Fortuitous Associations and Kin Networks

Marialaura Ghidini

Published on 20.5.2023

My first encounter with Bangalore was serendipitous. I first landed in the city from Delhi in 2013, for a four-month-long fellowship I was doing at SARAI/CSDS[1] as part of my PhD work on curatorial work online and digital curation with the research center CRUMBat the University of Sunderland in the UK. I was on a quest to meet artists and curators who were working in the field of digital and internet culture and was told that Bangalore was the place to explore.[2] It was known to be the tech hub of India that also housed independent spaces and cultural organizations working around technology, from research centers to artist-run spaces, and was the apt location for my research. My first lead was the event “World-Information City Bangalore” (2005), a program of events that took place across the city and addressed global issues of intellectual property and technology in conjunction with the changing urban environment.[3] Once there, I realized that the cultural landscape was much more diverse than I expected—besides artists and curators, research into digital cultures and the web was carried out by various professionals, such as lawyers, economists, and venture capitalists, among others. I began to informally interview people, meet curators at cafes, and do studio visits with artists to talk about their work. I also attended a conference, “Mediating Modernity in the 21st Century: Rethinking and Remembering”, at the Centre for Internet & Society organized by Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology. That was the beginning of a series of fortuitous associations that have connected me to the city through the years, and that have also broadened my research taking it toward a more interdisciplinary perspective.

After I returned to Delhi, the founder of T-A-J Residency (which ran from 2013 to 2017), artist Tara Kelton, invited me for a curatorial residency at their space in Bangalore. T-A-J had just opened with the aim to operate as a support structure for the development of artistic and cultural practices and thinking in Bangalore, acting as an activator of exchanges and conversations across fields of work—from visual art, design, and literature, to economy, law, and the sciences. So, I went back to the city a few months later—an occurrence that marked the beginning of a now ten-year-long collaboration, often unfolding across continents and various curatorial enterprises. At T-A-J we started to discuss ways of approaching discourses around digital and new media art and technological developments, not only in an interdisciplinary manner, but also from a local perspective—looking at their specificity rather than their universality. We began to brainstorm ideas for projects that would provide spaces for encountering this beyond the format of the gallery exhibition, and also for activities that would enable the artists in residence to have an outlet for their research and experiences. I then left Bangalore for the UK, with many new questions and possible projects to mull over.

At the time, I was running the online curatorial platform or-bits.com (from 2008 to 2015), and I was exploring ways of creating exhibitions around digital culture that would happen across spaces and formats of display. There was an opportunity to invite both Tara Kelton and Prayas Abhinav, with whom I previously collaborated in Delhi, to be part of a project that would take place in three ‘spaces’: online, in a reading room, on a rail platform in London (Banner Repeater), and in print (the UN-PUBLISHpublication series). The project, titled “Un-Published: Outsourced” (2013),[4] was produced in collaboration with the artist-run space Banner Repeater and the intention was to discuss the notion of outsourcing—something that we talked about much in Bangalore—in terms of its relationship with online platforms and users’ cultures. The two artists devised two consecutive solo site-specific projects that would unfold across these formats of engagement: Karizma and the Museum of Vestigial Desire, respectively. Starting with the premise that we regularly outsource services online, from ready-to-use display platforms to distributive tools, usually abandoning ourselves to what these services offer us, both artists’ projects questioned the pre-determined behavioral patterns emerging from online routines. Kelton did so by collaborating with digital service providers' workers to explore the relationship between the human action and the software interface, between personal choices and set parameters, in an age characterized by an increasing prominence of visual communication. Prayas, on the other hand, presented a museum that operated as a feed of text—a publishing entity without images that sought to enable access to residual particles of human desire cached at remote sites and made available locally via software on a web browser. This project allowed us to explore our collaboration and test out ideas about distribution and engagement in a context different from Bangalore, also via the mediation of another independent space dedicated to contemporary art.

