Tracing Fifty Years of Jadavpur University Photographic Club [1967–2017]

Sourav Sil

Published on 10.5.2023

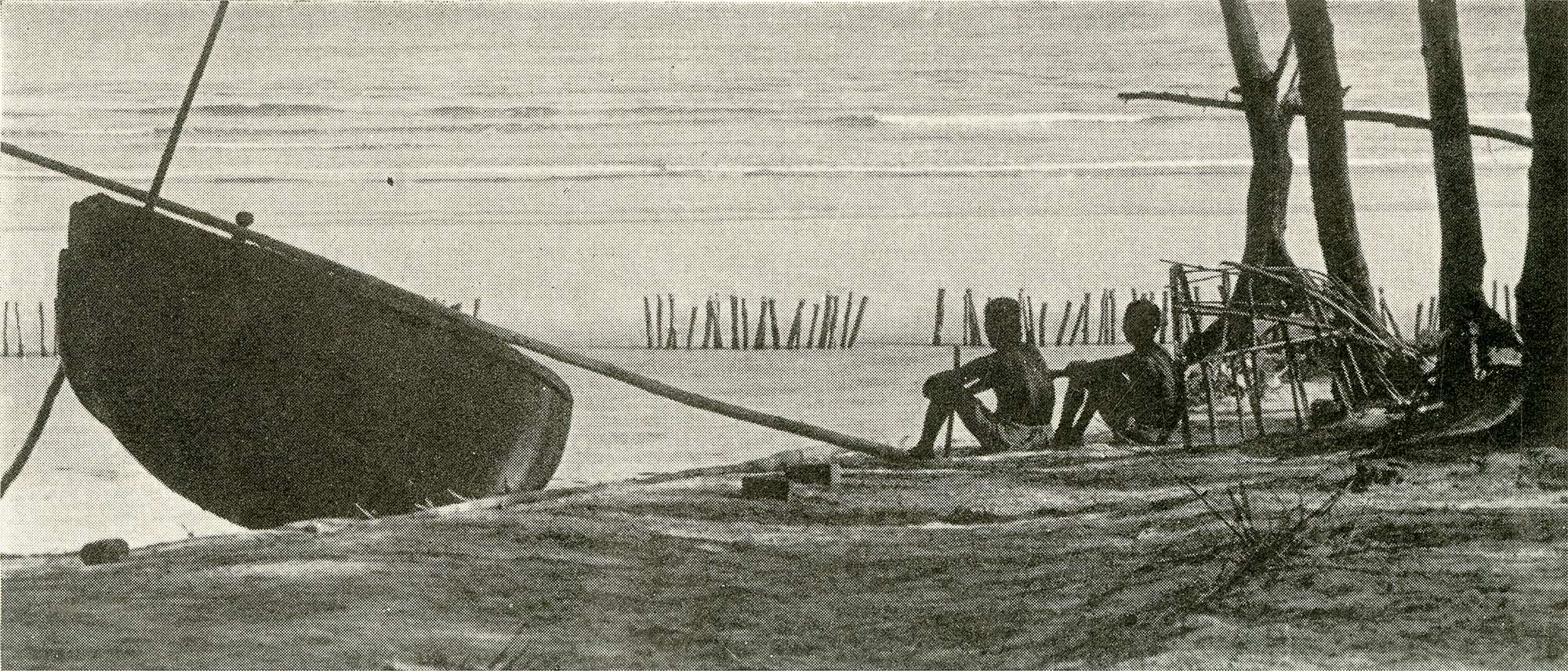

Amit Kanjilal, Rest, 1971. Halftone print. Scanned from the souvenir of Fifth Annual Exhibition with Third All India Students’ Section, June 1971, held at the Club Gallery. Courtesy: JUPC.

Biplob Sardar, United Effort, c. 2000. Gelatin silver print, 38 x 18 cm. Courtesy: JUPC.

The Calcutta of 1967 was a tempestuous one. Following the police

excesses during the Food Movement,[1] West Bengal’s first

non-Congress government had come to power through a post-poll coalition between

the Bangla Congress, a breakaway faction of the Congress party, and the

Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) and its allies. A day after the new

government was sworn in, the far-left sections of the CPI(M), inspired by the political

ideology of Mao Tse-tung, began an armed struggle of peasants in rural north

Bengal against the oppression of the wealthy landowning classes. The Naxalbari

uprising, as the movement came to be known, spread like wildfire and soon

captured the revolutionary zeitgeist of the academic centers of the state’s

capital. The verdant campus of Jadavpur University (JU), skirting Calcutta’s

southern fringes, became then one of the many theaters of Bengal’s political

upheavals and social churning. Nestled within these coordinates marked by

rebellious dreams and quotidian bedlam, and yet untied to it, the university’s

photographic club had hosted its first photographic exhibition. Jadavpur

University Photographic Club (JUPC), as the club is called till date, was just

three years old then.

Souvik Kumar Basu, Children at play, c. 1998. Gelatin silver print, 38.4 x 28.9 cm. Courtesy: JUPC

Over the next few years, the event of the

exhibition, that furtively assumed the shape of a ritual, kindled within the

club the building of a new world—of an idiosyncratic social space which stretched

itself out far beyond the university walls, establishing affiliations to a

flourishing network of amateur photographic clubs strewn across the city. From

‘salon’ to ‘contest’ to ‘festival’, the anatomy of the JUPC exhibition has undergone

numerous metamorphoses over five decades of its iterations, but its kinship

with the club’s shared registers of image-making has not suffered a bruise. As

an active member of JUPC during the years 2012-16, I keenly observed, took part

in, and later helped organize and steer a few editions of this enterprise. This

intimate engagement allowed me to discern how critical this apparatus of

producing exhibitions is to the space that JUPC has appropriated for itself within

its university’s ecology. In this essay, using my own subjectivity as an

erstwhile member, and through a brief archival exploration, I attempt to trace

the outlines of this appropriated space through the locus of JUPC’s

self-stirred artistic practice between 1967 and 2017.

Abhishek

Mitra, Untitled, c. 2001. Chromogenic print, 40 x 26.9 cm. Courtesy: JUPC.

