Camerawork

Delhi

2006–2011

Siddhi Bhandari

Published on 23.9.2025

Photography finds uses across a diverse range of disciplines, from criminology and forensics to anthropology and art history. Critical analysis of photographs can be attributed to the interest shown by practitioners and academics from these disciplines, who regard these images as a visual and material source of data and as an artistic pursuit, offering interpretative and comprehensive possibilities. In social science and humanities, photographs are a source of history and culture and are often used to elucidate and substantiate a theme or period, or as remnants of visual and material culture that underscore their indexical nature. As a practice, it has evolved with time and technology, expanding both the scope of the medium and how it shapes how we see the world.

Aside from the disciplinary focus, the perspective of photographers provides another important lens through which we understand photographs. As practitioners, their approach to photography—as a form of work often articulated as a means of documentation and/or self-expression—offers valuable insights into the individuals involved, their practices, and the social networks that coalesce around the practice, a social system, if you will, that often sustains it. The origin and work of Camerawork Delhi (henceforth CWD), a photography magazine, is illustrative here, but before coming to the magazine, a brief discussion of the term “camera work” is necessary.

“Camera work” is central to the history of photography, and subsequent uses and references to the term can be found in various anglophone publications. For instance, Alfred Stieglitz in America started Camera Work in 1903, a photographic quarterly with a focus on furthering photography as fine art. These were still early days for photography; deliberations on whether this new practice was a mechanical or artistic endeavor were novel and the source of lively debate. Several years later, another publication, Camerawork, a bi-monthly London-based magazine (1976–85), considered to be a radical and “socially conscious”[1] publication, advanced the philosophy of photography, focusing on its politics, documentary and art dimensions, ethics of the practice, and its future.[2] Reflecting on the above-mentioned 1903 publication, Alan Trachtenberg (1978) writes, “Camera Work tended to remove its photo objects from photography itself . . . and placed the object in an order or system of identification known as ‘art.’”[3] These earlier uses of the term “camera work” were restricted to visually pleasing photographs that adhered to certain aesthetic standards but were dissociated from the technicalities of the process and other aspects of photo production.

Christopher Pinney (2010) built on and broadened our understanding of the term in Camerawork as Technical Practice in Colonial India, using it to include the network that forms between the human-machine, and in this instance, translating to the cameraman and the

camera.[4] His aim was to dispel the fixity and pre-determinism that we tend to attribute to photography, and to engage discursively with its fluid and processual nature, even including the social institutions involved in shaping the practice. Borrowing Latour’s dichotomy of the “object-institution,” Pinney stated that photographs do not merely represent what is placed in front of the camera; rather, it is as much created behind the camera by the cameraman who picks up social and cultural cues, often giving a vernacular touch to the photograph.[5] This perspective acknowledges photography as not entirely technologically determined, but as socially created too.

By examining the centrality of social networks in the use of the term “camera work,” I want to explore the existence of CWD, a magazine that questioned the status quo and encouraged newer discursive language and ways of representation through independent photography in India. CWD embodied the philosophy behind its name—camera/network—in the volunteer nature of labor that went into its creation and distribution.

Early networks

Throughout the history of photography, networks of individuals have often imagined and experimented with the medium, allowing it to operate independently of market forces or the need for revenue generation. Since the coming of photography to the subcontinent in the mid-nineteenth century, there emerged initiatives to address the growing need for discussion on the practice for professionals and amateurs alike. Among these were photographic societies and clubs, which were active from the early days of photography and continued to play a role as digital photography became widespread across the country. They are instrumental in catering to the members’ need for knowledge sharing and in building a sense of community. From organizing photo-contests to publishing magazines for their members, these clubs are most active during weekends, meeting for photography walks, tours, workshops, or organizing exhibitions of members’ work; many even offering short-term or weekend certification courses in photography—all done on a volunteer basis. However, their visibility is limited and publicized primarily through word-of-mouth.

