Each File is a Person (Part I)

An Interview with T. Jayashree and Siddarth Ganesh from the

QAMRA (Queer Archive of Memory, Reflection, and Activism) Archival Project at NLSIU, Bengaluru.

Samira Bose

Published on 15.12.2023

In the first segment of a two-part interview, Samira Bose speaks with T. Jayashree and Siddarth Ganesh from QAMRA about self-organizing an independent archive, the complication of categorizing archival materials, and their dialogue with other like-minded projects across the global south.

In the second part, they will share about intergenerational conversations, attuning to affect and feeling in archives, and their shift in 2021 from a residential space to the campus at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

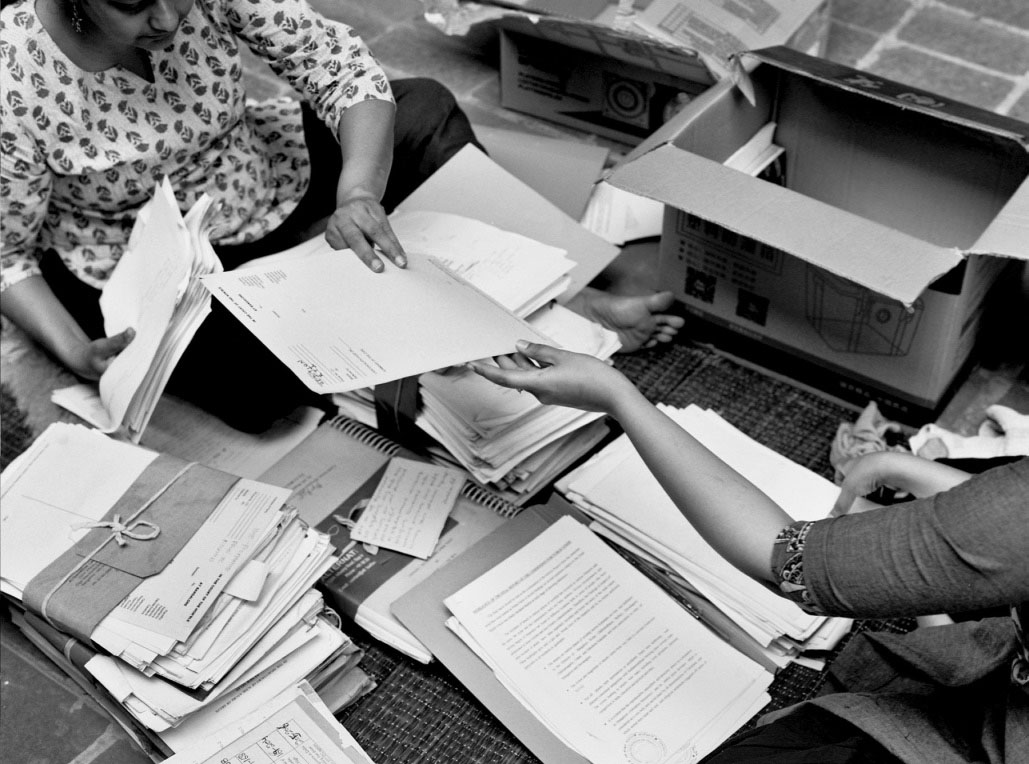

Co-founders T. Jayashree and Deeptha Rao working with the Sec. 377 IPC courtroom papers. Source: Marc Ohrem-Leclef.

Samira Bose (SB): It may seem like I’m going to be posing questions in a linear way, but that’s not going to be the case. However, I do really want to begin by asking about the moment when QAMRA was an idea—what was the initial impulse that led you to conceive of and self-organize towards the archive?

T. Jayashree (JT): It’s interesting that we are talking about this today because the Supreme Court hearing on marriage equality is going to begin, and it is the same Supreme Court that is in a way the reason we all got together.

The Section 377 litigation process started sometime in 2000 when the initial Naz petition was filed in Delhi High Court and then, in 2009, we had this grand victory, a fantastic judgment that we got. It was immediately contested in the Supreme Court and the hearings began in 2012. This was a hearing where for the first time three religious leaders came together on one platform and opposed the 2009 judgment, which basically decriminalized homosexuality between two consenting adults in the privacy of their home. It also spoke about the right to dignity, the right to life, and the right to privacy. So, it was very quick—the way they got together, the hearing itself. Many, many people intervened in that petition. There was a whole gamut of people coming from different walks of life saying that this 2009 judgment should stay.