Tara Kelton and I had similar questions related to ways of encountering art and were both interested in working outside the gallery space. After the or-bits.com collaboration, during which we witnessed commuters casually dropping by the Banner Repeater reading room, we started to work remotely on an exhibition project that would occur in an ‘ordinary place’. An electronics store, where people go to browse through objects surrounded by TV and computer screens, and to shop for home appliances and electronics, seemed an ideal place to work with. We then conceptualized the exhibition “The C(h)roma Show”[5] which, after months of negotiations with retail and store managers, was presented in the Indiranagar store of the retail chain Croma in December 2014. The idea was to bring digital art to the shop customers and to passersby.[6]

“The C(h)roma Show” took over the walls of display televisions inside the store for a week. Like a cabinet of curiosities, it presented videos, and sound- and web-based works by 41 national and international artists. Curatorially and artistically, we envisioned the exhibition as a way to question the supremacy of the multifunctional screen and the role and meaning of the desirable, hyperreal, and perfect digital image in an environment dedicated to consumption. The arrangement of the artworks was meant to provide, similar to the customers’ behaviors inside the shop, an experience of moving across the space and its aisles. The potential buyers were greeted with leaflets that had a map showing the location of the videos on the walls and a narrative to follow that addressed the relationship between the viewer/customer and the screen:

“…

[As you step into the shop television sets welcome you.]

Objects that convey the represented, that disseminate framed images played in a continuum.

[Hung in grid formations, they are placed to your left and to your right.]

They transmit hyperreal worlds, and want to be looked at, luring you in to their details.

[Walking closer to one of the formations, you find your way into the rhythm of what is displayed.]

The moving images of the Croma shop do not flicker, they show off what their host, the screen, is capable of: conveying the perfection of the represented.

[Your intent look moves across the grid, and you know that these moving images are of a different kind.]

Higher in quality, clarity, luminosity, here, the moving images are subsumed to the screen, often appearing more ‘real’ and vivid than the things in the world.

[This time they are confronting their plentiful host.]

This represented world is generic and abbreviated: a snippet of the real that shows you the desirable, the hyperreal and the perfect.

[And you are watching, no longer looking]

…”

Installation shots, The C(h)roma Show

The beauty of the project, for me, was also the kinds of relationships it enabled between customers and electronic devices, buyers and retail assistants, retail assistants and us, and passersby and contemporary art. It enabled a dialogue that unfolded at different levels and for different types of ‘consumers’.

While we were organizing “The C(h)roma Show”, the artist collective IOCOSE, from Italy, was in residency at T-A-J; with them we started to explore the layered tech-induced meta-narratives that were embedded in the city of Bangalore: from real estate advertisements to the fast-growing IT hub. As part of this exploration, we decided to present one edition of IOCOSE’s project “The NO TUBE Contest” (2014) in an internet cafe[7]—a small shop that offered a few workstations with computers connected to the internet in a small lane just off the main road of the Indiranagar area. The project functioned as a public contest and performance where the winner is the participant who finds the most valueless video on YouTube. A “NoTube” video—as opposed to YouTube videos that usually present a narrative and can be categorized—are purposeless, uncontextualized videos that contradict viewer’s expectations of a meaningful experience. Through these activities, the need to find ways to instigate renewed readings of the Bangalorean urban and sociocultural landscape became more evident to us. We wanted to enable the telling of stories from a personal and subjective perspective, while also being able to map artists’ readings of this layered urban landscape either because they lived or worked there.

Flyer, The NO TUBE Contest

The book series “Silicon Plateau”[8] was born that year, as a result of these experiences and conversations with other artists, curators, and researchers. The Centre for Internet & Society played a key role in this project; although they are dedicated to the study of the law and policies around the internet and emerging technologies, they understood the role of art as a vehicle to encourage discussions and supported this publishing endeavor since its inception. By the time the first volume of the series was released in 2015, I had moved to Bangalore to work as the artistic director of T-A-J Residency with Tara Kelton and joined Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology as a professor.

Excerpt from the book Art After Failure: An Artistic Manifesto from the City of Bangalore, IOCOSE

“Silicon Plateau Volume 1” explored the meta-narratives around the city of Bangalore and, in a way, some of its characteristics[9]—it also included IOCOSE’s first manifesto “Art After Failure: An Artistic Manifesto from the City of Bangalore”, which was written during their residency as a reflection on their practice that discussed the opportunity of reinvention created by the failure of technological developments.[10] Volume 2 (2018)[11] focused on the sharing economy and its unfolding in the urban landscape. The city continued to be a prominent feature of the narrative, but this second volume was more about people and social relationships, places lived in and ways of dwelling, the infrastructures that lie behind what can be seen on smartphone screens, and about human desires mediated by technology. In a way, there was more emphasis on the human element and its place in a fast-developing urban environment. We also strengthened our initial desire to work with an array of different practitioners—not only artists and curators, but also writers, anthropologists, and technologists with their different experiences and takes on digital and internet culture, as well as city life. Some contributors had been previous residents at T-A-J, as in the instance of artist Lucy Pawlak, who developed a fictional story from a workshop held at the residency,[12] and writer Anil Menon; some were people we crossed paths with, also serendipitously, and who inspired us in the making of the volume, such as researcher Sruthi Krishnan and anthropologists Mathangi Krishnamurthy and Nicole Rigillo.