CWD aimed to take the conversation around photography beyond what the photo clubs and other networks had to offer in terms of content, methodology, editorial work, and circulation. For one, through its limited series publication, it centered independent photography and critical discourse on the medium. Two, CWD began at a time when photography, along with other forms of communication, was transitioning from analog to digital. The practice was evolving rapidly in a literal sense, creating a need to engage with these changes in a tangible and lasting way. Three, before CWD began, there were no non-commercial platforms for photographers keen to experiment with the medium and to gather and share work and ideas. Many of the photo-journals that focus on contemporary photography—such as Pix andMotherland, or the now-defunct Punctum—came only later.

Beginnings of CWD

Founded by Gauri Gill, Sunil Gupta, and Radhika Singh, Camerawork Delhi was conceived as a space to fill a palpable need for “critical discourse and conversation around independent photography.”[6] Gupta and Gill, both photo-based artists, were introduced to each other through a mutual friend. Trained in photography and educated in the West, they both felt the need for a similar but locally rooted discourse on the medium in India (Gill was enrolled in the Delhi College of Art and Triveni Kala Sangam (where she studied with O. P. Sharma), and later at the New School/Parsons and Stanford University, thereafter; Gupta from West Surrey’s College of Art and Design, later graduating with an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art). The familiarity and participation in the discursive vocabulary around photography that they had both found overseas further pressed them to seek out, or in its absence, introduce similar ideas in the place they were based in—the Indian national capital. Upon first meeting Gupta, and only recently returned from America, Gill found herself speaking to him of the loneliness she felt without her art school peers in the MFA program at Stanford. Towards the end of his MA, from 1983–86, Gupta became involved with the functioning of Camerawork, London. From 1986–88, Gupta was involved with the founding of Autograph in London and later moved on to an advisory role.[7] With the experience of setting up and working in institutions of photography, he told Gill that they could organize in a similar way in Delhi. In contrast, Radhika Singh, with an academic background in social work and sociology, was the founder of Fotomedia, India’s first stock photo agency. This gave her extensive experience working with independent photographers and a deep familiarity with the diversity of their practices. Additionally, Singh’s work involved scouting new talent in photography and organizing exhibitions, which brought her into contact with Gupta when he was sourcing photographic works for an upcoming exhibition in the late 1980s for Autograph, London. Here, Gupta poignantly notes: “One saw only historical India in print, I wanted something from contemporary India.” Singh’s Fotomedia library, which had the work of many independent photographers, became a valuable resource for Gupta at a time when non-commercial, non-family photography was largely confined to non-commissioned or personal work and not readily available to those seeking works by independent photographers outside the mainstream. Through shared work interests and a common social network, the trio developed a working relationship that ultimately led to the founding of CWD.

Published solely in English, the beginnings of the magazine were rooted in the desire to create a platform for independent photographers, writers, lab workers, printers, museums, gallery directors, and other diverse actors engaged in photography to explore what the field meant to them. When pressed on the topic of choosing the name for the publication, Gupta recalled he had the UK-based publication Camerawork in mind as a reference point, while Gill saw the quarterly’s name as their opportunity to “stake claim to the term on behalf of the local community, since the centers of photography as we knew them were all located in the West where they had the power and considered their histories as central.” This is notable as the practice thrived in the subcontinent but had been left out while constructing the medium’s history, aligning with Geoffrey Batchen’s idea of “troublesome field of vernacular photographies . . . for which an appropriate history must now be written.”[8]

Other contributors were Vivek Sahni, a designer who Gill had worked with at India magazine, and volunteered his time and expertise to design and typeset the issues of CWD, and Lucida, an artist collective who took over editorial duties from Gill and Gupta in November 2010.[9]

Beyond the visual: highlights from the issues

Photography as a medium is categorized into different genres that rarely overlap stylistically and professionally. Disregarding these conventions, CWD brought together and platformed a diverse range of these specialties, from journalism to documentary to fashion and art. With a total of eight issues published between 2006 and 2011, it came to be known for featuring independent contemporary photographers. Though its operations were based in Delhi, the magazine’s content reflected a global perspective.

The issues have a marked structure, and despite the wide range of articles, a pattern emerges as one flips through the pages. Each slender issue of about 18 pages, including front and back cover, contained photographs, text supporting photographs, writings on photography, reviews of photographic exhibitions, and interviews with museum directors or those engaged in different aspects of photography. The magazine catered to a wide audience, covering a range of topics from practical considerations to theories of photography. The articles included mostly previously unpublished material contributed by the authors for free. Aside from knowledge sharing, it became a source of information on events related to photography—exhibitions, grants, competitions, and critical reviews of ongoing or concluded exhibitions. While a specific theme cannot be attributed to an issue, one imagines that the editorial decisions and the scope were limited by the variety and timeliness of contributions.