The club is said to have been born when one fine

day in 1964, Prof. Robin Wood, a Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) faculty from

Cambridge University teaching at JU, had gathered a bunch of zealous students

and teachers to turn one of the washrooms at the Geological Sciences department

into a photographic darkroom. The

fledgling initiative, with its largely apolitical ambition, was quick to

receive the patronage of the university administration who were hard-pressed to

dispel the perception of this state-owned institution as anarchic, recalcitrant,

and anti-government owing to the regular student protests. With its positive

image of a productive venture, JUPC soon matured into an official activity center

with its own exhibition hall, darkrooms, studio, and even a constitution. When

we think about alternative or independent art spaces, we commonly tend to

imagine sites that are manifestly aware of its otherness—sites that are

engendered by reactions against the stultifying conformity to the so-called mainstream.

JUPC did not possess any such awareness or origin chronicle. It evolved in a

matrix whose aesthetic tenets stemmed from the fin de siècle Pictorialist

movement. In American and European photography, these tenets were pushed to the

margins by the headway of successive styles, movements, and ideas, but when we

shift our vantage point to India, we find that for much of its photographic

history, Pictorialism has been the most popular vocabulary among all ‘serious

amateur’ photographers.

In an article published in The Englishman on

2 May 1856, one of the earliest photographic clubs in Calcutta, the

Photographic Society of Bengal, is quoted as expressing an urgent need to

establish ‘a school of practical photography’ as part of the society’s primary

objectives. In the following decades, the city witnessed the founding of

countless institutions (many of whom were quite short-lived yet influential)

that strived to actuate pedagogic modules on photographic practice[2].

A century later, by the end of the 1960s, photography had become an integral part

of the curriculum in most of the Government Colleges of Art in India

established during the colonial period, as well as in the art colleges at

Santiniketan and Baroda. Yet it was far from enjoying the status that was

accorded to the disciplines of painting and sculpture. Neither the Lalit Kala

Akademi nor the National Gallery of Modern Art had any program for collecting

or displaying photography[3].

In 1968, seven artists teaching at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao

University (MSU) in Baroda—Jyoti Bhatt, Feroz Katpitia, Narendra Mehta, Jeram

Patel, Vinodray Patel, Vinod S. Patel, and Gulammohammed Sheikh exhibited their

experimental photographic works at Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay with an

intent to claim recognition for photography as fine art. The exhibition was

named, satirically or otherwise, Painters with a Camera.

Saktipriya Bhattacharyya, Composition No. 1, 1971. Halftone print. Scanned from the souvenir of the Fifth Annual Exhibition 1971. Courtesy: JUPC.

One of the medals awarded to the winners of the XXII All India Salon of Photography. Courtesy: JUPC.

A long way off from these zones of mainstream art

economies, presumably oblivious of such discourses, different groups of amateur

photographers aspired for similar recognition. The establishment of the

Federation of Indian Photography (FIP) in 1952—modeled on the Photographic

Society of America (PSA), the Fédération Internationale de l’Art Photographique

(FIAP), and the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) of London—encouraged these

groups to constitute a host of photographic societies across the major urban

centers in India. Among the ones that came up in Calcutta, the Photographic

Association of Bengal (PAB) and the Photographic Association of Dumdum (PAD)

emerged as the most pivotal in Bengal’s pictorialist circuit. Their membership

was largely comprised of middle-class working professionals, predominantly men,

from the genteel or bhadralok society, who irrespective of their

political beliefs, passionately supported the cause of elevating photography to

the echelons of fine art. As JUPC emerged on the scene and began looking to

these bodies for mentorship, the imagination shaping its space was struck by

the same pursuit. The connection was woven over many short lectures, workshops,

and practical training sessions in which senior members of PAB and PAD were

invited as tutors. A more vigorous exchange took place when such members acted

as judges in the contests organized by the club. While the members listened to

the judges’ observations as they dissected each print and slide in terms of its

mood, composition, tonality, and quality of reproduction, it chiseled their

ways of seeing the world. The process culminated in the yearly exhibitions, where

the selected photographs were displayed and the winners awarded, and the event

thus became a meeting ground of like-minded ‘serious amateur’ photographers who

shared with each other their admiration, anxieties, and deprecations alike.

