.Y. Hublikar, Ramesh Rao, Chi Su Krishna Shetty, and others can be seen in the photograph. Image courtes: G.Y. Hublikar, A.L. Narasimhan, and Ravikumar KashiVarious factors contributed to create a conducive atmosphere for the Karnataka Kalamelas to occur. In 1978, the nationally recognized artist and Padma Shri awardee, K. K. Hebbar, became the Chairman of Karnataka Lalitakala Academy. In order to energize the moribund Karnataka art scene, he decided to give scholarships to students who wished to study in Vishwabharati University, Shantiniketan, and MS University, Baroda. C. Chandrashekhar, Chandranath Acharya, Shyamasunder S., Ramdas Adyantaya, Sheela Gowda, Marishamachar, and Kamalakshi were some of the early recipients of this opportunity. Yusuf Arakkal and Krishna Setty went to work in Garhi studios, Delhi, under the same scheme. This one move by the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy under the leadership of K. K. Hebbar changed the direction of art in Karnataka and had a domino effect; its repercussions can be felt to date.

Those artists who went to study outside the state in these reputed institutions were exposed to new kinds of art and new ways of thinking. On returning to Bangalore and other cities of Karnataka, they started sharing their experiences and a new vision with fellow artists. From this lot, a couple of artists came together and decided to hold a Kalamela. The shape and scope of the Kalamela was determined by intense discussions held with each other and with people from other fields. They dreamt of a gathering—a festival where artists can come together overcoming creative and other differences of opinion. This imagination of coming together for a larger cause was not only of individual artists but also of various artist groups from across the state (see Annexure 1). For every Kalamela that was held it was decided that souvenirs would be printed. It should be noted that in the souvenirs of the initial editions of Kalamela, the artist group names were prominently printed on a separate page, but after the third edition, they were only mentioned in the editorials, suggesting that those group identities were temporarily subsumed in the Kalamela identity as the editions progressed. In addition, for each edition of the Kalamela, different artists took the responsibility of becoming president, secretary, and treasurer. This ensured that the Kalamela did not stagnate, and each edition saw a fresh surge of energy, ideas, and enthusiasm.

It is not that these artists were inventing the idea of a Kalamela from scratch. In 1978, a Rashtriya Kalamela was held in New Delhi along with a Triennale, organized by Lalitakala Academy, Delhi. Many artists from Karnataka who visited the Triennale and Rashtriya Kalamela in Delhi felt that the Kalamela model could be replicated at a smaller scale in their home state by local artists coming together. Even before these, there were events such as the Fine Arts Faculty Mela held in MS University, Fine Arts campus (started in 1961), and the Nandan Mela held in Vishwabharati, Shantiniketan (started in 1973), which some of the artists had experienced while studying in these places. In both these melas, the visiting public mingled with the artists, which created a new kind of viewership. Artworks, prints, toys, and crafts were created by students and staff working together especially for this occasion and sold at affordable prices.