The 2012 hearing was very bizarre, and whoever was in New Delhi and in the court were very ambivalent about what was going on—the way the court phrased questions was very disturbing, even as we were riding high on the Delhi High Court victory. There was this conversation that would go on asking, “Where is this going?” And that’s when a lot of us that were kind of in the periphery and seeing what was happening felt that this whole thing has to be documented—‘this’ being the impressions of what happened within the court, because you can’t record inside the courtroom. We would receive copious notes that Siddharth Narrain used to email us every evening after the hearing happened. We all felt a sense of dejection, and were like, “Why are these judges asking such questions?” The difference between the Delhi High Court and Supreme Court was that in the latter they just were looking at a very narrow interpretation and kept harping on about the idea of the sexual act between two men. To put it crudely, that’s what they were asking, which was very disturbing. It was at this time that we said, OK, we need to somehow document this process.

Initially the idea was to just record these lawyers—what they were saying, what they saw, and their own thoughts and impressions. Then we realized there were so many interveners. So, then I started recording some of the petitioners. I still haven’t interviewed all the petitioners, there’s no funding for any of these things, and at that point of time, we were not even thinking in terms of the archive or anything. We just said we will document what people were saying because one of the questions the two-judge bench kept asking was, “Who are ‘these’ people? Where are ‘they’?” Now, this is a double-edged sword when it came to queer lives at that time because there was a criminalization of this act, and a lot of people were underground. You could not come out and say yes, I am so and so, even though petitioners in Naz did—like Gautam Bhan was the first one to put his name and to say I am so and so and this is how I live my life—and one didn’t know which way it would go. In these petitions you need to also give your address and details about yourself. What do we do now? If we don’t tell the story, then we don’t exist. If we tell our story, we don’t know what the repercussions are going to be, and this has always been the dilemma with our lives, right?

We started documenting on video, not realizing where it’s going or what’s going to happen. Then, in 2013, just before the judgment came out, there was a three-day queer archiving workshop that took place in Bangalore, where we were trying to understand that if we have to archive queer lives, how do we do this? And this workshop was supported by IDS (Institute of Development Studies) in the UK, so they could invite different people from all over the country. There were other archivists, like the India Memory Project, CS Lakshmi’s SPARROW (Sound and Picture Archives for Research on Women), individuals who had been archiving mostly in digital media, and a lot of queer folks who came. You have to understand that people collect things. One of the interesting things that we learned from the activists was that right through the 60s and 70s, people have been looking for references in images, writings…is there somewhere, something that they could relate to? People have collected a lot of stuff like magazine articles, even advertisements and pictures.

The 2013 judgment came three months later, where homosexuality was recriminalized, and we realized that we will not be able to do anything. What we decided then was that we would all just keep the materials with ourselves and not destroy anything, and that there’s a certain amount of value to this. People also started collecting more actively and it also became more important because the judgment that came said this is a “minuscule minority,” which meant that we had to counter this, saying we are not minuscule, there are a whole lot of us. And in any case, even if you’re one person, in a democracy your rights have to be protected, right? And you have a right to your life. The documentation continued, including my own interviews.

Then, around 2017, which was the tenth year of the first pride in Bangalore, we were all just looking at the material and I had already started feeling and asking, “Where will all this go?” We also realized that video material is very difficult to upload online, and maintaining it costs a lot of money, even if you have full consent and all of those things. We were wondering how we could give shape to this archive, and I specifically wanted the material to go out of my studio space.

In any case, in that tenth pride, they wanted to see the footage of the first pride, which I had filmed. It was on tape, which we digitized, and then it suddenly struck me that even though it was 10 years ago, there is so much material which is very important for what’s happening today. So, I just put together a few clips saying, where were we then and where are we now?

We screened this thing at the Alternative Law Forum (ALF) and talked about some of the people from the first protests and it just went on from there. We showed some of the parents who were the petitioners and that was very moving because, you know, you don’t really know who these people, who are part of this petition, are. These are really ordinary folks—mothers and fathers, who put their names.