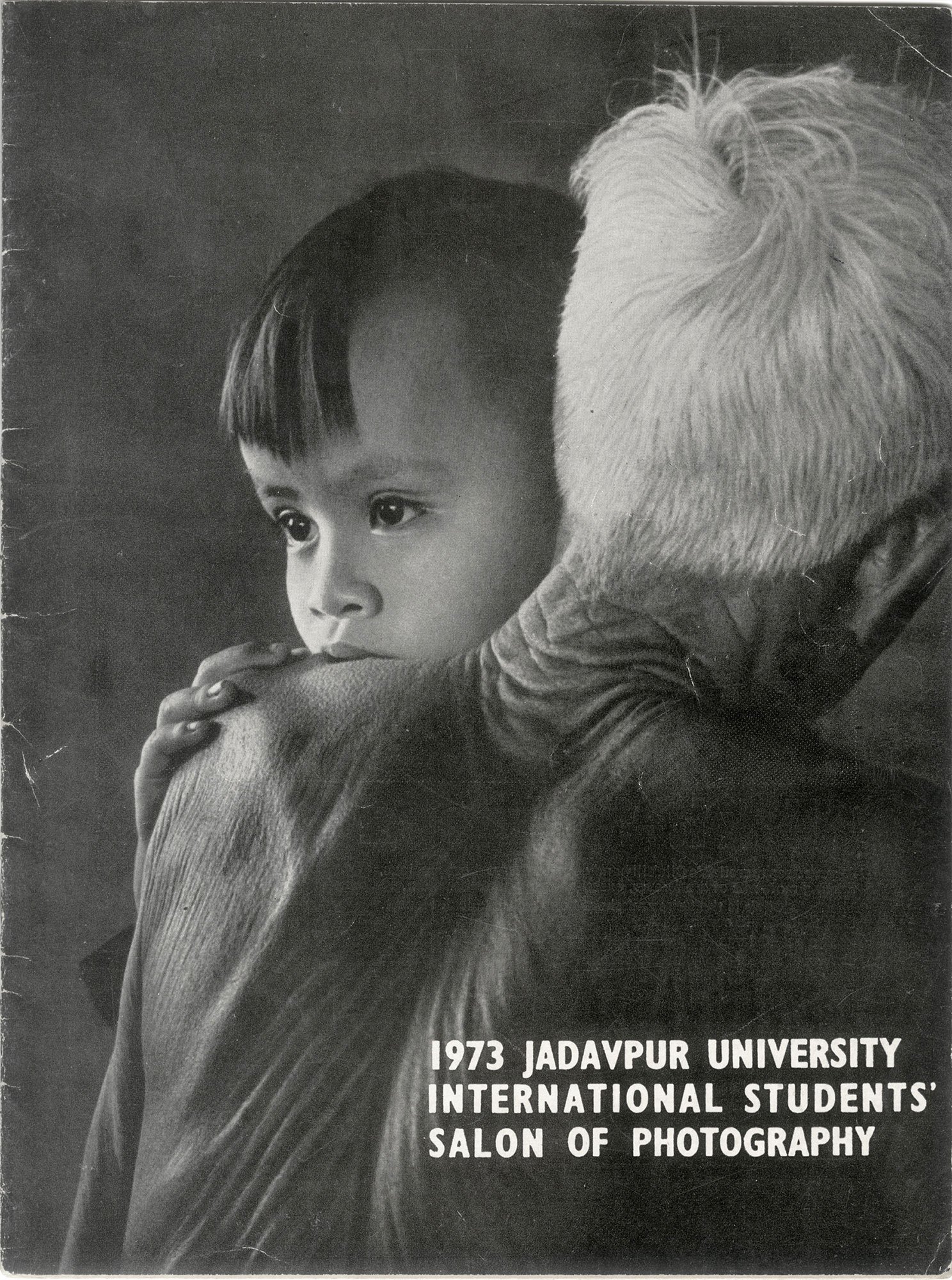

Cover of the souvenir

of the first international salon organized by JUPC, 1973. The cover photograph,

Grandfather, is by Nguyen Thanh Hai from Vietnam. Courtesy: JUPC.

As JUPC became part of an expansive nation-wide

network that sought to embrace the romanticism, symbolism, and heightened

idealism of pictorialist photography, it started organizing an All-India

Students’ Salon segment along with its members’ section as part of the

contests. In March 1970, at its fourth annual exhibition and second edition of

All-India Students’ Salon, JUPC saw an overwhelming participation from

institutes across the country, including Bangalore University, Film Institute

of India (Pune), Benaras Hindu University, and MSU (Baroda). At the end of the

year, at a time when the Naxalite movement in Bengal reached its denouement,

the JU Vice-Chancellor Gopal Chandra Sen was murdered in broad daylight a few

yards away from the club premises. During one of the interviews that I

conducted with erstwhile members, I had asked Saktipriya Bhattacharyya, an ardent

participant in the photographic club during the early 1970s, the reason why no

one in JUPC kept any document of such tumultuous times. In response, he

explained to me how the sociopolitical turmoil was never a part of their

photographic preoccupation. He even added that the members were so trammeled by

the need to master technical processes that they could not spare time for

anything more exacting. Bhattacharya himself was adept at experimenting with

darkroom techniques: he would superimpose multiple negatives to create

photomontages or transfer negatives onto lith film to generate high contrast

enlargements. However, as I browsed through the salon souvenirs (JUPC uses the

term ‘souvenir’ to refer to its exhibition catalogs), I found that traces of such

experiments were few and far between.