Drawing on our earlier collaboration, Tara and I presented “Silicon Plateau” at Banner Repeater (2019) in London for which we devised the format of the ‘mini-interview’ on Instagram with the contributors of the book, while also displaying some contextual material in the reading room. This allowed the specific questions and experiences presented in the book to reach a new audience and be received in a different context. Recently, we also presented the project in Nottingham, as part of the exhibition and research program OTOKA (2022) curated by artist Candice Jacobs, who, a few years earlier, was in residency at Srishti Institute and with whom we had many research interests in common. There is a Volume 3 in the pipeline that we have restarted work on after the forced pause of the Covid-19 pandemic.

With my work at Srishti Institute, wherever possible, I tried to bring my network outside India to collaborate on projects or educational activities. Apart from Candice Jacobs, who developed and presented the work “Vernacular Equinox” (2018)—a VR installation that explored inhalation and exhalation as tools to understand people’s emotional state of being[13]—as part of the Srishti Interim program curated by Meena Vari, there were presentations by speakers invited for the CEMA Talks program (CEMA is The Centre for Experimental Media and Arts), such as the researcher Alessandro Ludovico, founder of the new media magazine Neural, and the artist duo Lundhal & Seitl. As part of a studio course in curatorial practice that I ran in 2018 with the students, we facilitated the event “Unknown Cloud” which took place at the National Centre of Biological Sciences.[14] The “Unknown Cloud” is a nomadic artwork that enables a collective experience via an app that asks the user to follow an immersive choreography with others, while another group of participants is connected at the same time in a different part of the world.

Unknown Cloud by Lundhal & Seitl at NCBS

Unknown Cloud by Lundhal & Seitl at NCBSOrganizing the event in the gardens of the campus of the research center turned out to be quite fascinating from a curatorial point of view—it allowed a varied group of people with different takes on art and collective experiences to come together: art and biology students, scientists and local residents, and art practitioners and other people working on campus. Again, this was possible because of fortuitous associations that happened beyond the conventional site of the gallery or the exhibition space, where most often engagement is regulated by the norms of behavior of the contemporary art world.