Just before that, Ponni Arasu—queer feminist activist, lawyer, historian, and who now lives in Sri Lanka, one of the advisors of QAMRA—happened to visit my studio and said, “Oh, you have two rooms. Why don’t you just start cataloging. Why are you waiting for someone else to do it? You just do it.” I said that that’s a good idea because it’s my material—I might as well.

T. Jayashree speaking at the screening

at the Alternative Law Forum, 28 November 2017. Source: Nidhishree Venugopal.

T. Jayashree speaking at the screening

at the Alternative Law Forum, 28 November 2017. Source: Nidhishree Venugopal. There were some interns hanging around in my studio and then we started literally saying there should be memory, there should be activism, there should be reflection. Then we put all the letters together, and I was very excited when it was QAMRA because it also means the Hindi and Urdu word “kamara” which means a room, a closet. It also has some resonance to camera.

After that, the 2018 judgment also came within six months, so 377 was again read down and then we felt the court case was over. The lawyers in Delhi said now you please take all this material to Bangalore, and they sent some 6-7 cartons by roadways.

Even before the judgment had come out, Sangama, which is the NGO that has been working for the last 23 years in Bangalore, had had a very robust documentation center for 14 years. They did everyday documentation of newspaper and magazine clippings and various things, and also their own organizational documentation. They said just take all this material.