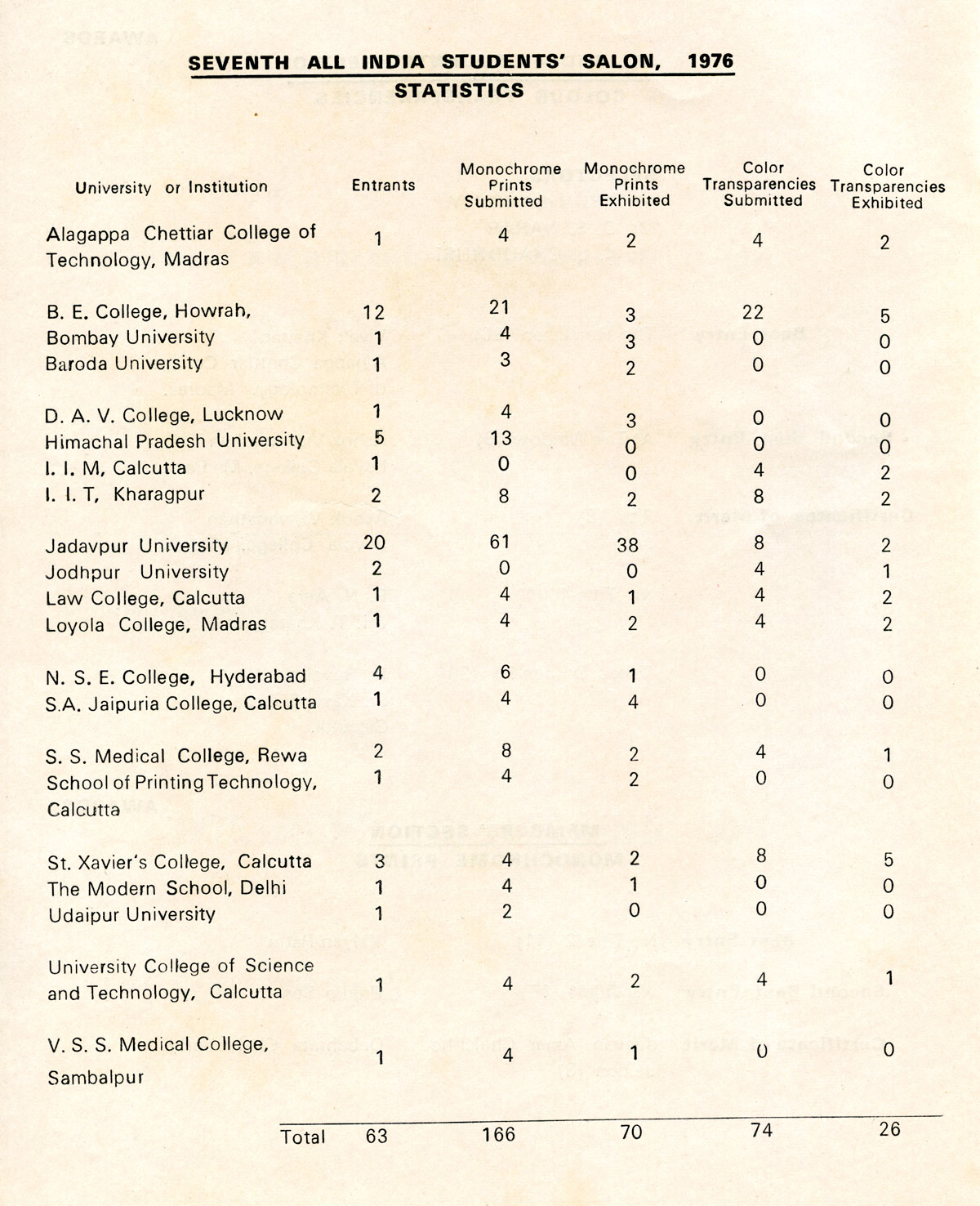

Participation statistics of the seventh All India Students’ Salon, 1976. Courtesy: JUPC

The entry form

of the Twelfth All India Salon of Photography, 1983. Courtesy: JUPC.

Advertisement for AGFA Click- III Camera. Scanned from the souvenir of the fourth annual exhibition, June 1971. Courtesy: JUPC

In 1973, when the world was being torn apart by the

Cold War, the club organized its first International Students’ Salon of

Photography which received entries from 21 countries across both the

ideological Blocs. The cover photograph of the souvenir, probably by design,

was chosen from Vietnam, although the image—of a wide-eyed boy hugging his

grandfather whose softly-lit wrinkled back faces the camera as the guileless

somber gaze of the child pierces out of the frame—was far removed from the immediacy

of the contemporary moment. The program was supported by Agfa-Gevaert India

Limited[4] as well as the university’s Alumni Association. A special award was instituted

in the memory of Prof. Gopal Chandra Sen[5].

This model of raising funds through a combination of corporate sponsorship and

alumni donations enabled a transition in the location of the future exhibitions

from the freely available space within the campus to the more exquisite gallery

halls of the Academy of Fine Arts or Birla Academy of Art and Culture[6]—places

which were usually reserved for painting and sculpture displays. The later

salons also received endorsements in the form of recognition by bodies like the

FIP and the India International Photographic Council (IIPC). IIPC, founded by

the famous Delhi-based pictorialist O.P. Sharma, awarded a separate prize to

the best entrant in the JUPC salons. However, these associations often came at

the cost of promulgating formulaic approaches among both entrants and judges of

the contests.

“Selection of the same type of subject and a very

typical approach to composition mark the pattern of any salon”—“The motive of

our photographer seems to be reduced to standards of passing the scrutiny of

the judges alone”—“There is perhaps a question–where is the new direction? The

salon looks back with an irresponsive air. The new direction is yet to be found

out.”[7]Throughout the 1980s, as these foreword texts of the salon souvenirs suggest,

there was an incessant critical re-evaluation of this ossified aesthetic regime

within the club.

Navigating through the fragments of what remains in

the archives, it is difficult to map the direct impact of such assessments on

the club’s practice but returning to the cue in Bhattacharyya’s answer, it is

germane to consider JUPC’s space from the point of view of its peculiar

limitations. As students of a premier educational institute, JUPC members have

always had to pursue their recreation alongside tackling a prodigious burden of

academic pressure, while having little or no access to funds and resources of

their own. The university grants have always been exiguous: the club’s annual

reports reveal the grant sum as Rs. 7796 in 1978-79, Rs. 4500 in 1980-82, and

Rs. 19293 in 2005-06. Evidently, the amounts were inadequate to support the

club’s infrastructure as well as the activities of every member. In such a

situation, the club had to devise its own financial model to maintain a

considerable degree of self-sufficiency. It had instituted a separate

department called the ‘job section’ which provided professional services like

developing, printing, enlarging, slide-making, and event documentation to the

university community. The largest share of the club’s revenue even today comes

from documenting the annual convocation ceremony. Every year, JUPC members are

given sole access to the convocation dais, where they take photographs of

hundreds of graduating students at the inimitable moment of them receiving

their degrees and medals. The management of the event proves to be a gargantuan

task and requires several weeks of rehearsals, but the club’s economic

dependence on this single event also hinges on a tremendous degree of precarity.

If its actions are perceived as anti-authority, the delicate balance on which

its hard-earned freedom hangs would capsize. This arrangement alienates the

club from its environs whenever the student community protests against the

administration. But the fact that JUPC works as a commune, raises money to buy

its own equipment through shared labor, distributes the resources equally among

its members, and travels together for photographic expeditions, fosters a

unique sociality that is key to the production of its space.

