Conditions of Production

Looking at Independent Printmaking Studios in Baroda

Stuti Bhavsar

Published on 10.5.2023

A screenshot of Chandrashekhar Waghmare demonstrating the process of woodcut for Art Katta, 2019.

On seeing Chandrashekhar Waghmare’s[1]prints from his ‘Studio’ series—a woodcut press inside a studio, executed using the medium of woodcut itself—it was the interaction between the printed image and the processes, infrastructure, and tools of trade that lie out-of-frame that piqued my interest. Instead of perceiving wood as simply providing a base for the image, its materiality is foregrounded, making it an active substrate and focusing on the means and conditions amidst which a print is produced. The consideration of the conditions for printmaking becomes evident seeing how Chandrashekhar is the founder-director of Orange Atelier India in Nagpur, which is one of the many printmaking studios run by recent graduates that have emerged in the past decade across India.

During conversations with some of the founders of similar artist-initiated studios in Baroda, the anxieties that graduates carry about the very means to continue practicing printmaking outside the university premises was very palpable. Many of their worries were hinged on its capital-intensive nature vis-à-vis the basic investment in equipment, technical support, and infrastructure that facilitates the processes of printmaking. By focusing on three artist-led, independent printmaking studios in Baroda that have been established over the past seven years—around the same period that Orange Atelier India has existed—this essay examines the conditions of production that underlie printmaking. Centered on Studio Vichitra, Coppar Studio, and Litholekha, this essay attempts to understand their operative models and their spatial, economic, and institutional negotiations, as they evolve into alternate co-learning spaces that are important to the student and artist community of the city.[2]

Historically, it was infrastructural paucity, alongside a need to promote and raise awareness about printmaking and its possibilities, that prompted many artist-led groups and studios to emerge in post-Independence India.[3]Some of these studios include Shilalekh Group established in Mumbai in 1950, Society of Contemporary Artists in Kolkata in 1960, Group 8 in Delhi in 1968, the Realist Group in Kolkata in 1984, Indian Printmakers Guild in 1990, and Chhaap Foundation in Baroda in 1999, among others. Besides providing infrastructure—spatial, technical, intellectual, and exhibitionary[4]—these studios strived to develop their knowledge base through workshops and collaborations to arrive at processes suitable to the Indian market, based on material availability and weather conditions.[5]Whereas heat and humidity are crucial agents that determine how the ink behaves and the image gets etched and exposed, ventilation in the room and its effect on body is also a primary factor, considering the toxicity of chemicals involved. The methods used in the West, from where most of our knowledge base stems, do not always speak to the spatial conditions in India, that vary from region to region.

Today, the motivations behind emergent printmaking studios can be seen as an extension of the earlier needs, along with those posed by the present time, that include and are not limited to: encouraging a specific medium like lithography which was once widely practiced and has become a less preferred medium over time; creating a homely space outside universities that can be helpful to many students, especially considering the lockdowns prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic in the recent past; expanding the scope of printmaking to address and work with digital and newer technologies; maneuvering within the current art market which surrounds printmaking, including NFTs where prints have found a new audience; and rethinking the studios’ organizational models, concerning their registered status as a trust, an NGO, or a company, to help with funding and legalities.

Infrastructurally, it has become easier for a printmaker to own a press today than earlier. Flagging this shift, Subrat Kumar Behera, the founder of Litholekha, explained, “Today it has become commonplace to hear of artists saving up enough through work sales and commissions to buy a press costing around 70-80k. Machines and resources are also being given as awards and gifts—as by Ravi Engineering Works[6]within the Young Printmakers Award and Manorama Young Printmaker Award, or by the company in Baroda to recent graduates who have performed well—creating more opportunities to procure a press compared to next to none earlier.” Moreover, with artists ranging from Jayasimha Chandrashekar in Bangalore and Animesh Maity in Baroda, to Vinay Gosain, a student currently pursuing his Master’s at the Graphics Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (MSU), who are invested in manufacturing machines and tools, things seem to be improving gradually.[7]

Besides the procurement of a press, which is a primary requirement in setting up a facility, another important aspect understood through conversations with the studio founders was that of printmaking being an activity that takes place through collective efforts, be it in terms of labor, technicalities, or handling of processes. Dushyant Patel, the founder of Studio Vichitra, explained how he has often seen studios shut down shortly after starting, or operate intermittently, if the impulse is that of just profiteering or catering to famous artists. He insists, “For printmaking studios in the city to work optimally, it is crucial that multiple people work together, which enlivens the studio atmosphere, motivates people to experiment, and keeps things running.” Dushyant was aided by his time at Lalit Kala Akademi’s Garhi Artist Studio in Delhi and Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal, both open and paid community studios, helping him devise a model for Studio Vichitra.