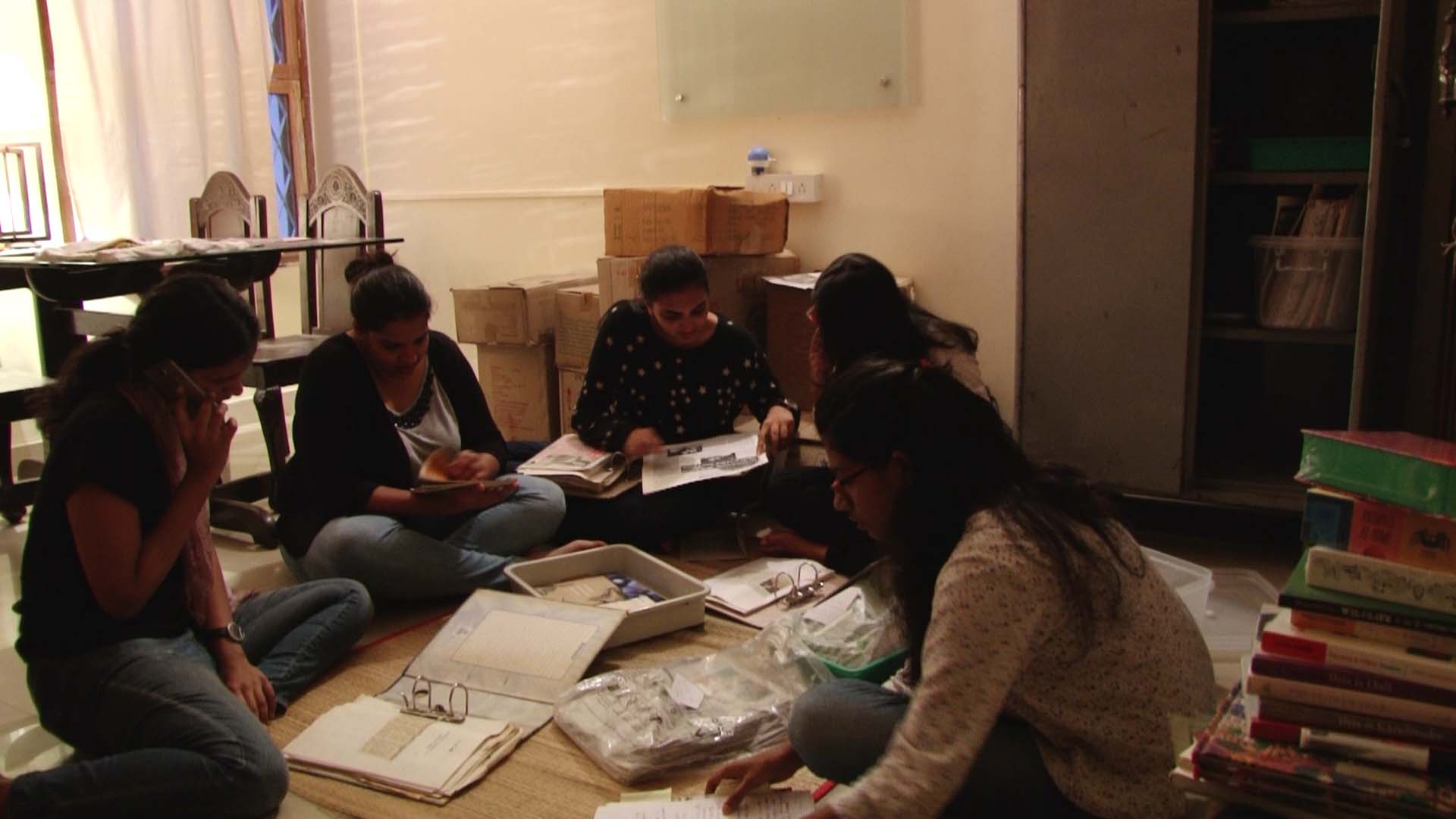

Volunteers from St. Joseph’s College

sorting through the newspaper clippings in the Sangama Collection. Source:

QAMRA Archival Project, NLSIU.

Volunteers from St. Joseph’s College

sorting through the newspaper clippings in the Sangama Collection. Source:

QAMRA Archival Project, NLSIU. We got these three collections, which form our founding collection. I got all of this in my studio space and we started—we had a whole bunch of volunteers from St. Joseph’s College, and many others. So, we started logging on to an Excel sheet, that was our first thing. Then in 2019, Vivek Divan, Arvind Narrain, and I went to talk about Siddhartha Gautam’s papers. Siddhartha Gautam was one of the people behind the booklet Less Than Gay, which is one of the first books or any kind of document to talk about homosexuality in India. It was published in 1991 November, and in 1992 January he passed away.[1]

In that process we visited (I think) nine archives over three days—university archives and independent archives, queer archives as well. We learnt about how materials are kept, cataloged, and presented and how archives are now being revitalized. They’re seen as a different, very active kind of space which immediately made sense to us because we also always thought about QAMRA as a living archive. It has to be used and is not something that has to be put in a cupboard. We are not going to be the gatekeepers of stuff, keeping material and all of those things. And the other thing—we quickly realized that our materials also have people who are still living.

To summarize, what we have is more or less public history of the litigation process, and a lot of personal reflection and reminiscence in terms of the oral history interviews and then, of course, there’s a whole lot of ephemera that we have. But what we still need to get is a lot of the private work, and also even these activists who’ve been working on this issue for so many years: their thought process and how did they function in a certain milieu, because a lot of this activism has come out of the feminist movement, it’s come out of the labor movement, so it has those intersections, right? I mean you don’t just become a queer activist one day, right? You also have a lot of other areas which you are engaged with, and it was also very different in India at that time. We really need to document those experiences of all these people.

Anyway, that’s how we started, slowly, and then Siddarth joined us in 2020. We started cataloging. And then we started engaging with other groups and then waves of COVID happened, and the funding landscape changed. Nobody funds archives, right? Especially what funders don’t realize is that we need day-to-day working people who nurture the materials. When users come in, ready to use the materials, we have to really resist saying we first need to get consent. We realized that the only way to go forward is to be part of an educational institution, where we are now.

SB: Thanks so much Jayashree for taking us back to the beginning and giving us a kind of overview, which can now help us get more deeply into some of the threads. Actually, one of the things that I wanted to ask about was that it’s interesting that independent archives begin at that moment when there’s a decision to begin to catalog material that might already be there. I’ve also wondered how then does one arrive at categorization when you’re working in an independent or self-organized capacity, and the complication of categorizing materials, especially in a queer archive, and how you’ve been thinking about it.