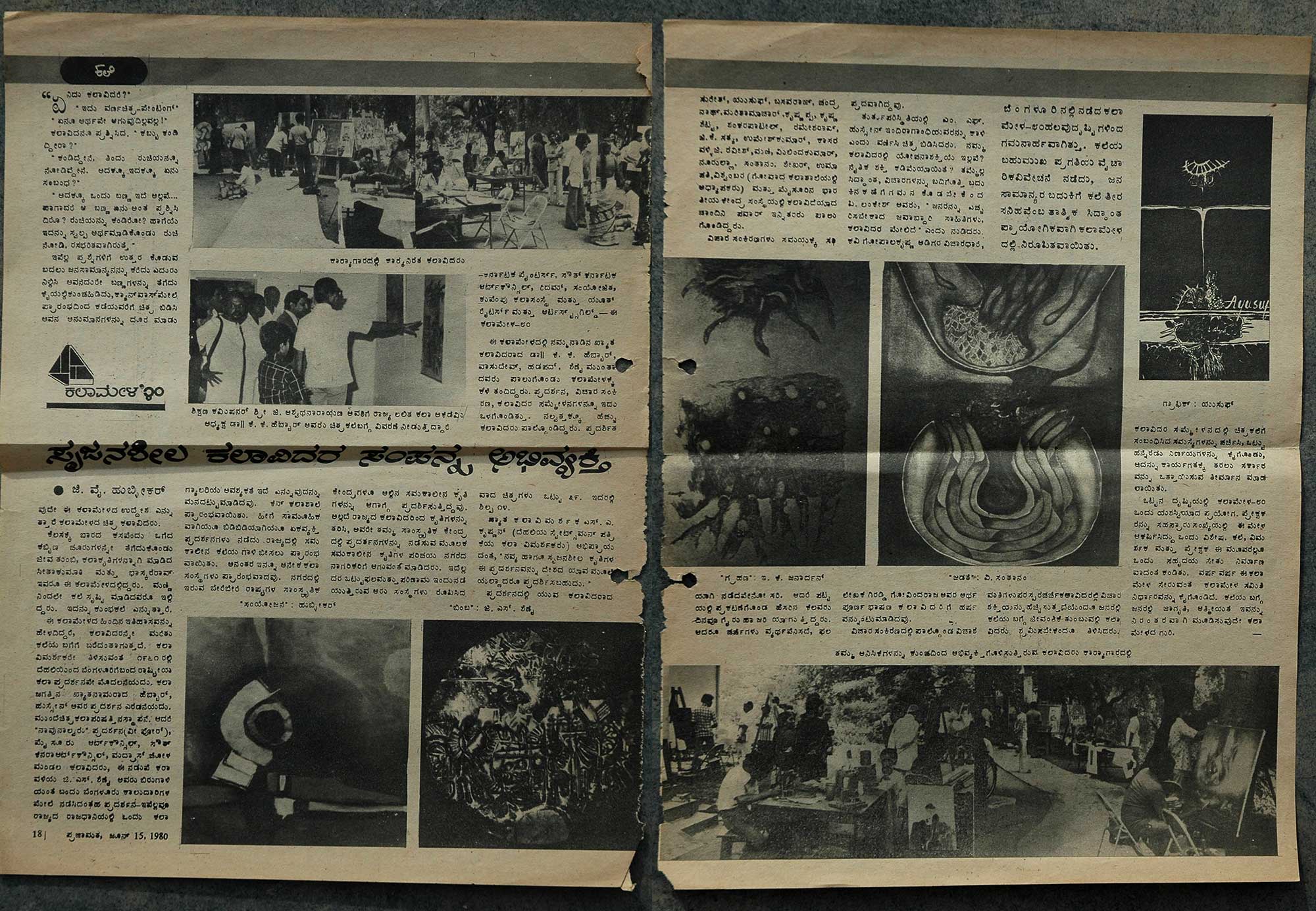

Creative Artists Expression in Abundance, .Y. Hublikar, Prajamata, 1980. Image courtesy, G.Y. Hublikar, A.L. Narasimhan, and Ravikumar Kashi

One of the reasons for establishing the Kalamela, as stated by the organizers in their published souvenirs, was to disseminate their newly acquired sensibilities and visual language with other artists of the state. Slowly but steadily, new ideas about art started spreading through the Kalamelas to the entire state. The number of artists attending each edition of the Kalamela kept increasing, from 50 artists in the first edition to 325 artists in the sixth edition. Attending the Kalamela became part of an artist’s calendar, and more than the tangible results, it was the festive mood and camaraderie, a sense of ownership, and a feeling of belonging to the larger community that was the highlight. Hence, the Kalamela grew to become the epicenter for disseminating and exchanging new dreams, ideas, and awareness among artists as well as the larger public and audience. It transformed the art practice of an entire generation and more.

It was no coincidence that the artists chose the Venkatappa Art Gallery (VAG) as the site of the Kalamela, given that the Venkatappa Art Gallery came into fruition because of artists’ pressure on the Karnataka government to create a space for visual arts in Bangalore. In 1967, Chief Minister Nijalingappa had laid the foundation stone to build the Venkatappa gallery, but the project got delayed. In 1971, artists G. S. Shenoy and others held an exhibition on the footpath of Mahatma Gandhi Road, in front of Bible Society, to draw the attention of the government to the lack of spaces for proper exhibitions. The Venkatappa Art Gallery was finally completed in 1975. It is a space that defies the conventional definitions of a museum, because it contains both the permanent collection of artist Venkatappa’s work on the ground floor, as well gallery spaces in the upper floors for contemporary artists to hold their exhibitions for a nominal rent. Before the VAG came into existence, it was the corridors of the Ravindra Kala Kshetra that used to be the site of such exhibitions. For decades before private galleries came up, VAG was the only space where artists could exhibit, gather for discussions, and feel a sense of belonging and ownership. It was also where many artists from Karnataka had their first solo shows. Unlike a museum, which is a space you arrive at after a substantial career, VAG is a space for beginnings in the history of Karnataka’s art scene. Since there are no strong rules governing the space, it is fluid, and can accommodate different kinds of activities, views, and experiments. In this sense, VAG was the most ideal space for the Kalamela, as it was the beginning of a new wave in Karnataka.

The Kalamela was not only a forum for artists to come together but was a platform for reaching out to other disciplines as well—many prominent writers, filmmakers, theatre personalities, and thinkers visited, spoke, and exchanged their views during the discussions, seminar sessions, and evening performances. The first edition of the Karnataka Kalamela, which was held in 1980 at the VAG, was a week-long affair. On the first day, there was a procession accompanied by music and dance and a formal inauguration. The events during the week included exhibitions of participating artists’ works, artists’ camps, live demonstrations by senior artists like M. F. Hussain, K. K. Hebbar and others, slide lectures, panel discussions, and seminars in the day, and theatre and dance performances in the evenings. On the last day of the Kalamela was a valedictory function followed by a communal campfire. The first Kalamela was attended by 50 artists, and it went on to attract more and more artists in its coming editions; seven Kalamelas were held, in 1980, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1993, and 2003 (see Annexure 2). In the last edition, the duration was reduced to four days. From the fourth Kalamela onward, parallel exhibitions were organized in some other institutions like the Alliance Française, Max Mueller Bhavan, and the private Krithika Art Gallery.

As mentioned earlier, after each edition of the Kalamela, souvenirs were published. These published souvenirs are historical, without which it would be impossible to reconstruct these rich layered events. Each souvenir had details of what conspired during that edition, including guest lists, participating artists’ names, details of seminars held, articles related to art, and advertisers who supported the event (see Annexure 3). Artists were involved in creating the logo and cover page of the souvenirs as well as the mementoes and memorabilia such as bags with the Kalamela logo that were distributed to the participants in later editions.