Jyoti Bhatt (C) and a recent graduate Ramesh Ranavasiya (R) with Dushyant Patel (L) at Studio Vichitra, 2020. Image Courtesy: Dushyant Patel

Dushyant’s long-term experience as the temporary technical assistant within the Graphics Department at MSU equipped him with the know-how of not just various processes of printmaking and its associated technicalities, but also the budgets, needs, and aspirations of students. Secondly, he undertook the production of portfolios with prints by senior artists for Chhaap Foundation, Baroda, in 2015. Although the project remained incomplete, it made him realize how senior artists wanting to produce prints and interested in exploring the medium were unable to get proper assistance, be it physical or technical.

These impulses drove him to establish Studio Vichitra in May 2016 that could cater to three or four artists at a time, run primarily from the returns coming from Dushyant’s own sale of works, consisting of not just prints but also drawings and paintings, which for many printmakers constitutes their main sales. Until 2018, facilities were provided free of cost—except for the final printing paper and plate—but from 2018, the model changed with no fee being charged from the artist in exchange for one print for his collection. Outlining his core objective, Dushyant says, “Instead of focusing solely on artists who have a name in the market, I was intent on creating a space that supports young students and graduates. Vichitra is also open for students who are interested but not necessarily trained in printmaking to intern, build a portfolio, and prepare for their university entrance exams.” During the Covid-19 pandemic, his studio catered to students who couldn’t access university premises, and became an extension of their working space.

When young students work alongside those who have found a footing in the field, co-learning happens at various levels—be it about resolving the issues with prints, finding ways of pushing technical boundaries, and negotiating with the limitations of the material and the image, or the market, the collectors, and galleries—to address issues that seldom get discussed within an art college. Learning also happens the other way around when different generations enter a conversation in myriad ways, with the older generations receiving assistance with new technologies, media, and apps.

The studios under scrutiny in this essay are all located in residential areas, where a considerable part of the artist community resides, and operate out of rented domestic spaces. Upon engagement, these spaces foreground the complex interactions between a workshop space that is industrial and professional in terms of the work process, but homely with regard to the ethos that keeps them afloat. Coppar Studio’s inception, for instance, is hinged more on the latter.

Fazlur Rahman (L) with Chirag Chauhan (R) at Coppar Studio, 2019. Image Courtesy: Animesh Maity

Founded in 2019, Coppar Studio is the brainchild of Charu Sompura, its founder-director, and her partner Animesh Maity, who handles the technical part of the studio. The latter is invested in the analysis, production, and experimentation of tools and materials, that extends the space from simply being a production-based studio to being a center for research. They were introduced to the artist Fazlur Rahman (fondly called Rahman Da), whom they have long looked up to as one of their key mentors, while they were students at Santiniketan and MSU. An important figure—often seen as a studio technician—who seldom receives the acknowledgement he deserves, Rahman Da has worked closely with Rini Dhumal and P.D. Dhumal, among many other senior artists in the city, helping with the production of their prints, apart from having been a long-time employee at the Uttarayan Art Foundation’s printmaking studio in Jaspur. After he was laid off, which was followed by some exploitative experiences he faced with other artists in the city, Charu and Animesh set up Coppar with Rahman Da at the helm. Although the studio was opened a few years after K.G. Subramanyan’s death in 2016, it was at his insistence and in response to his proposition of creating a safe working environment that could cater to the artist community and help students learn from Rahman Da’s expertise and experience, that Coppar was set up.

Priya Bhardwaj (L) and Charu Sompura (R) at Coppar Studio, 2019. Image Courtesy: Animesh Maity

At large, the studio is sustained by Charu’s day job at the Vadodara Visual Arts Centre, which Animesh has also joined recently, easing the financial stress. While the studio doesn’t keep any print for its collection, its users are charged Rs. 1500 a month, which is seen as a contribution toward studio maintenance, basic resources like rollers, inks, and proofing sheets, and the rent of the room. During my visit, Animesh remarked how they intend to instill a sense of responsibility in whoever uses the studio, where everyone contributes to its upkeep while not taking the infrastructure for granted—be it the expertise or the space. The only condition is to abstain from keeping back something without informing others and being sensitive to how that act would pose an inconvenience for a fellow studio-mate, with sharing being the fundamental way the studio can operate with limited resources and a single press.