JT: Siddarth will explain it to you, but I just want to add one thing before that because they were not part of QAMRA when we set it up in 2017. As I said, in 2018, I went to Lucknow to meet Saleem Kidwai who is no longer with us. He was a historian, and also co-author of this very seminal book called ‘Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History’ with Ruth Vanita. He had tried to set up a queer archive called ‘Documentation, Archive, Research, Education’ in Delhi in 1995 or 1994. It didn’t take off, and we in fact found a pamphlet of that in the archive, in one of our collections. He talked to me about what went on, and he had a lot of ideas and tips to give us. One of the things he said is that we need to stick to dates—just go chronologically, and don’t worry about anything else because dates are very, very important; follow that with all the material you have.

Siddarth Ganesh (SG): Cataloging at QAMRA has been a process that we keep learning from. It’s not a process that we’ve just stuck to without questioning it and ourselves while cataloging our material. Each collection is so unique and has such diverse kinds of material from such different origins, each asks for a specific way of cataloging it. We follow a sort of logic that the material and the collection itself makes evident more than us imposing a logic. And this is a decision that we take, as archivists, on an as per needed basis.

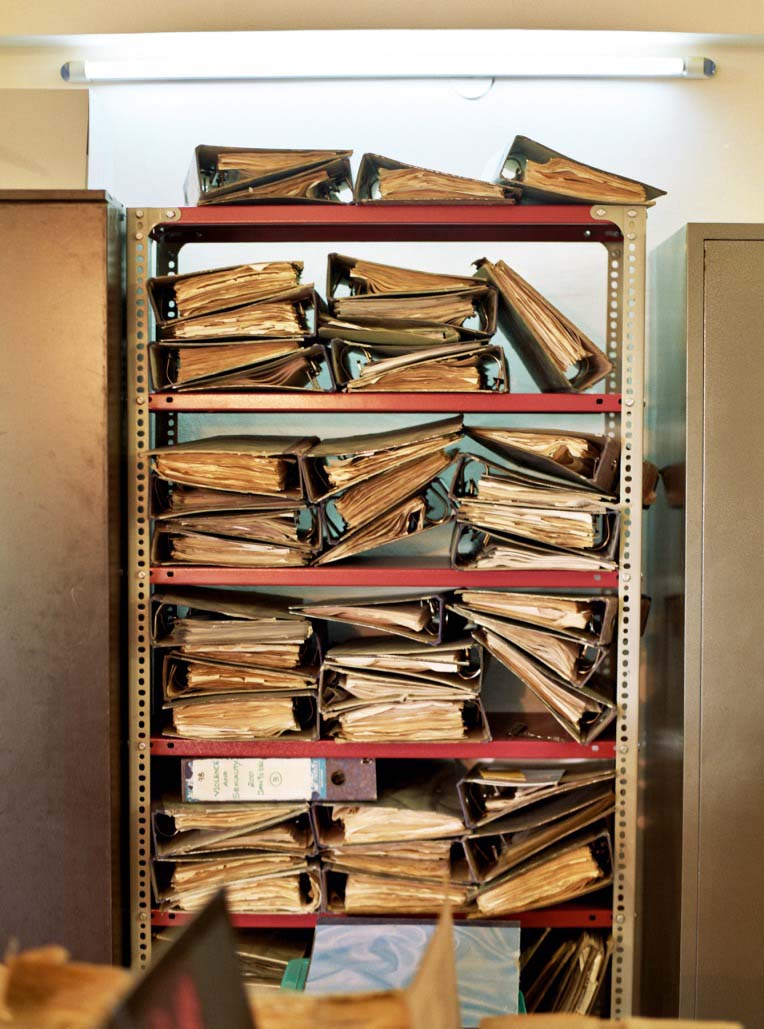

There is ‘original order,’ in which you organize the material in the manner in which the collection comes—you change nothing. Then there is ‘imposed order,’ wherein the archivist—after sorting through and working with the collection—realizes that it doesn’t make sense, and it needs to be more easily accessible, and then we spend more time on it to figure it out. This method is what we decided to follow for the Sangama Collection, which is one of the biggest collections in sheer volume that we have, and it came to us in a big jumble of folders and files. There are two main components to this collection—one is the documentation project that Sangama had for 16 years, and the organizational archives that they have given us. These came to us very jumbled. So, in the same plastic sleeves you’ll have, you know, some brochures or pamphlets or emails, and you’ll have some newspaper clippings. When you find a file like this, there are different ways of trying to understand it. One is that it is just a jumble of different documents, where you look at the dates and what is being covered and you can understand in that way. Sometimes, it can also be about an episode, about an event or an incident that happened, which can be preserved using different kinds of documents. So, you’re not completely keeping the documents separately by their nature. You’re allowing for these organic links that are already there in the collection to surface, and how we’re curating it preserves a little bit of the original donor’s intention—in this case, Sangama—as an organization and their relationship with their own materials, which adds to the story of the organization and the collection. In some collections, such as the Maya Sharma and Indra Pathak Collection from Baroda, we follow both the principles.