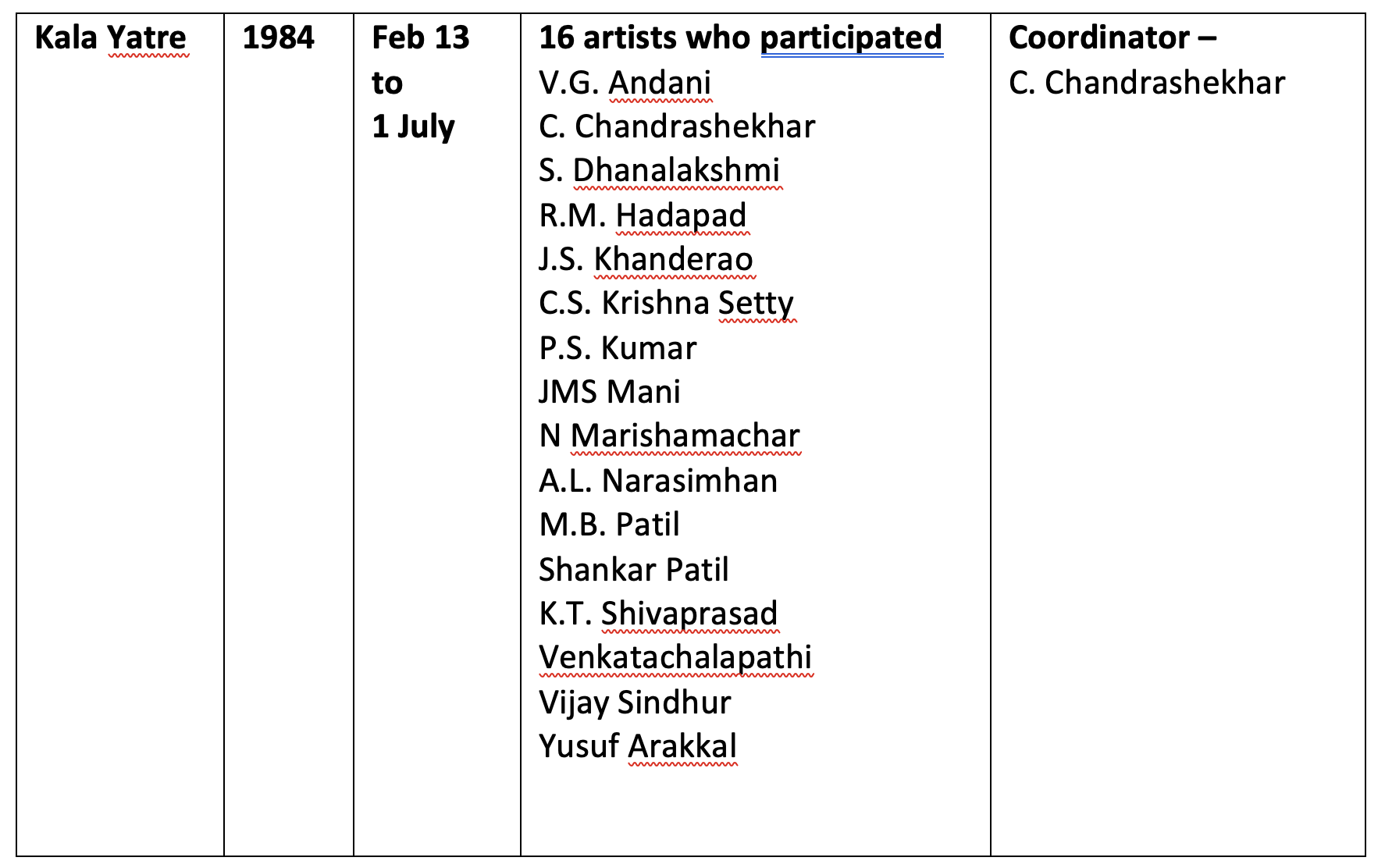

Apart from the Kalamelas, a Kala Yatre was organized from February to July 1984, which literally means ‘art tour’, which also stemmed from similar concerns of reaching out to a wider public especially in interior Karnataka. Sixteen artists, many of whom were also part of the Kalamela organizing committee, decided to showcase their work in this touring exhibition. Normally artists like to go to bigger cities like Mumbai, Delhi, or New York to exhibit because this offers them the scope to broaden their career horizons. But the desire of these artists to reach out to the public from their own state was so intense that they decided to tour the state with an exhibition of over 50 works. For six months the exhibition toured 28 places in different parts of the state (see Annexure 4). In every place, they had to unpack the works and display them, and after exhibiting for a few days in that place it was time to move on. Not every place had a proper gallery, so they used makeshift places like school corridors or halls as improvised display spaces. Along with the exhibition, they held slide lectures, discussions, and demonstrations. Artists from around the place, students, art lovers, and curious onlookers visited these shows. In some places local artists and art lovers helped them with various kinds of support, while in many other places they had to fend for themselves. The Kala Yatre was a truly one-of-a-kind initiative in terms of its ambition to reach the public in interior regions of the state.