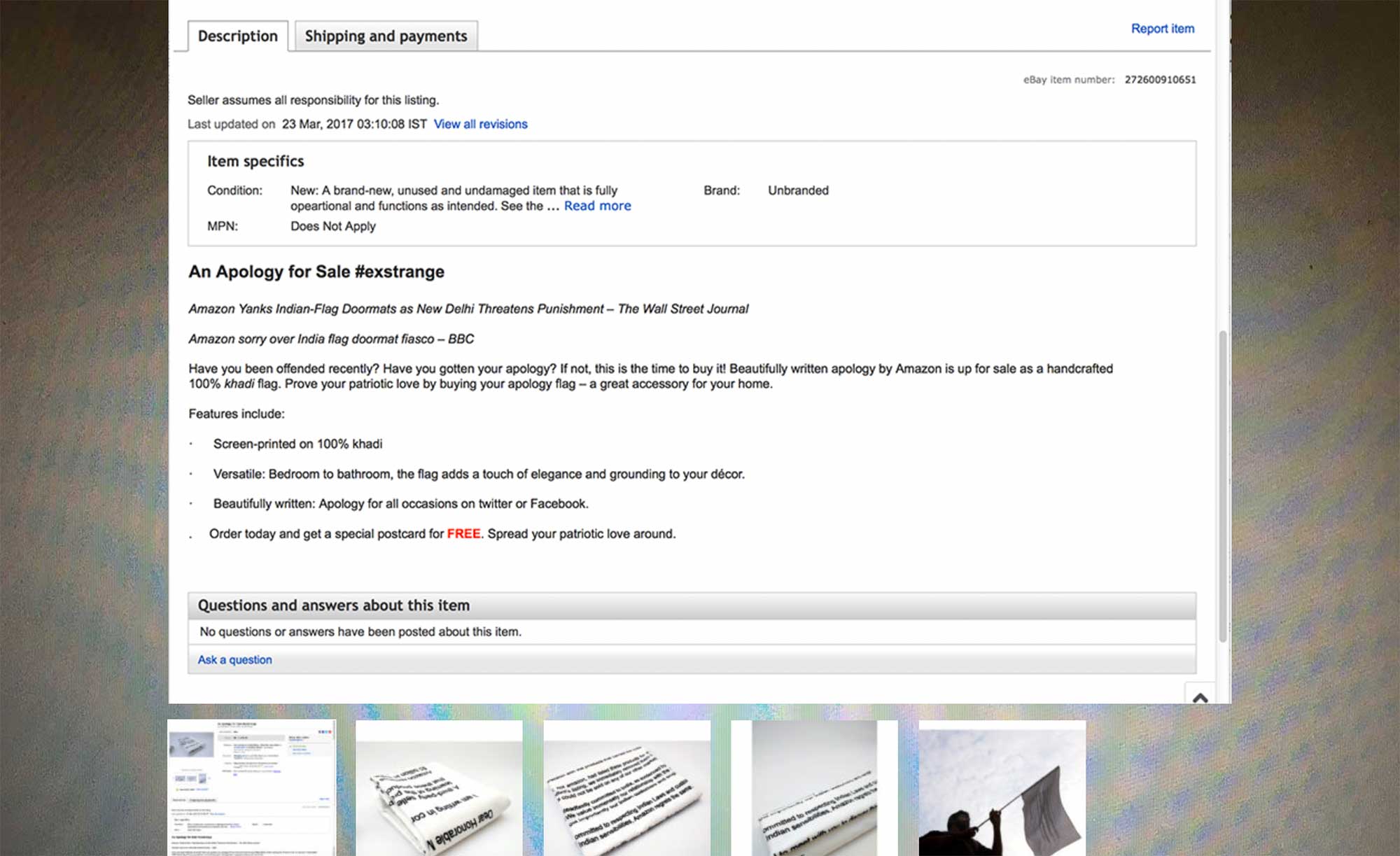

I also tried to bring some of my projects that happened elsewhere to India, as in the instance of #extrange (2017) which I co-curated with artist Rebekah Modrak,[15] who was also a resident at Srishti Institute. Taking place on eBay, this project explored the types of encounters and exchanges that could happen on an online marketplace and presented an artwork-auction daily for about three months. Apart from presenting artworks by invited artists and guest-curated projects by invited curators, the online exhibition was open to other artists and curators, including some of my ex-students, fellow faculty members, and other artists from India, such as Chinar Shah, who invited me to write this essay.

Screenshot, An Apology for Sale by Ajit Bhadoriya, Chinar Shah, Surabhi Vaya on #Exstrange

Screenshot, An Apology for Sale by Ajit Bhadoriya, Chinar Shah, Surabhi Vaya on #Exstrange Just before the pandemic, I started to collaborate with Walkin Studios on a proposal that would explore the notion of public domain in the city of Bangalore, using advertising as a medium of artistic expression. Although the project “Hacking the Public Domain” (2020), which we developed for the open call “560, Curated Artistic Engagements” by the India Foundation for the Arts, could not take place in its original form because it wasn’t funded, the concept was further developed by the Walkin Studios team later on and presented as a renewed project titled “Public Domain Garden” in 2022.[16] The project unfolded over time as a series of events online and offline—from the site of a shopping mall to that of a street in JP Nagar. Although our paths had crossed before the writing of that proposal, we found the chance then to share our curatorial ideas at a seminar titled “Technology for the Arts” (2019), which was organized by ArtIllume in Bangalore. A few months after the seminar, there was the first nation-wide lockdown (2020), and with the founder of Walkin Studios, Vivek Chockalingam, we came up with a project that would sustain our minds while stuck in our homes. This was because we found ourselves facing an information overload, full of questions and lacking answers to them, and were wondering about the role of our work and our place in the world. We looked for a way to connect with other people in our community—artists, writers, researchers, and creatives—so that we could wonder together with them about what was going on. We tapped into our network of fellow artists and curators and previous collaborators and started “Walkin the Portal” (2020),[17] a series of 15-minute live conversations on Instagram that became a downloadable publication a few months after. The publication includes a record of the conversations that happened online, and our attempt to document what was going on outside the spaces we were locked in.