Some folders from the Sangama Collection before being sorted through and cataloged. Source: Marc Ohrem-Leclef.

Right, so this is about categorizing but when it comes to creating a catalog, then categorizing is also a little bit more “meta” (chuckles). Sorry for the bad joke about metadata, but, if we take the example of language in the archive—initially we had thought that especially with the Sangama newspaper clippings, it might be a good idea to separate and catalog them by language because we have them in English, Kannada, Tamil, Hindi, some in Telugu, some even in Gujarati, and quite a few in Malayalam. Not all volunteers can work across these languages, so we thought, let’s focus on them separately by language. And even though that is how the work physically continues, where whoever can work with those languages comes and starts updating our catalogs, we have taken a decision to not keep them separately in separate boxes. In the digital catalog, and in the final arrangement of the documentation project in the archive, there will be no linguistic distinctions. We came to this decision after many conversations with our Advisory Board because this is one way of decolonizing the archive and decolonizing systems of knowledge curation and production as well, and we don’t want to replicate colonial divisions, linguistic divisions that then lead to further divisions and political situations in our own organizational system, so it’s a practical approach, but also epistemic and political at the same time. Jayashree, do you want to add something?

JT: I just wanted to add one more sentence to say that the other positive thing of doing this across language is that especially when you look at newspapers and how newspapers report on queer issues or they continue to, and when you look at different languages at the same time, you get a different sense of how society was thinking around that time. And we’ve had students work with it, and it’s been fascinating to see how the same things are perceived locally.

SG: And also, to add to this again, because it can come under categorization, is that there are different categories of access as well in the archive. We are a public archive. We want to have access to our collections without a paywall where anybody can say, hey, I’m interested, I want to come see this material. We’re open for them, but what we’ve realized after working with such sensitive material in our collections is that public access does not necessarily mean open access. And so, we work with the people who are giving us the material to truly explore the limits of consent, privacy, data storage, or data deletion issues that they might have with their material coming into the archive, and only after those conversations with them decide how much of which collection can be opened up.

It then gives you different layers of access, where some newspaper clippings are completely open and public access because it’s already in the public domain. But if you take, say, sensitive emails exchanged between organizations during a collaborative project that they were having, that cannot be made open access because sometimes you have fights happening between the two, and preserving the story of that can leave an archive like ours open to legal actions under defamation or slander. So, we’re very conscious with the material we have and how much of which kind to open up.

And this then feeds back into this conversation of the nature of the work we do. Is it just to make these documents openly and publicly accessible, or is there more to archiving than just conceptualizing “use” for the collections? I think sometimes this is a little bit of a problematic word in the archive, because it’s very unidirectional. I think it’s beneficial to think of it more bidirectionally or multi-directionally, where you’re thinking of preservation of the material beyond just its academic research or practical uses, but for preservation itself. And it’s to say that we need to remember that certain things that have happened don’t matter only if somebody comes and writes an academic essay on this at the end of the day, but different people give us different things so that some of these things are remembered.

SB: I’d love to discuss what’s been brought up about language, and I’ll get to that in a moment. I was made aware that you are having these ongoing dialogues as an independent archive with similar projects and some of them that I had seen wereInterference Archive in Brooklyn, with SPARROW in Mumbai or GALA in Johannesburg.

Could you give some examples of what you’re learning from each other? And I’m actually speaking specifically about evolving methodologies of archiving because exactly as you both have been saying, you are an independent archive working with limited resources and infrastructures in varied political climates. Are there some things that you’ve learned from these dialogues that you’ve maybe applied within the archive?