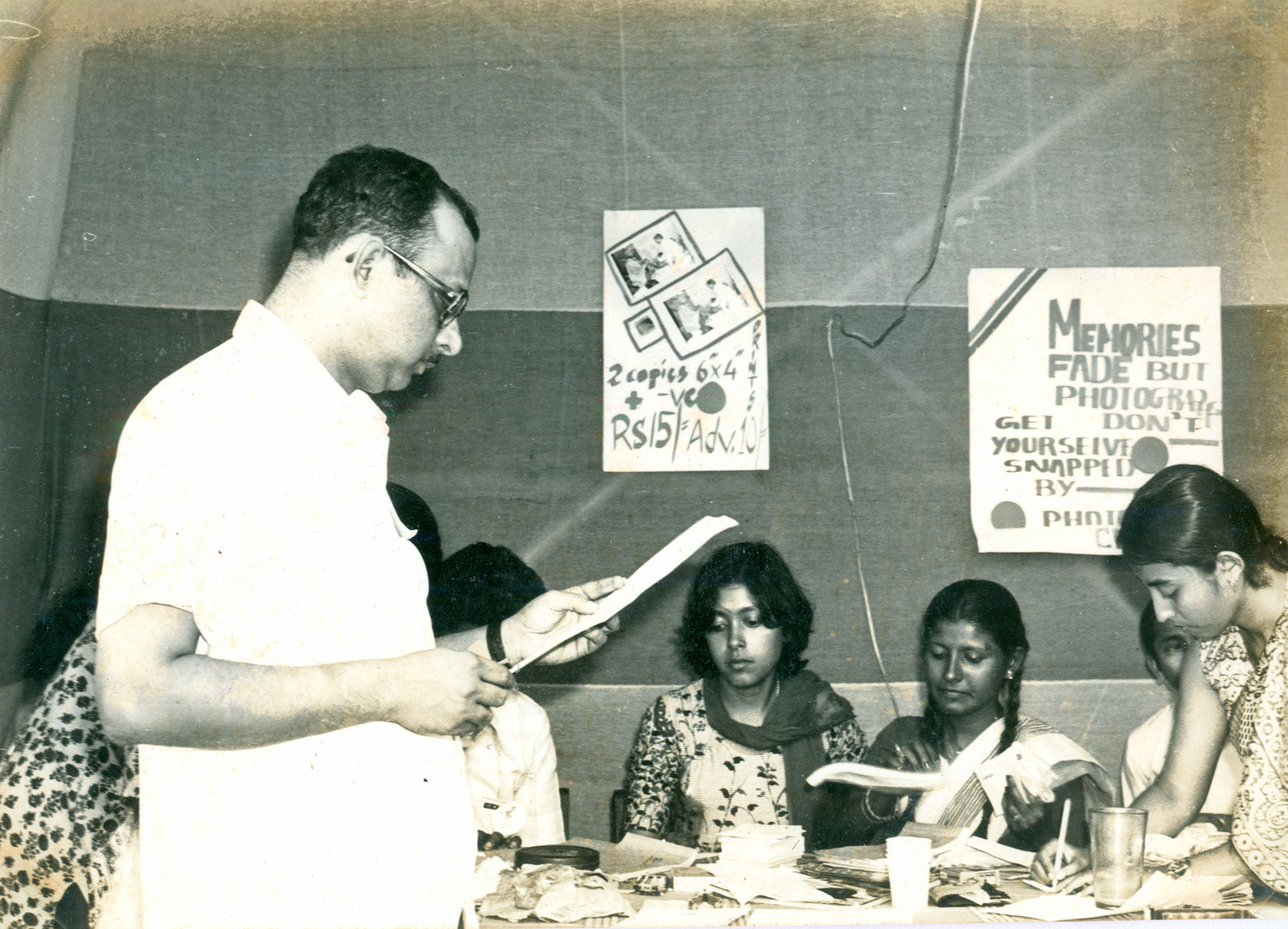

Ashoke Mukhopadhyay, one of the founding members of JUPC, at the convocation service cash counter along with other student members. Gelatin silver print, 19.8 x 14 cm. Courtesy: JUPC.

In the JUPC annual report of 1978-79, the club

secretary underscores the inconvenience of running the job section with

personal cameras of the members and makes a plea for buying a camera and a

flash gun. The first camera of the club, a Yashica 635 twin lens reflex (TLR),

was bought with funds raised by Prof. Wood around the end of the 1960s, but

most students in the early decades had to purchase their own cameras or borrow

from fellow members. The club had a dedicated ‘paper and film’ section. In the

1980s, it used to maintain a stock of NP 55 and NP 7 manufactured by ORWO and

Brovira photographic papers manufactured by Agfa-Gevaert. The films were often

procured from the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) and were made

available to every member through fixed allocations based on supply and

availability at subsidized rates. An official part-time position of ‘darkroom assistant’

was also set up. Badal C. Datta, who was put in charge of the position at the

time, immensely contributed to the commune’s fecundity. From the early 2000s,

as film, paper, and chemicals started getting harder to procure, the members

started raising a demand before the university authority to allow a special

grant that would enable the club to shift to a digital setup. The club

eventually purchased its first computer in 2006—the year in which it also got

its website. In the subsequent year, a digital scanner was bought along with

two single lens reflex (SLR) cameras. In 2008, the members contributed their

earnings from the photographic assignments (the term ‘job section’ had fallen

out of use by then) toward buying a new digital equipment set: a Nikon D40 with

18-55 mm kit lens, three Canon EOS 400D with 18-55 mm kit lenses, one Canon

75-300 mm telephoto lens, and another computer system. In 2009-10, the

university finally agreed to the club’s demands and offered a lumpsum grant to

the tune of Rs. 57000. A Nikon D3000 was bought along with lens filters,

tripods, and flash lights. By the end of the decade, the enlargers, film-drying

cabinets, slide projectors, and darkroom registers started gathering dust while

pirated versions of Photoshop and Lightroom were surreptitiously consummating

the transformation.

A club member pointing at the collection of SLR cameras in the club’s repository. The colour enlarger, which now lies as an unidentifiable pile of junk, can be spotted in all its former glory in the background, c. 2000. The photograph was perhaps taken during one of the convocations as the member can be seen wearing a badge clipped to his shirt pocket. Such badges are issued to every member who participates in the convocation photographic service for easy identification amidst the brimming crowd. Courtesy: JUPC.