Animesh’s role of an artist as technician and vice-versa, offers a generative moment to understand mechanical production and how to employ it to create conditions suitable to one’s needs and budget. Research, testing, and experimentation are crucial processes in a technician’s life, since they are supposed to keep up with latest machines and technologies, be able to troubleshoot mechanical, visual, or material problems, and preempt issues to help realize the vision of the artist.

Based on German machines and referencing models manufactured by Takach Press, the studio’s etching press was produced in collaboration with Shivani Enterprise, for their engineering expertise, and sculptor Narayan Biswas, for his structural and artistic understanding in terms of use. Employing his learnings from internships at commercial printing industries and factories such as United Ink, Animesh decided to make PU-based inking rollers that don’t become brittle over time and distribute ink evenly. Moreover, a spur gear with the PU star wheel was added to sync the rotation of the roller and the bed with the movement of the body, so that the eyes move in the same direction as the wheel while taking the print; this causes less inconvenience to the printmaker as opposed to the bed moving in the opposite direction, that Animesh often experienced with presses at MSU.

He is currently in the process of finding an alternative to tusche ink—a wax- and stain-based ink that is expensive and limited in supply—by experimenting with Kanpur ink used for tanning leather. These involvements with materials and machines make it easier for a part to be procured, repaired, or replaced in the future, which is otherwise difficult and expensive. Animesh’s collaboration echoes Boris Arvatov’s formulation on production: “The entrance of the artist into production as an engineer-constructor is significant not only for the organization of everyday life, but for technical development as well.”[8]

Moreover, the above-outlined gestures also make complex the distinction between technicians as culturally kept to the margins and artists who are usually foregrounded. For instance, technicians are hired by studios, artists, and art schools and are required by the senior and well-known artists to help with basic preparation processes like, for instance, filing and cleaning the plates or inking. Additionally, they are often seen undertaking large-scale production of prints once the final print has been approved by the artist. While their involvement has a considerate impact on the final print and image, they are seldom credited or even acknowledged as “creative” practitioners and artists, with their contribution largely being delegated to the body while the artist assumes the role of the mind.[9]

Whereas Studio Vichitra and Coppar have facilities for woodcut, screen printing, and primarily etching, Litholekha is dedicated to bringing lithography into focus. With Litholekha, Subrat Kumar Behera intends to enable conditions to elevate lithography’s relatively minor status in comparison with other mediums like etching that are more popular. Given how there isn’t a dedicated studio to the medium in India, Subrat experienced various challenges in producing lithographs as a student trying to get into MSU’s Master’s program. Secondly, on producing 58 multi-color lithograph panels at MSU’s Graphics Department (where he eventually did his Master’s) for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2016, he found himself constantly negotiating with both the institute and the students. These factors made him initially set up Litholekha as his personal studio. However, after finding it possible to procure 50-60 litho stones—which are slowly becoming obsolete—from old commercial presses and factories in Kolkata and Hyderabad,[10]he opened it to artists and students in 2018. Litholekha’s main objective is to drive the medium forward and create an audience for it—as students, artists, buyers, collectors, and onlookers.

Subrat Kumar Behera (C) giving a demonstration during a workshop at Litholekha, 2019. Image Courtesy: Subrat Kumar Behera

Litholekha invites artists to co-produce folios and holds annual workshops for students across India based on an open call system. The first edition of the workshop had a participation fee of Rs. 2500 which included accommodation and meals, while the material and infrastructural costs were borne by Subrat. With the second edition being sponsored by Ravi Engineering Works, amongst other sponsors, no fee was charged. The month-long workshops were aimed at teaching the technique, alongside addressing the misconceptions around lithography, with organizations like Astanzi[11]being invited for conversations on the medium’s technical, conceptual, and artistic development. These initiatives help introduce lithography not necessarily as an elective subject, or as a compulsory trial module owing to the availability of facilities, but are aimed to equip students with the knowledge and technical base that can enable its pursuit with serious interest.[12]Owing to the current absence of a trained technician and the intensive nature of lithography, which reduces the space, time, and energy that Subrat has for his other projects, Litholekha is selective of the projects and programming it undertakes.