JT: We visited the Interference Archive in New York city, and we really hope we could have set up something like that here in Bangalore with QAMRA, but there is the issue of the political situation now and resources. One thing is also about culture and space for all of this. I mean, Joan Nestle was a schoolteacher who started the Lesbian Herstory Archives in her living room. And that was the space where people would come and hang out, and the archive also becomes a safe space for people, and so has this dual role.

One of the things that we learned from all of these, especially the Schwules Museum in Berlin, was that even though archiving seems like a solo project, where it’s one person’s obsession with the material, it really requires a whole community to pitch in. We kept talking about how we really need to work with volunteers because people have to come and feel free to be with the material and each of them brings in new perspectives to the material, and that’s how an archive remains alive. Otherwise they’ll become just like state archives.

This may be interesting for you, because what we saw in the Interference Archive is that people just come in, open the drawers, they remove things, they look at it, and put it back. They don’t even have an archivist, they just have one volunteer who’s there every afternoon, and they take turns to be there. It’s truly a community space and it’s not a queer archive, it’s actually a community archive. It started with housing rights in Brooklyn, but then they have some queer material and they have an exhibition space.

On the other hand, the Schwules Museum was very specifically a “gay museum” set up in the late 70s, again starting with housing rights in Berlin, and people who are spearheading this movement were also part of the civil rights movement and all. At that time, the word ‘gay’ was very popular, so they call it ‘gay museum’ but when we went there in 2018, there was a lesbian curator, and she was trying to bring in all kinds of other things into it—there was a huge exhibition on trans lives that was going on there, on immigrant issues, and various things. Somebody had donated that building, where they can be housed for 90 years. That’s another thing for a physical archive—a permanent space is very important; you can’t just keep moving.

I mean, we’ve moved three times up and down from my studio because of the money situation—we moved from one room to half a room to three rooms. In India, we still don’t value archives in that sense, so nobody outright funds you for archiving. And yet, people are collecting, and have cupboards full of materials which they have kept for years and years. So, despite it all, the work continues.

How do we give a shape and bring it all together in one space and start having these conversations, rather than working in silos and asking, OK, what happens to my materials after I go?

We learned a lot from going to these spaces, but in any case, North America has huge institutional university supports and there are archives that are now very actively seeking core material from India—they will buy it, they will house it. One of our core philosophies at QAMRA is that we don’t buy acquisitions. I mean, we don’t have money also, but even if we had money, we would not. What we would help with is in digitizing or couriering and transport, but other than that it has to be freely and willfully given to us. Also, if the donor doesn’t want to make their collection public, we are fine with it. We will keep it in safe custody.

Till date we are only funded by individuals and friends who have supported us. None of this material is acquired by purchase, and when people do come to use it for reference, there is no entry fee, but if you want to reproduce something we have some kind of a contribution that we ask for. We haven’t done that till now, but we are thinking that we should do that, because that’s the only way we can survive. These are certain things that we learned from looking at these archives and spending time with them, and it was really fascinating how much time people gave us to speak about various things.

We also met with The South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), which basically takes material, digitizes everything, uploads it, and returns the originals. They collect anything and everything to do with South Asians in America, which is another way of doing things.

What we observed in Europe that was interesting was that community archives are housing materials from queer archives. And then you have very specific queer archives—they also talked about costs and how you run an archive, what should be your administrative systems, what works, what doesn’t work; and the Europeans are very, very aware of what happened during the Nazi era, which is still fresh. Even though they work with the government, they’re very careful about what material they are putting out and where they are putting the materials.

We are very close to GALA Queer Archive at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, dealing with similar issues in terms of race and caste. We have had some dialogue with them, and one positive thing about COVID was that we can do these Zoom conversations. It’s how we were able to have the recent public program with Joan Nestle and her group. It was really fascinating to hear them. She’s 82 and she’s still full of beans, and she has so much to talk about. We are hoping to have further conversations with folks from GALA, and all of these places. We’re also learning and thinking about digital platforms. It’s literally been a year that we’ve been functioning without any interruption, so we now need to figure out which direction we will go, how much can we achieve, because we only have two full-time people right now, and a whole lot of volunteers who helped us through all of these years.