Excerpt from the publication Walkin the Portal

Excerpt from the publication Walkin the Portal

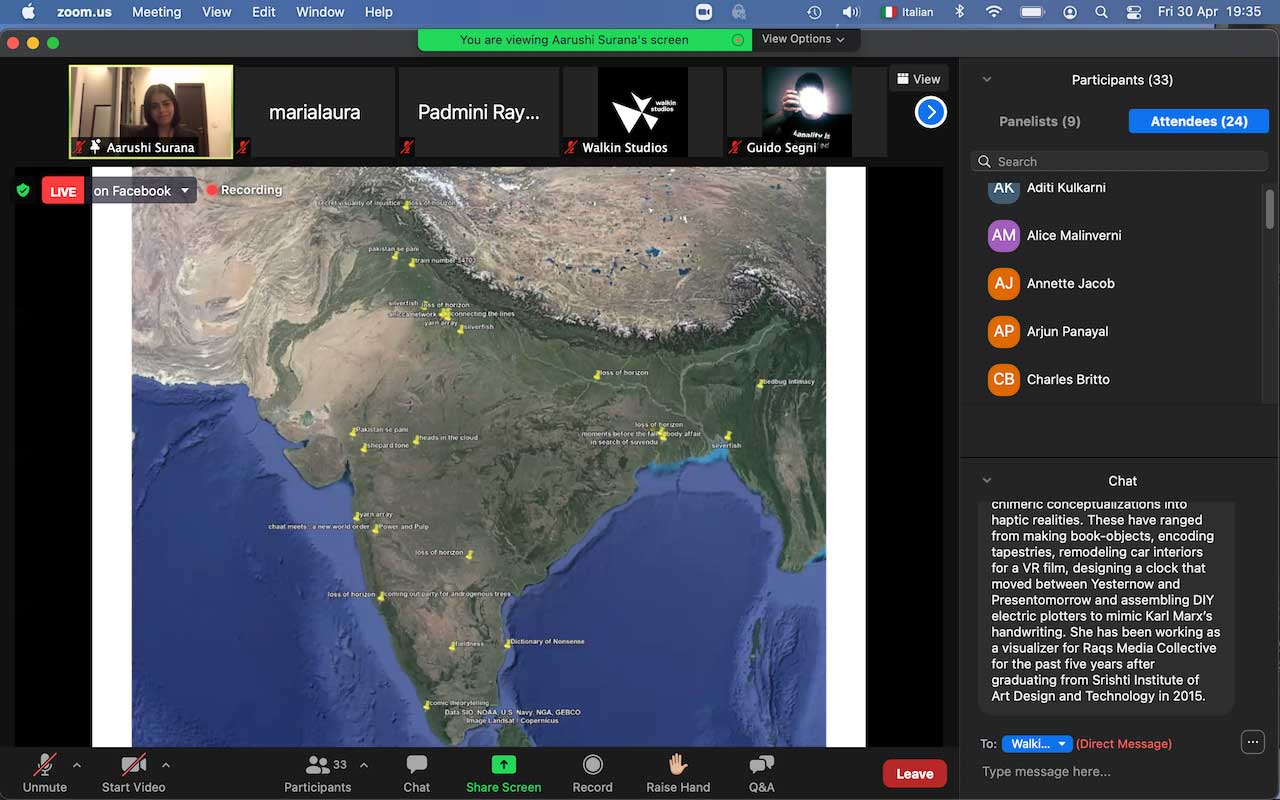

Screenshot of presentation during the webinar Curating on the Web by Kaushal Sapre and Aarushi Surana

Over th past three years, I have mostly been in Italy, but have had the opportunity to continue some of the collaborations I described above, from the webinar “Curating on the Web” (2021)[18] organized in collaboration with Walkin Studios to the research and development for “Silicon Plateau Vol. 3” with Tara Kelton. I have had the chance to look back at the past ten years of my relationship with Bangalore, and to reflect on the impact that fortuitous associations have had on my curatorial practice. Many chance encounters have enabled me to make new discoveries and take unpredictable turns, but most of all they have allowed the formation of networks and kinships that go beyond me and my practice and move fluidly across spaces, geographical areas, forms of engagement, and contexts of work. This, I believe, has also been possible because of the mode of work surrounding independent spaces and initiatives, with their genuine interest in community building, in creating engagement across various social groups, in encouraging dialogue, and in caring for creating sustainable spaces for practitioners and their publics.