When artists who do not necessarily work with printmaking are invited to co-produce folios, it allows printmaking to go beyond merely being a translation of a painting or drawing into a print for creating multiples. On his recent experience of working with the artists T. Venkanna and Mahesh Baliga, who employed color lithography—a medium that is also very painterly—for the first time, Subrat shared, “It was intriguing to see what they bring to lithography from their process and visual language, and how they make it work for themselves. This in turn becomes a learning exercise for everyone involved, that changes the mediums of lithography and painting, to create a third possibility.”

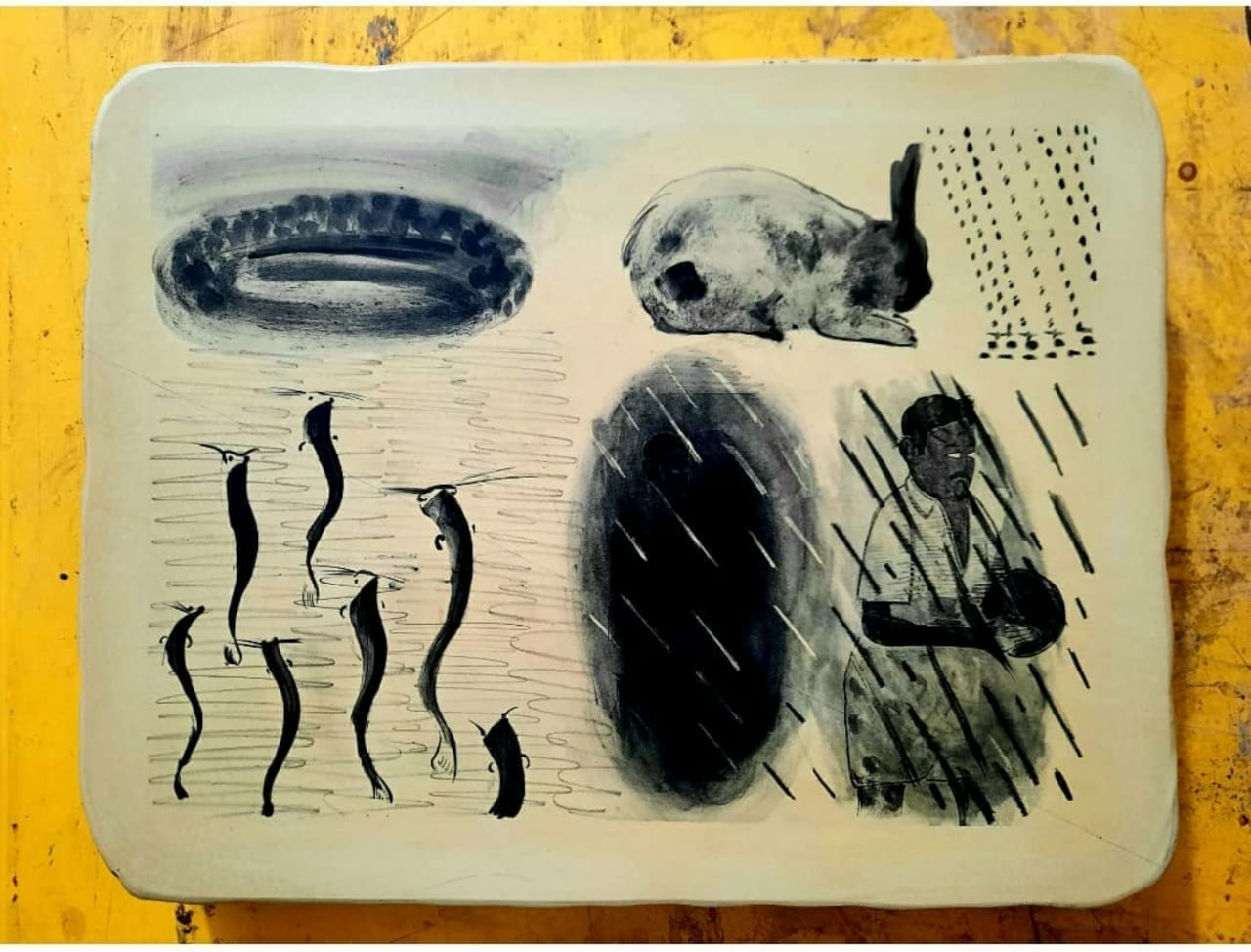

Mahesh Baliga’s practice stone to test and recognize different materials for drawing on a lithography stone, 2021. Image Courtesy: Subrat Kumar Behera