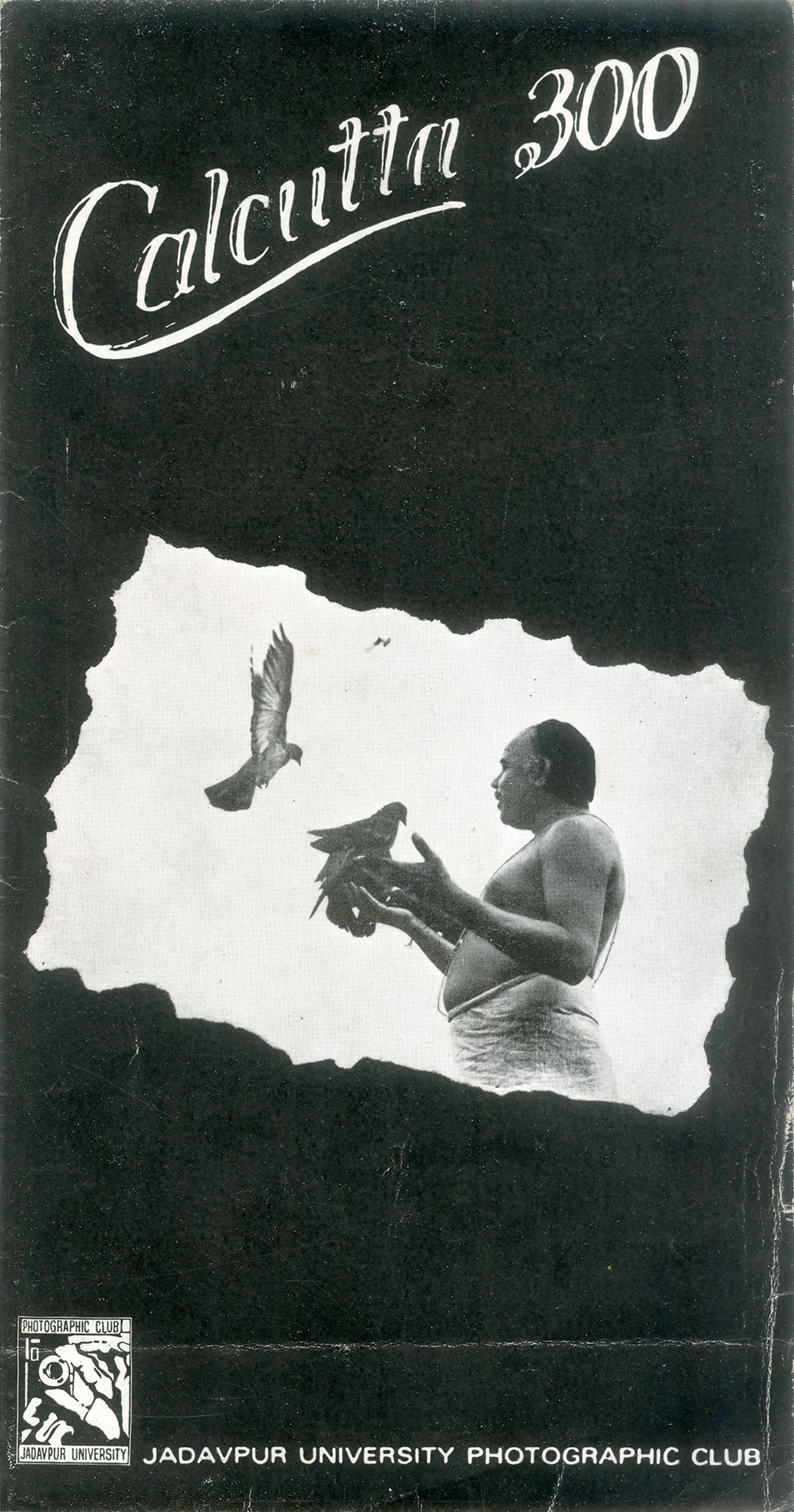

Cover of the special intra-club salon called Calcutta 300 organised in 1990. The cover photograph is taken by Bhaskar Basu. Courtesy: JUPC.

Tumpa Mondal, image from the series Future Professionals, Kolkata, c. 2006. Digital scan. Courtesy: Tumpa Mondal.

Swarat Dey, Face Puzzle, c. 2015. Courtesy: Swarat Dey.

These adaptations to changes in media and

technology were accompanied by the changes in the landscape of JUPC’s

exhibitions. In 1990, JUPC broke away from the ennui of salons for the first

time and organized its first theme-based photography exhibition called

“Calcutta 300” on the occasion of the tercentenary celebration of Calcutta’s

founding[8],

where unlike the usual salon categories of ‘pictorial’ or ‘nature’ the

photographs were grouped under ‘Struggles’, ‘Calcuttans’, ‘Calcutta, My Dream’,

and ‘Festive Calcutta’. Within another decade, the salon format was replaced by

theme-based contests. A few members, who were working in the field of

advertising photography, introduced the idea of a photographic series or what

they called ‘portfolio’ to the club. The 2005 members’ exhibition titled

“Barnodrik” presented a separate feature section for photo-stories by select

members. In the following year, a national contest of photo-stories was

organized where Tumpa Mondal, a JUPC member, won the second prize for her

remarkable series on the life inside a women’s hostel. From 2008, this contest

was christened “Montage”—a name that survives till date. In the next few years,

the club was reeling under the burden of the shift from analog to digital as

well as burgeoning expenses. It became imperative to ensure a large number of

entries in the contest so that the sum raised through the entry fees was sufficient.

Hence the category of ‘photo-story’ was dropped as there were not enough

entrants and the contest reverted to single images. The digital photo-editing

tools also brought in a lot of anxiety related to the purity and truth of

images. Staging and manipulation of any sort came to be considered as unethical,

and yet landscapes with superimposed clouds or street scenes with removed

figures frequently made it to the exhibitions on the sly. By the time I joined

JUPC in 2012, the attitudes did not suffer much change, but the sources of

influence started relocating to streams of social media groups and photography

blogs. The history of photography came filtered and certain strains of practice

that can be euphemistically called ‘street photography’ became the order of the

day.

Indranil Banerjee, Untitled, c. 2015. Courtesy: Indranil Banerjee.