[1] As part of my time at SARAI/CSDS, I co-organized with Sarah Cook (CRUMB, University of Sunderland) the workshop “Hybrid Curatorial Models: Producing and Publishing in-between Offline and Online Dimensions” (2013). As guest speakers we invited artist Prayas Abhinav, Joy Chatterjee of Sarai's Cybermohalla, and Shankar Barua of the html magazine The IDEA with whom we discussed curating across online and offline distributive platforms and inter-media publishing.

[2] I thank Sumandro Chattapadhyay, then affiliated with SARAI/CSDS, for his suggestion to visit Bangalore during an insightful chat we had about my research goals in the leafy garden surrounding the SARAI/CSDS building.

[3] The program was organized by SARAI/CSDS, the Alternative Law Forum (ALF) in Bangalore, the Institute of New Culture Technologies/t0 in Vienna, and the Waag Society in Amsterdam, http://world-information.org/wio/program/bangalore.

[4] For more information about the project, see: https://www.or-bits.com/outsourced.php and https://www.bannerrepeater.org/orbits-un-publish-outsourced.

[5] The exhibition was titled after both the retail chain and Derek Jarman’s work “Chroma. A Book of Color” (1994), a meditation on the color spectrum whereby the author argues that color perception is changed by the context in which it is encountered.

[6] For more information about the project, see: https://thechromashow.tumblr.com/.

[7] For more information, see: https://cis-india.org/internet-governance/events/iocose-talk-at-cis.

[8] For more information and to download a digital copy of the books, see: https://siliconplateau.info/.

[9] The contributors of the book, published by the Centre for Internet & Society are: Abhishek Hazra, IOCOSE, Tara Kelton, Anil Menon, Achal Prabhala, Sunita Prasad, Sreshta Rit Premnath, Renuka Rajiv, Anja Gollor & Mirko Merkel, and Christoph Schäfer.

[10] The manifesto was accompanied by a photographic series titled “Elevated Bangalore” which, in the words of IOCOSE, acted as a “proposal for an art after failure”. See also: https://iocose.org/works/elevated-bangalore/.

[11] The contributors of the book, published by the Institute of Network Cultures in collaboration with The Centre for Internet & Society, are: Sunil Abraham and Aasavri Rai, Yogesh Barve, Deepa Bhasthi, Carla Duffett, Furqan Jawed, Vir Kashyap, Saudha Kasim, Qusai Kathawala, Clay Kelton, Tara Kelton, Mathangi Krishnamurthy, Sruthi Krishnan, Vandana Menon, Lucy Pawlak, Nicole Rigillo, Yashas Shetty, and Mariam Suhail.

[12] The workshop was titled “SPIES SPY ON SPIES” and took place on 6-7 February 2016. For more information, see: https://t-a-j.in/E-V-E-N-T-S.

[13]For more information, see: http://meaningfulmeaninglessness.info/index.php?/online/the-vernal-equinox/.

[14] For a documentation of the project, see the video produced by Srishti Films: https://vimeo.com/257381409.

[15] For more information, see: https://exstrange.com/.

[16] For more information, see: http://publicdomain.garden/.

[17] The people we interviewed are: Meenakshi Thirukode, Anil Menon, Sultana Zana, Rahul Giri, IOCOSE, Jennifer Hodgson, Gayatri Kodikal, Akshat Nauriyal, Nick Tobier, Tatiana Bazzichelli, Mathangi Krishnamurty, Andrea Ulrich, Ali Akbar Mehta, Harun Morrison, Josephine Simone, and Suvani Suri. To download a copy of the publication, see: https://www.walkinstudios.com/files/ugd/7809135b71c388ba1f414cb7f706a8075b0565.pdf.

[18] For more information, see: https://www.curating.online/event/curating-on-the-web-subverting-the-mechanisms-and-traditional-models-of-producing-and-distributing-contemporary-art-and-culture/.

Marialaura Ghidini is a curator whose work explores the intersections between art, technology and society. Interested in working with various curatorial formats outside the gallery, Marialaura thinks of exhibitions as ways of telling stories that exist across spaces and amongst people. Since her PhD (2015) she has researched the filed of curating on the web, contributing to books and creating archives. Currently, she works as a curatorial consultant, also under the moniker ://ftp.