During such collaborations, artists are charged a fee based on their budget and complexity of work toward production that covers studio and material costs. Since Subrat’s own work slows down when such projects are undertaken—proceeds from which would otherwise be used to run the studio—a given amount is accounted as Subrat’s salary/fees owing to his expertise and invested time, with assistants also getting paid for production. Out of the total portfolios co-produced with the artist, one signed portfolio enters the studio’s collection, Litholekha Editions, apart from the artist’s and Subrat’s collections, while the rest are put up for purchase. Litholekha Editions was kickstarted when, on Dushyant’s suggestion, Jyoti Bhatt inaugurated the studio by making a quick drawing on the first stone, which was later co-processed. Litholekha Editions is an ongoing collection that has prints by Vishwa Shroff, Waswo X. Waswo, Walter D’Souza, etc., with whom Subrat has worked, also revealing how a print is still affordable by recent graduates compared to paintings or sculptures by senior artists. Portfolios then become another model through which both Dushyant and Subrat collect, to create an environment conducive enough for prints to be made visible in the market and help sustain new practices.

Dushyant Patel (R) and Jitendra Ojha (extreme L) interacting with students about their practices during Litholekha Workshop, 2019. Image Courtesy: Subrat Kumar Behera

Dushyant’s journey into collecting artist’s works began in 2012, stemming from the boost he experienced on receiving the ‘Best Printmaker Award in Art Summit’ in 2010, which was sponsored by a senior artist. Wanting to continue this model of an artist supporting another and paying it forward, he decided to invest a certain percentage of his earnings toward buying art and supporting another fellow young artist—be it through studio support or purchase of work. He also began collecting works of senior artists that could be liquidated in case a financial emergency arose. Dushyant later started a portfolio with 10 young artists in 2016, which continued for the next two years, for which he neither took any prints nor charged them for using the studio. Instead, 50 editions of each portfolio were produced, and the proceedings from the sales were divided equally amongst all artists involved, including Dushyant.

In closing, it is intriguing to see how the kitchen rack turns into a stand for rollers; the working table becomes a serving table with artists, students, and founders of various studios coming together for a meal, or doubles as a presentation table to know each other’s practices and processes better. Since studios that were largely affected during the pandemic are gradually getting back to normal operations, there’s hope that interactions between these studio spaces will also evolve. The nature of print as an object is changing with the market for prints developing with print triennales, digital platforms, and print-focused shows. It is important for these discussions to take place between the studios and various departments at art schools and universities, to think through various possibilities that can be created for distribution and circulation. Since these studios have been founded in the recent past, the spaces are in the process of building themselves as per their visions to cater to more people and projects. It is only in the time to come, as they maneuver through the situations that they find themselves in, that the conditions for production that they have created and enabled—with its resultant repercussions on the artist community, students, and technicians—will become clearer.

[1] Chandrashekhar Waghmare graduated from the Graphics Department at the Faculty of Fine Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (MSU), in 2013 and founded Orange Atelier India in Nagpur, Maharashtra in 2015.

[2] Apart from the studios outlined above, Mimesis Print Studio run by a group of artists, printmakers, curators, and art historians that opened in 2018, and Awaaz Studio opened by Soghra Khurasani and Shaik Azgharali in the same year, are other important artist-initiated printmaking studios in Baroda to be noted. Both these studios are not just invested in production, but also host a variety of programming, such as studio visits, artist presentations, screenings, lectures, and performances, to locate printmaking amidst a large constellation of methods, disciplines, and artistic exchanges, instead of seeing it in isolation.

[3] Punjab Lalit Kala Akademi. “Paula Sengupta: The Printed Picture: 400 Years of Print Making in India -Punjab Lalit Kala Akademi”, YouTube, 2019. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDrlQqHvnDk.