In the last year of my university, in 2016, we came

up with the idea of an Indo-Bangladesh contest to radically increase the

participation figures when we had found a thriving network of student-run

photographic clubs in our neighboring country. It was a desperate attempt to

augment the club’s income from the contest entry fees while marginally reducing

its reliance on the convocation revenues. The event came to fruition with the support

of the photographic clubs of Bangladesh University of Engineering and

Technology, Jahangirnagar University, and Islamic University of Technology. The

final exhibition, that was held at the Indian Council for Cultural Relations

(ICCR), was complemented by a show of photobooks which were loaned to JUPC by a

few senior photographers. The exposure to Sally Mann’s Immediate Family,

Roger Ballen’s Asylum of the Birds, Robert Frank’s The Americans,

Josef Koudelka’s Gypsies, and multiple works of Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin,

Dayanita Singh, and Prabuddha Dasgupta unlocked for the club the gateway to a

universe that was until that moment completely unfamiliar. On the last day of

the exhibition, photographer Prashant Panjiar had paid a brief visit to the ICCR

gallery. The club members were undoubtedly elated. Panjiar, who was one of the

curators of the Delhi Photo Festival (now discontinued), was highly impressed

with the efforts of JUPC and urged the members to think bigger for the next

year. Such a stimulus led JUPC to come up with the Jadavpur University Photo

Fest (JUPF) in 2017. Its stated intent was to “understand the role of

photography within the realm of contemporary art as well as promote alternate

discourses”. An active involvement of Vice-Chancellor Suranjan Das ensured that

the festival was supported by Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata and

Victoria Memorial Hall (VMH), Kolkata. Jayanta Sengupta, curator of the VMH and

Das’ long-time friend, was also instrumental in structuring the festival. The

highlights of the program included a keynote lecture by curator Rahaab Allana,

workshops by photographers Sarker Protick and Altaf Qadri, and open-air

exhibitions spread across the VMH grounds as well as the university campus,

curated by Harsha Vadlamani.

Boris Eldagsen, one of the artists exhibited at the Jadavpur University Photo Fest 2017, photographing the installation of his work at the university’s open-air theatre. Courtesy: Arijit Pramanick.

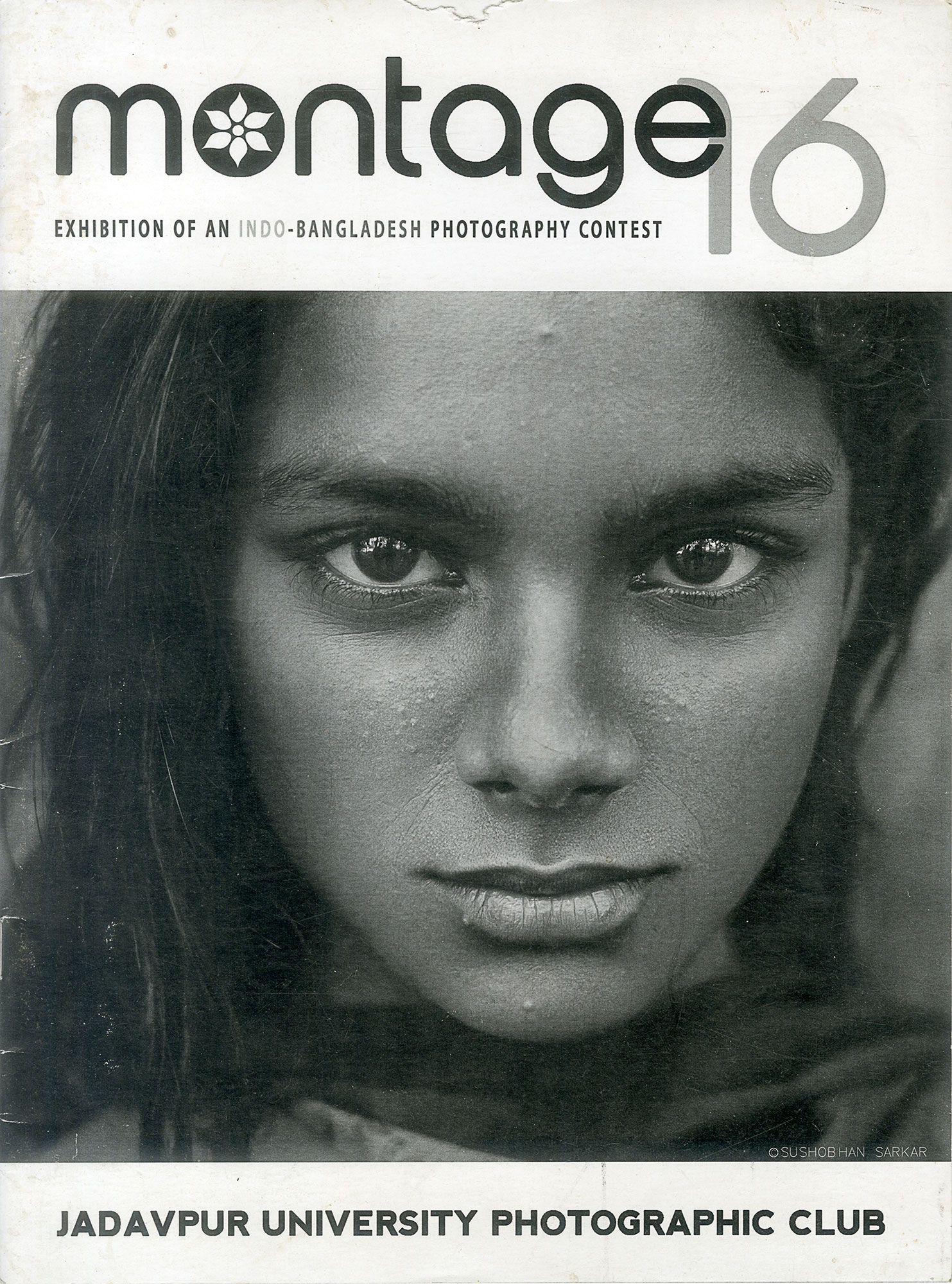

Cover of the souvenir for the annual contest exhibition, 2016. The cover photograph titled Rebeccais by Sushobhan Sarker. It was awarded the Certificate of Merit in the open (non-thematic) category. Courtesy: JUPC.

Sarker Protick, a photographer and a faculty member of Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka, offering an artist talk at Gandhi Bhavan, Jadavpur University during the festival, 2017. Courtesy: Sourajit Sah

This five-decade-long trajectory of JUPC is also,

in a way, a chronicle of the ‘serious amateur’ figure. Within the subjectivity

of the ‘serious amateur’, the space of JUPC was never a parallel world. It was

rather part of the most dominant and visible strain of photography. Even

well-known photojournalists like S Paul were more disposed toward this strain:

it is said that once, instead of photographing the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

cutting a ribbon at a ceremony, he chose to capture a line of swans flying

overhead[9].