It has to be noted that the Kalamelas or Kala Yatre were not government-sponsored or academy-directed events; they were entirely artists’ initiatives. Getting funds for organizing the events was therefore always a challenge. The Kalamela committee comprised of some freelance artists and others working in full-time or part-time jobs. There were hardly any sales of artworks of even the well-known artists, and for the others the salaries were not high. There was no major sponsor from any corporate house or public sector company. The artists had to tap into their personal networks to gather support for this initiative, reaching out to medium-level businesses, an occasional bank, and friends who supported the activity. Many a time, artists spent from their pockets; on a few occasions, printers and suppliers gifted in kind. When M. F. Hussain or K. K. Hebbar completed a painting during the Kalamela and gifted it to the organizers, those paintings were sold to collectors and the sale money was used to continue the work. Government advertisements were only a minor support, and it was the sheer passion and voluntary involvement and hard work of innumerable artists that sustained the Kalamela edition after edition.

It was not that during the heydays of the Kalamela, every artist or artist group from the state became a part of it. In fact, there were other attempts by different groups to hold similar events. The Kalamahotsava (Art Festival) organized in Chitrakala Parishath, from 22–27 January 1984, was one such art festival, but this was organized only once. It also had an artist camp, several panel discussions, and seminars, but many more art schools seem to have participated in this event than professional artists groups (see Annexure 5). A few Kalamelas and a Kalamahosatva were held at the district level. Lalitakala Academy also tried organizing a few events along the lines of the Kalamela, but these did not take off because the art community did not feel a sense of ownership in a government event. One event which was conceptualized by K.T. Shivaprasad, one of the artists who participated in the Kala Yatre exhibition, and organized by Lalitakala Academy in 2002, came very close to the spirit of Kala Yatre. In this artist camp, which happened in a village called Kilara near Mandya, 10 artists from different parts of the state painted ten bullock carts. A local signboard and bullock cart painter also joined them. They stayed in a nearby town and painted under the shade of large trees. The whole village supported this endeavor, and each day a different family took care of their meals. For a long time, these painted bullock carts could be seen in these areas.

The Kalamelas also helped artists put their heads together and think of larger issues, and take stock of the art situation in the state and come up with demands and charters to put pressure on the government to act on various issues. By studying the charter of demands issued in 1983 (see Annexure 6), it is very clear that the government was still the major player in the 80s and 90s, holding the reins of agencies that could facilitate art production, sale, and consumption. Private galleries and collectors were very few. It was imperative that artists put pressure on the government to give them more grants, adequate representation in various committees, and avenues to earn their livelihood and visibility. By the late 1990s, as the IT industry became prominent and globalization swept in, the scenario changed. Numerous private galleries opened and many artists who were a part of the Kalamela started showing with those galleries. The art market boomed between the years 2004 and 2008. One can assume that the privatization of the gallery space and the neoliberal economy which pumped in money into the art world had some effect on the community spirit of the Kalamela. Hence, after 1993, there was a big gap before the next Kalamela edition in 2003, when it finally stopped. Many efforts to revive the Kalamela in the last couple of years have not seen fruition.

It is also possible that the changing practices of many young artists in Karnataka from the mid-1990s onward could not be accommodated in the template of the Kalamela. Even though the Kalamela did invite some prominent national-level artists as guests, it essentially had a Karnataka-centric imagination. Globalization mobilized artists in international circuits and Indian artists started studying, attending residencies, and showing in other countries. The seventh Khoj International Residency that happened in Venkatappa Art Gallery in 2003 revealed these shifting trends and signaled the end of the Kalamela initiative. Despite the closing of this chapter, however, it is important to offer due credit to the Kalamelas and the Kala Yatre for serving as landmark events that influenced the trajectory of modern and contemporary art in Karnataka.

Annexure 1

Artist groups that became part of the Kalamela in various editions:

1. Karnataka Painters

2. Rhythm Kala Samsthe, Bangalore

3. South Kanara Art Council, Udupi

4. Kuvempu Kala Samsthe

5. Samyojitha, Bangalore

6. Youth Writers and Artists Guild

7. Rainbow Arts Council, Dharwad

8. Dakahavisa, Davanagere

9. Karnataka Chitrakalavidara Mahaparishath, Bangalore

10. Chitrakala Shikshakara Sangha, Bangalore

11. Kalapragathi

Annexure 2

Details of different editions of the Kalamela:

KARNATAKA KALAMELA

These catalogues are available courtesy Marishamachar, Veeresh Rudraswamy and Ravikumar Kashi. Digitization of this material was undertaken by HSH.