[4] In the 1970 May-June issue of Vrishchik, is presented a portfolio of contemporary prints with an interview focusing on challenges in printmaking. Vrishchik was a publication edited by Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar, and run out of Baroda. In the interview, Jagmohan Chopra, the founder of Group 8, while sharing his thoughts on the group wanting to expand its activities and take its exhibitions to different art centers in India says, “The group 8 of Delhi organises annual exhibitions of printmaking in which most of the well-known and younger print makers participate… The national or state exhibitions have all these years exhibited prints in a special category, and also given awards to outstanding prints, yet general response of painters, sculptors and laymen to print making was of condescending nature. With more frequent exhibitions of print making, and running of workshops the prevalent misconceptions may change.” Source: https://issuu.com/asiaartarchivehk/docs/gms_vrishchik1970_yr1.7-8/1.

[5] A compilation by Jyoti Bhatt for Lalit Kala Contemporary, No. II, published in April 1970, acted as an information manual, outlining the availability and procurement of print-related materials, machines, and their substitutes—information which otherwise circulates mostly by word-of-mouth. The essay exemplifies how artists worked collectively to ease the difficulty of sourcing materials and used the disseminative potential of the published space to address the basic productional requirements of an artwork. Source: https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/jyoti-bhatt-archive-books-journals-magazines-and-newspapers-featuring-jyoti-bhatt/object/graphic-materials-and-their-availability.

[6] With respect to printmaking presses, Ravi Engineering Works first collaborated with Jyoti Bhatt, who is to be credited with setting up the first etching press in Baroda based on detailed drawings of the machine he had used at Pratt Institute, New York, in 1966. For more information on the centrality of Ravi Engineering Works within Baroda and its collaborations with artists over the years and across disciplines see: Bordewekar, Sandhya. “Machines in the Service of Artists”, Art India Volume XI, Issue I, Quarter I, 2006. Source: https://www.artindiamag.com/wp-content/themes/art-india/archives-files/2006/Vol-11-Issue-1/Vol-11-Issue-1.html.

[7] Except for Jayasimha Chandrashekar, founder of Atelier Prati in Bangalore, who restores old printing presses to a functional condition and also takes up the production of presses for clients, the rest of the artists mentioned have mostly been involved in the production of their personal presses like in Vinay’s case. Animesh initially did intend to manufacture machines based on client requests; however, it is only with time that the plan may be realized.

[8] For a further discussion on artists as engineers and technicians, and vice-versa, see: Arvatov, Boris. “Art and Production”, edited by John Roberts and Alexei Penzin, translated by Shushan Avagyan, Pluto Press, 2017.

[9] Amrita Gupta Singh, in her essay published by TAKE on art in 2010 (Issue 3 - Modern, Vol 1), introduces K.G. Subramanyan’s interview with Jyoti Bhatt, originally published in Lalit Kala Contemporary, Volume 18. In the interview, K.G. Subramanyan addresses another important consideration when it comes to an artist’s approach toward technicalities in printmaking that holds true even today. Although Subramanyan speaks of the artist’s apprehension with regards to photo-mechanical techniques, his addressal is also applicable to non-photographic mechanical and technical aspects in printmaking. K.G. Subramanyan says, “They [the artists] probably thought that the use of complicated mechanical devices will interfere with spontaneity of their statement. They perhaps found the techniques themselves limiting and the technicians they had to work with rigid and unaccommodating. They also perhaps had a sense of status that set technical considerations beneath them. But now the situation has changed… And visual communication activity brings together today a variegated panel of experts, from the designer-artist to the craftsmen-printer.”

Source: https://takeonartmagazine.com/essays/amrita-gupta-singh-on-k-g-subramanyans-interview-withjyoti-bhatt/.

[10] Evil Orientalist. “Subrat Behera in Conversation”, YouTube, 2019. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IsP9Ze9m2EA.

[11] Established and run by Satyajit Dave, an alumnus of the Department of Art History and Aesthetics, MSU, Astanzi was set up in 2017. The organization works as a consultancy firm, dealing with art and antiquities, organizes art appreciation programs and learning modules, and curates exhibitions.

[12] However, with gradually rising numbers of students who are interested in the medium, Subrat is in the process of training them and giving them a stipend, which will enable them to sustain themselves financially and get a space to work and learn at the same time.

* All the online references were last accessed on January 14, 2023.

Stuti Bhavsar is a visual practitioner, writer, and researcher based in Bangalore. You can reach her at stutibhavsar11@gmail.com

Acknowledgment:

I am extremely thankful to Animesh Maity, Dushyant Patel, and Subrat Kumar Behera for their time and patience while sharing their experiences, practices, and processes, and to Digvijay Jadeja and Utpal Prajapati for their help and insights during research.