SG: One particular kind of archiving that I gravitate towards—and I try to reconcile with the work that I do at QAMRA—is the work with archives of indigenous communities. The frameworks they employ in how they look at community knowledge for me is very interesting because, while working in the archive here, I realized that what we’re doing is actually like cultural work—it’s memory work, right? We have lots of things about activism. We also have a lot that enters the personal, the interpersonal, the social. So at QAMRA, then, through the collections we have, we are consciously raising these questions about what constitutes queer culture in India, what are its different aspects? Where are the communities? It becomes like socio-ethno-archeo-historical…very multidisciplinary that way. Why I’m particularly drawn towards archives of indigenous communities is because they look at community knowledge as a unique knowledge structure, and I’m trying to see how that can be adapted in working with queer community knowledge, essentially because at its heart—and this is built on what Jayashree was also just talking about in terms of ownership—we don’t consider ourselves as the owners of any of this material. The owners have very graciously given it to us to preserve, and thus we are the custodians of our collections, but we don’t own it…the technical ownership of this is the community at large, right?

If you take the example of the pride photos from 2008, it was a very important community event. It’s not just the Pride Organizing Committee which gave us those photos, who hold a stake in the conversation, but there are many more stakeholders as well—communities, organizations, individuals. So I keep going back to those frameworks to try to expand and understand archiving as a way of empowering marginalized communities through enabling memory support structures, access to information and data in ways that they’re doing in other places, so yeah, adapting it to the queer framework, essentially.

[1] Siddharth Gautam suffered from cancer and passed away when he was only 27 years old. His sisters and friends kept his memory alive, and they were the first petitioners to contest 377 in 1994. So this group was called ABVA (AIDS Bhedhav Virodhi Andolan) and by 2000, that petition was thrown out because there was no show. The activism around it had fizzled. But prior to his passing away and the publication, there’s a whole lot of work that Siddhartha Gautam had done, and he was a quintessential archivist—he had collected so much stuff, he had written so much stuff. And his sister subsequently preserved all of this. She’s kept it for 30 years and she showed that material to us and we had kind of cataloged it for them, for the family, and then Yale University gave a posthumous award to Siddhartha Gautam, and all of us—Arvind, Vivek Divan, myself, his sisters Anuja Gupta and Sujata Winfield were all there to think about Siddhartha Gautam’s legacy and work and how it impacted the court case and subsequent litigation process.

The QAMRA Archival Project at NLSIU, Bengaluru, is a multimedia archival project which aims to chronicle and preserve the stories of communities marginalized on the basis of gender and sexuality in India. The Queer Archive for Memory, Reflection and Activism (QAMRA) aims to aid efforts in queer rights advocacy through archival activism, acting as a resource base for activists, students, educators, artists, and scholars working in the areas of gender and sexuality. As a repository of narratives, its aim is to enable and further conversations around the history, present, and future of the Indian LGBTQIA+ community. Read more about the archive’s collections at www.qamra.in.Samira Bose is Curator at Asia Art Archive in India, New Delhi, where she conceptualizes exhibitions, workshops, and discursive programs to activate archival collections. Most recently, she has worked on traveling library projects and a series of Inter-Archives Conversations.

Samira Bose is Curator at Asia Art Archive in India, New Delhi, where she conceptualizes exhibitions, workshops, and discursive programs to activate archival collections. Most recently, she has worked on traveling library projects and a series of Inter-Archives Conversations.

T. Jayashree is an award-winning independent filmmaker based in Bangalore. Trained in video for development from CENDIT, New Delhi, Jayashree has written, produced, and directed for international television, radio, feature, and documentary films. Her work has focused on the intersection of gender, sexuality, law, and public health. The bulk of her unedited video documentation around sexuality issues and the legal journey to decriminalize homosexuality in India form the founding collection of the Queer Archive for Memory, Reflection and Activism (QAMRA) which she co-founded in 2017.

Siddarth Ganesh is an archivist and aspiring queer historian based out of Bangalore. They have a master’s degree from Université Grenoble-Alpes, with a specialization in the queer history of Bangalore and Social Movement Theory. They are a part of CSMR, involved in organizing Namma Pride in Karnataka. Their areas of academic curiosity include critical geography, human rights, postcolonial and subaltern studies, literature, culinary ethnography, and the philosophy of science.