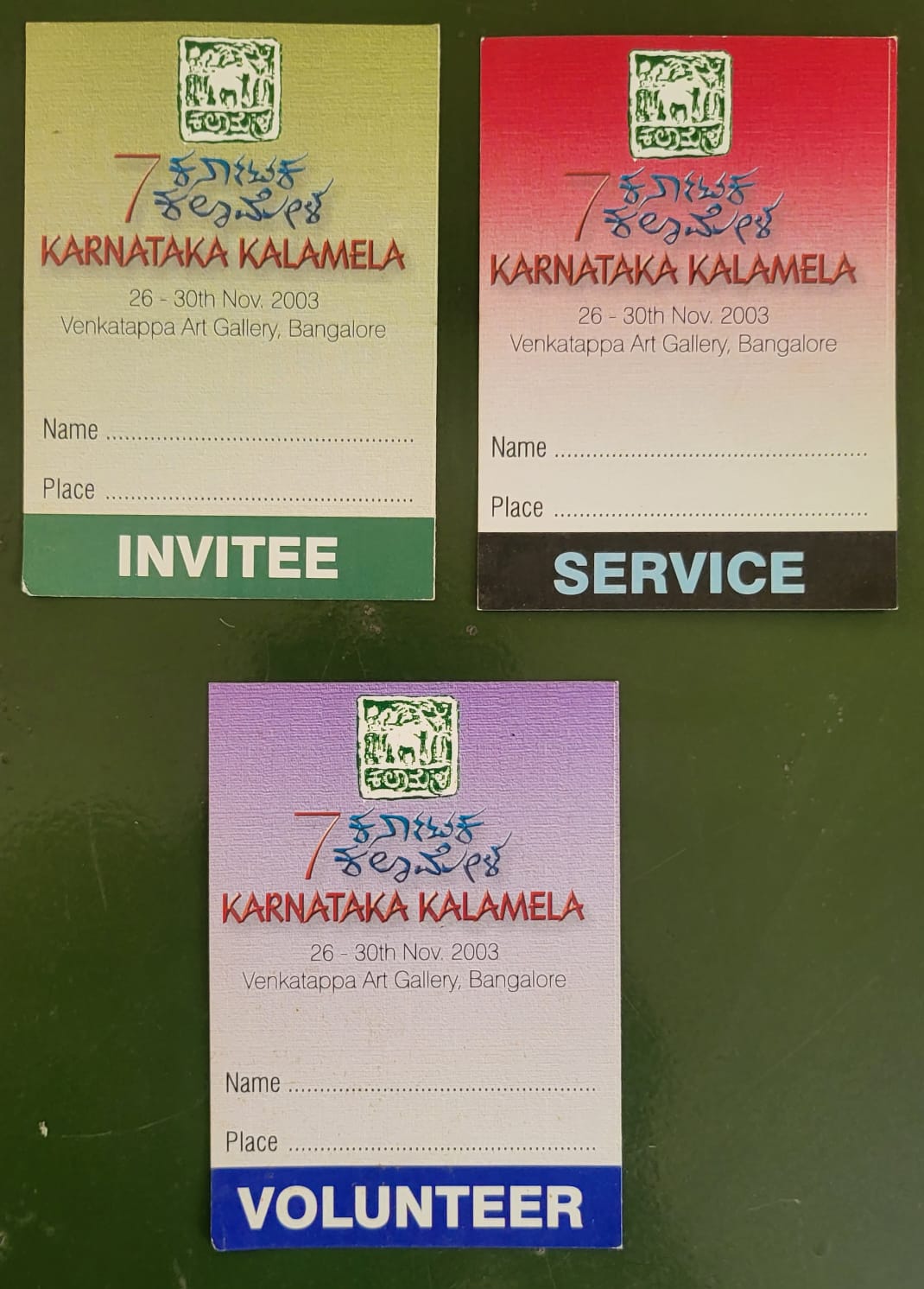

KARNATAKA KALAMELA 2003

In 2003, the last Kalamela after a hiatus did not publish a catalogue/souvenir. Instead, released a blank book with Kalamela branding on the cover. We release some of the images from this Kalamela and published materials courtesy Ravikumar Kashi, Krishna Setty and A M Prakash.

Annexure 4

KALA YATRE

This catalogue is available courtesy Marishamachar, Veeresh Rudraswamy and Ravikumar Kashi. Digitization of this material was undertaken by HSH.

![]()