Therefore, it is not surprising that many JUPC members preferred to regard Paul

as their guru over his more famous brother and mentee, Raghu Rai. The ‘amateur’

figure has consistently been defined by their claim for recognizing photography

as art, but it is ironical that when, at the turn of the present century,

photography starts acquiring space within the Indian contemporary art market,

the ‘amateur’ figure slowly becomes evanescent. With the growth of digital technology

and rising penetration of the internet, ‘serious’ photographers can now

practice as well as educate themselves without accessing the photo-club network

and its infrastructure. They no longer need to seek validation of their work

from the photo-club mentors and their salons. Instead, they can look up to

photographers who do not necessarily hail from art schools but are being acknowledged

and feted today by galleries, foundations, and collectives sprouting up from

the mainstream art world economy. It is within this broader context that JUPC’s

photographic space appears as marginal. However, JUPC is also unique in the way

it bears simultaneously the old and the new: each year it is populated by a

fresh batch of students as an old one bids adieu. This periodic rejigging has

encouraged the transitions in the practice and structure of its exhibitions over

the years, but the precipitous upscaling of the 2017 event to a photo-festival

left the ground tremulous. The club became doubtful of its usual approaches and

methods and yet the commitment toward more refined, informed, and slow

photography was too demanding for students just looking for an engaging hobby.

In the following years, a few members began experimenting with form and

material in their practice, but it is yet to be seen whether JUPC’s collective space

can accommodate a veritable new path independent of the dogmas of its past.

[1] Following the Partition of India and the resulting influx of more than two million refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), West Bengal suffered an acute scarcity of food grains owing to a malfunctioning public distribution system (PDS). The faulty policies of successive Congress governments in the state led to hoarding and black-marketeering, creating an almost famine-like situation. This led to the first Food Movement in 1959. Although the movement was withdrawn formally in September 1959, its spirit was alive, which reignited in 1966 after the police opened fire on a crowd demonstrating against scarcity of kerosene and rising prices of essential commodities in Basirhat, killing a fifteen-year-old school student, Nurul Islam.

[2] Ghosh, S. (1988). ছবি তোলা: বাঙালির ফটোগ্রাফি–চর্চা [Taking Photographs: The Photographic Practices of Bengalis]. Ananda Publishers.

Siddhartha Ghosh, in this singular work on the history of photography in Bengal, studies a host of photographic institutions that came up in Calcutta during the late-nineteenth and the early twentieth century. Besides the more well-known clubs like the Photographic Society of Bengal and the Photographic Society of India, Ghosh surveys the following schools—

a) Calcutta School of Industrial Arts: Established in 1854 by the Society for the Promotion of Industrial Arts, the school began teaching photography in 1858 with the induction of the French surgeon-turned-photographer Jean Baptiste Oscar Mallitte as mentor. The institute is a precursor to the present-day Government College of Art and Craft, Calcutta.

b) Indian Art School: The school was founded around 1893-95 under the patronage of Jatindramohan Tagore and his son, Prodyot Coomar Tagore of the Pathuriaghata branch of the Tagore family. The artist, engraver, and photographer Manmathanath Chuckerbutty, famous for his book on photography in Bengali, ছায়া-বিজ্ঞান [Science of Shadows], was appointed as the principal.

c) Albert Temple of Science and School of Technical Arts: The school was established by the artist and writer Girindrakumar Dutta around the time of the Prince of Wales’ visit to India in 1875-76.

d) Jubilee Art Academy: Founded by Ranadaprasad (Das)Gupta at 92/2 Baithakkhana Road during the Golden Jubilee celebration of Queen Victoria’s accession in 1897, the school used to teach painting, modeling, sculpturing, and electroplating.

[3] Gujral, D. (2019). Painters with a Camera (1968/69): In search of an Indian photography exhibition. Object, 20 (20) pp. 33-58. https://student-journals.ucl.ac.uk/obj/article/id/551/. Accessed January 2, 2023.

[4] The Indian subsidiary of the Belgian-German multinational corporation Agfa-Gevaert, once highly popular for their range of analog cameras, films, and photographic papers. The company does not have a direct presence in India anymore.

[5] As a young student in the College of Engineering and Technology (which later became Jadavpur University in 1955) during 1929-33, Gopal Chandra Sen started his journey in engineering by repairing microphones in Mahatma Gandhi’s public meetings. After completing his studies at the University of Michigan, Sen came back to Calcutta and joined his alma mater as a faculty in the Mechanical Engineering department where he taught until retirement. In 1970, when a section of far-left students protested the holding of examinations in the university, Sen, as the interim vice-chancellor, acknowledged the students’ right to boycott examinations but refused to bow down to their demands for cancellation. On 30 December 1970, the last day of his tenure, as he was walking back to his home, he was murdered within the campus premises, presumably on account of his dissent.

[6] Almost all the JUPC salons during the 1980s and 1990s were held at either of these two galleries.

[7] Extracts from multiple “Foreword” sections in the contest catalog/salon souvenir from the 1980s.

[8] The Government of West Bengal and the Calcutta Municipal Corporation celebrated the city’s tercentenary on 24 August 1990, marking 300 years from the day Job Charnock, an administrator in the East India Company, is said to have landed somewhere near Nimtala Ghat, in present-day north Calcutta and received the lease of three adjacent villages—Sutanuti, Kalikata, and Gobindapur from the family of Sabarna Ray Chowdhury in 1690. However, a 2003 ruling of the Calcutta High Court, based on a report submitted by an academic committee of leading historians, observed that ‘a highly civilized society’ and ‘an important trading center’ had existed on the site much before Charnock set foot on the land, thereby obviating any historical truth to the claim of a definitive founding date.

[9] Singh, B. (2017). Shooting ace S. Paul was arguably India’s most awarded photographer. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/leisure/story/20170904-s-paul-photography-photojournalist-raghu-rai-1031172-2017-08-28. Accessed March 1, 2023.

Sourav Sil is a visual artist based in New Delhi. You can contact him at souravsil.work@gmail.com