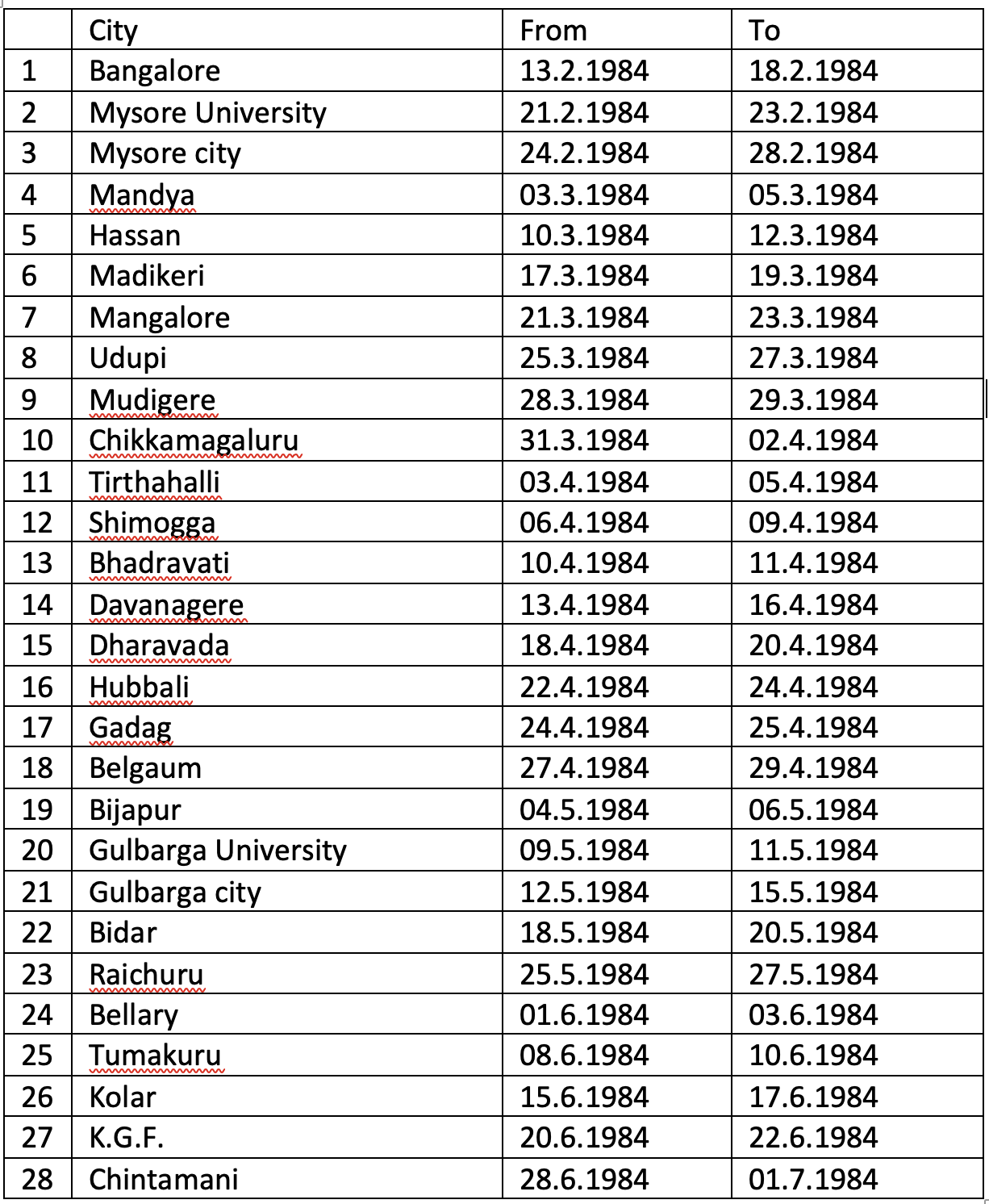

Cities where Kala Yatre exhibitions happened:

Annexure 5

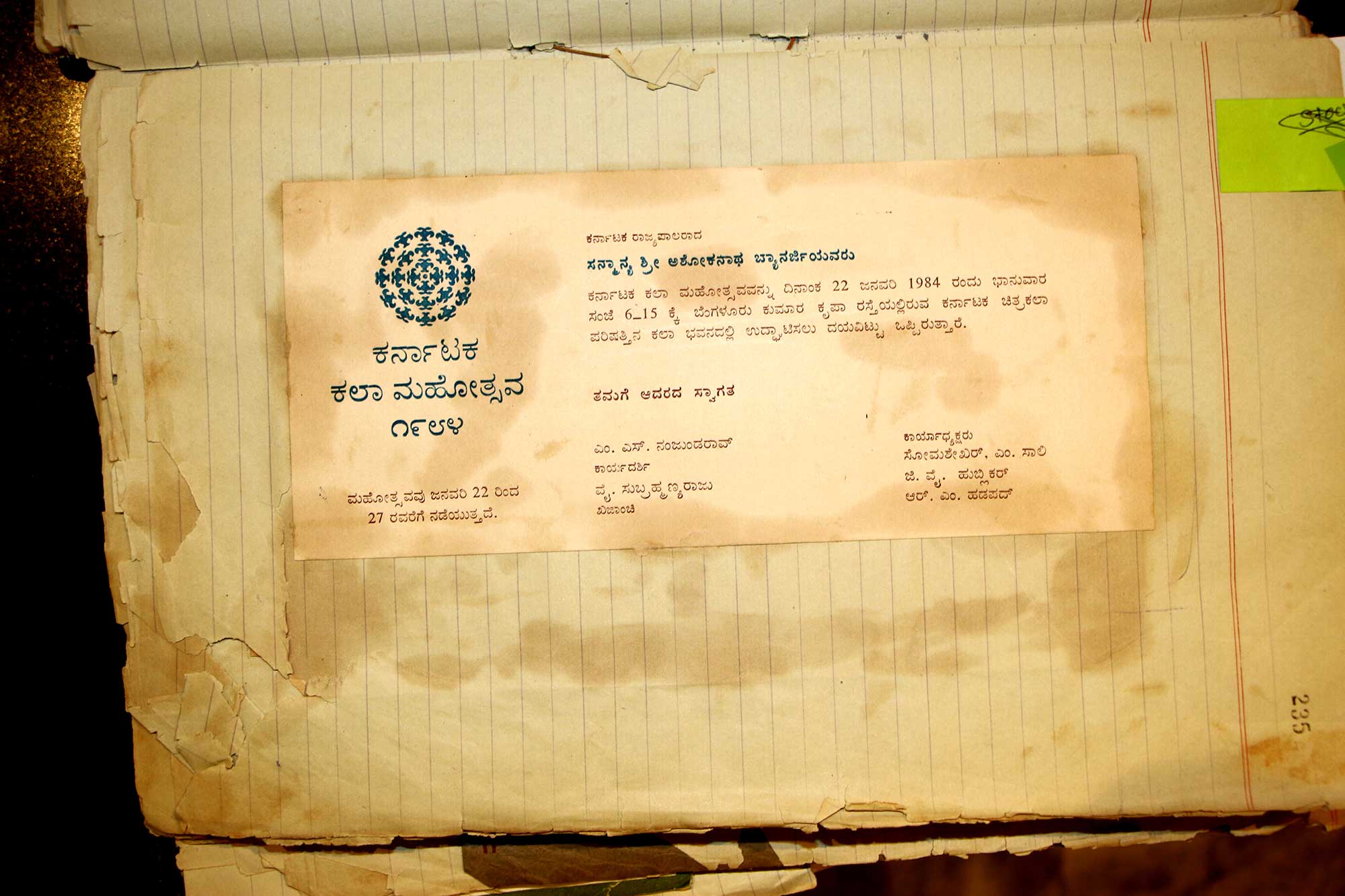

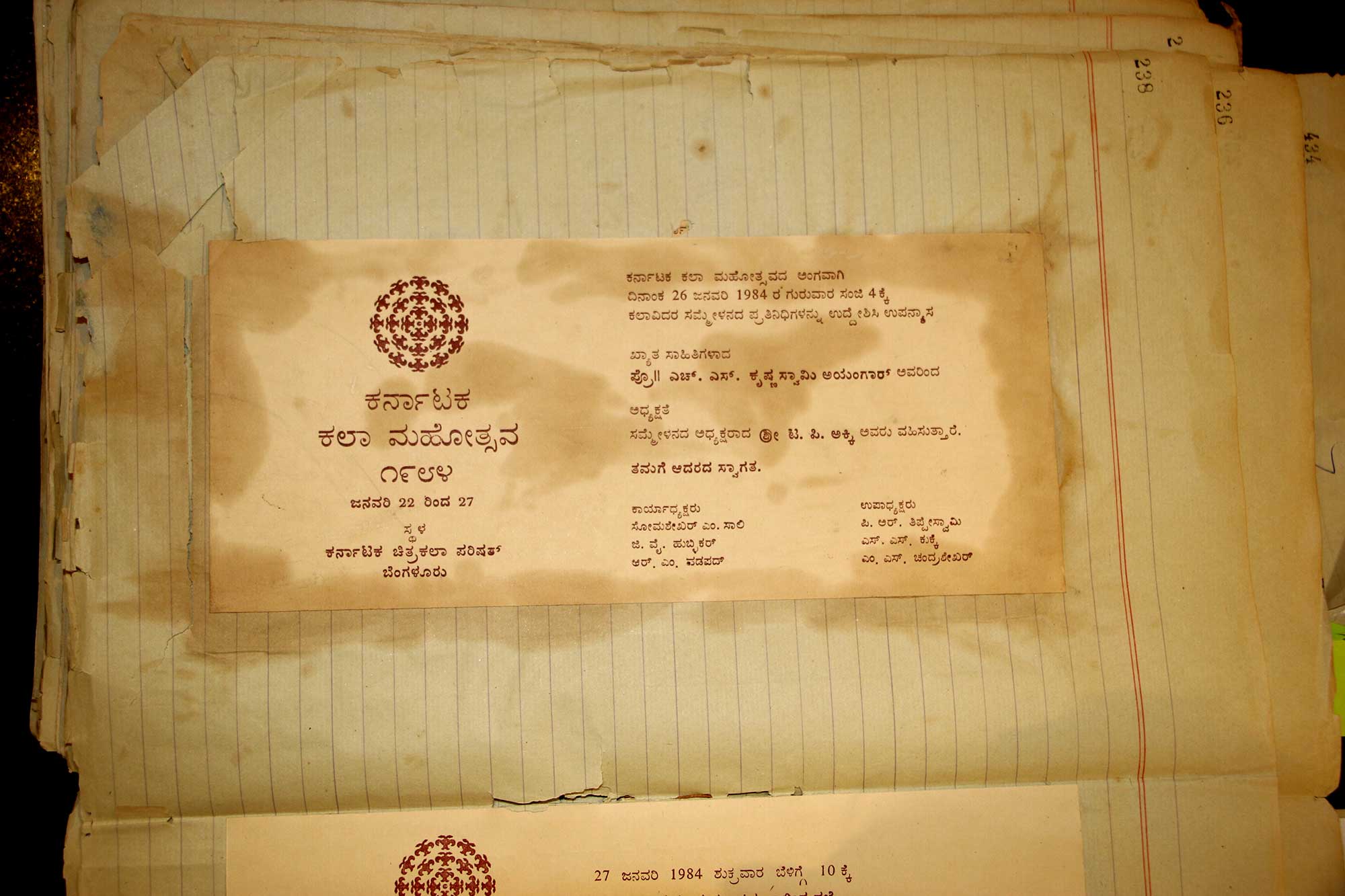

Kala Mahotsava Invites. Courtesy Karnataka Chitrakala Parishad archives

Kala Mahotsava: 22 to 27 January 1984 at Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath

Secretary: M.S. Nanjunda Rao

Vice Presidents: Somashekhar M. Sali, G.Y. Hublikar, R.M. Hadapad

Treasurer: Y. Subramanya Raju

Artist groups and art schools that participated in Kala Mahostava:

1.Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, Bangalore

2. Ken School of Arts, Bangalore

3. Vijaya Arts Institute, Gadaga

4. Ideal Fine Arts Institute, Gulbarga

5. Vijaya Mahantesh Lalitakala Vidyalaya, Hubballi

6. Sri Kalaniketana School of Arts, Mysore

7. Chitrakala Mandira School of Fine Arts, Katapadi, South Canara

8. Kalamandira, Bangalore

9. School of Arts, Dharwad

10. Benin Smith School of Arts, Belgaum

11. Yogita Kala Mandira, Bidar

12. J. S. Kala Shale, Betageri, Gadaga

13. Bharatiya Kalakendra, Dharwad

14. Youth Writers and Artists Guild, Bangalore

15. Chitra Mandira, Belgaum

16. Ravindra Kala Niketana, Tumkur

17. T. T. A. College, Dharwad

18. S. A. P. Staff Association

19. Sarkari Kala Shale, Davanagere

20. Sri Siddeshwara Kala Mandira, Bijapur

21. Karnataka Kalashalegala Sanyukta Sangha (Karnataka Art Schools United Front), Bangalore

22. Bengaluru Vibhagada Chitrakala Sangha, Bangalore

23. Vani School of Arts, Chikkanayakana Halli

Annexure 6

Charter of demands listed in the third Karnataka Kalamela in 1983:

1. Karnataka Kalamela urges the Government of Karnataka that while forming the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy committee, nominated members should be practicing/ professional artists, art experts, and critics only. Representation should also be given to groups which are active in the art field.

Proposed by: U. Bhaskar Rao

Seconded by: U. Ramesh Rao

2. Most of the art activities in the state are directed and funded by the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy. These activities are increasing day by day. Hence, we request the government to increase the annual grant given to the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy to 10 lakh rupees.

Proposed by: Khande Rao

Seconded by: Kaverappa

3. Kalamela urges the government to provide a separate building for the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy. This building should have facilities like galleries, space for display of works in the permanent collection of the academy, library, working studios for painting, sculpture, and printmaking to facilitate their creative work.

Proposed by: C. Chandrashekhar

Seconded by: Shivalingappa

4. Till the previously demanded building is ready, Kalamela urges the government to provide temporary art studio spaces for painting, sculpture, and printmaking behind Ravindra Kalakshetra.

Proposed by: V Madhu

Seconded by: K.V. Subramanyam

5. Kalamela urges the central government that vacant artists’ posts in Bangalore T.V. station have to be filled with eligible artists from Karnataka only.

Proposed by: G.K. Satya

Seconded by: J.M.S. Mani

6. Art coverage in media is abysmal in Karnataka. The Kalamela requests T.V., radio, and print media to cover art activities regularly and provide space for weekly review columns and partner in the development of art in the state.

Proposed by: C.S. Krishna Setty

Seconded by: H.N. Suresh

7. Kalamela strongly urges the government that while forming the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy not to nominate members from other academies. We also urge that those members who have completed two terms should not be re-nominated for a third term.

Proposed by: P.S. Kumar

Seconded by: Shankara Narayana

8. This conference urges the government to appoint eligible artists only from Karnataka to fill the posts in art colleges and other educational institutions.

Proposed by: S. Shamsunder

Seconded by: Sheela Gowda

9. Kalamela urges the government to appoint artists as officers to beautify government offices and public spaces and to increase awareness among the public.

Proposed by: N. Marishamachar

Seconded by: C. Chandrashekhar

10. Kalamela urges the government to air-condition the Venkatappa Art Gallery immediately and provide lift facilities.

Proposed by: G.K. Satya

Seconded by: Venkatachalapathi

11. Kalamela urges the government to keep aside 2% of the budget spent on traveler’s bungalows, factories, and buildings to acquire art. New buildings should also have murals. All these orders have to be channeled through the Karnataka Lalitakala Academy.

Proposed by: Khande Rao

Seconded by: S. Sulochana

12.Kalamela urges the government to take necessary steps to install permanent public sculptures created by creative artists of Karnataka, on the lines of Delhi and Chandigarh, in circles, parks, and street corners to beautify the city and to improve people’s awareness of art.

Proposed by: U. Bhaskar Rao

Seconded by: Gurugangaiaha

13.To enable artists to stay together and continue their interaction and art practice we urge the government to create artists colonies in Bangalore and other major cities of the state.

Proposed by: Rumale C.

Seconded by: Kaverappa

14.Artists are working in different towns and cities in rented places used as studios. We urge the government to reserve 5% sites in new areas being developed for artists. We also urge the government to develop artist studios on the lines of the studios in Kalanagar, Mumbai.

Proposed by: T. Shobha

Seconded by: V.R.C. Shekhar

15.We urge the government that when committees are formed to purchase art for the government it should comprise as many artists as possible.

Proposed by: J.M.S. Mani

Seconded by: V.R.C. Shekhar

16.In the past, the Government Museum was purchasing art for its collection, which has stopped now. We urge the concerned authorities to restart this acquisition process.

Proposed by: S. Shamsunder

Seconded by: Kulakarni

Ravikumar Kashi is a Bangalore based artist, educator, art writer and researcher. Over the years, he has developed an unconventional artistic vocabulary, supported by a personalised logic, and an aesthetic structure born from a process-based act of combining ideas.