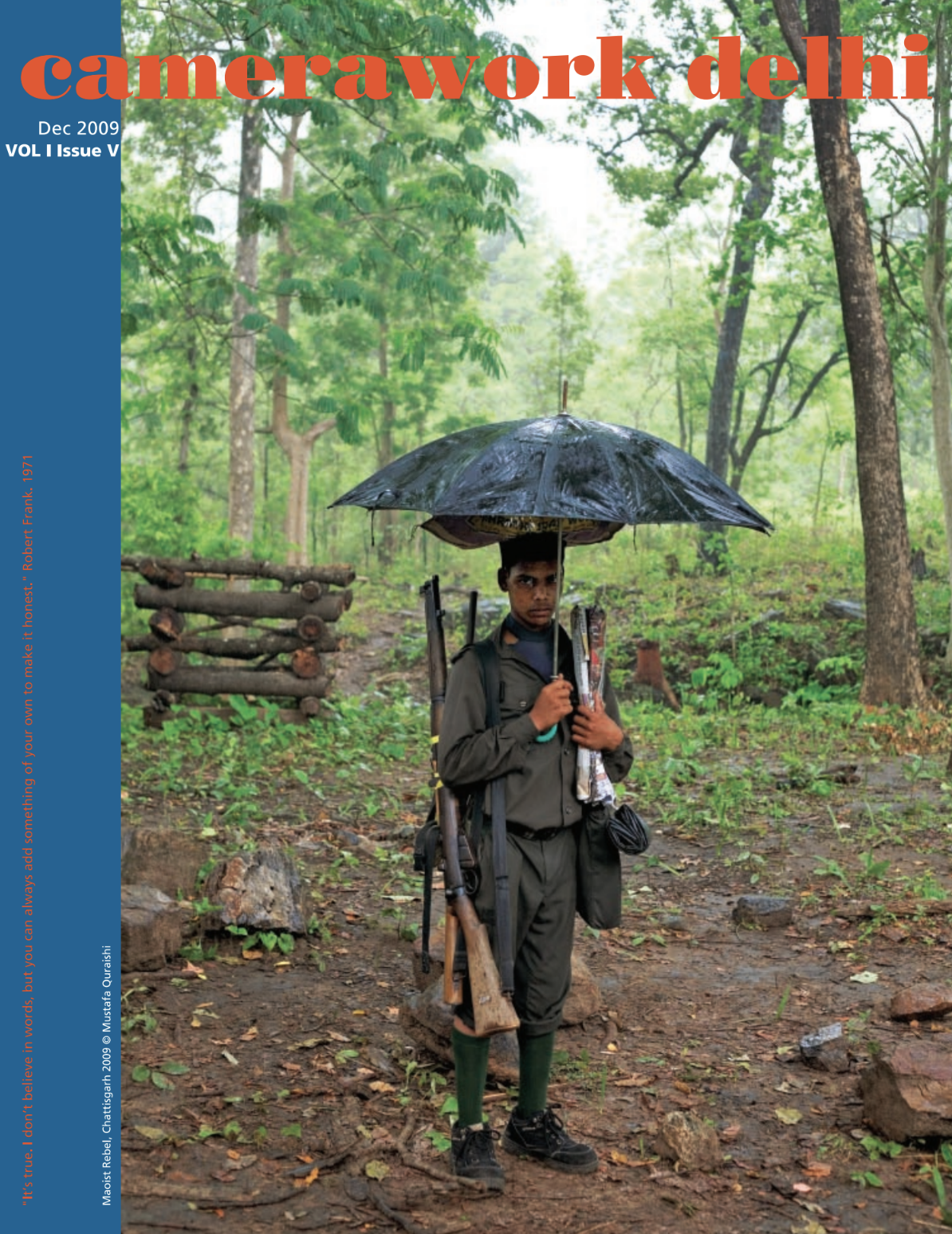

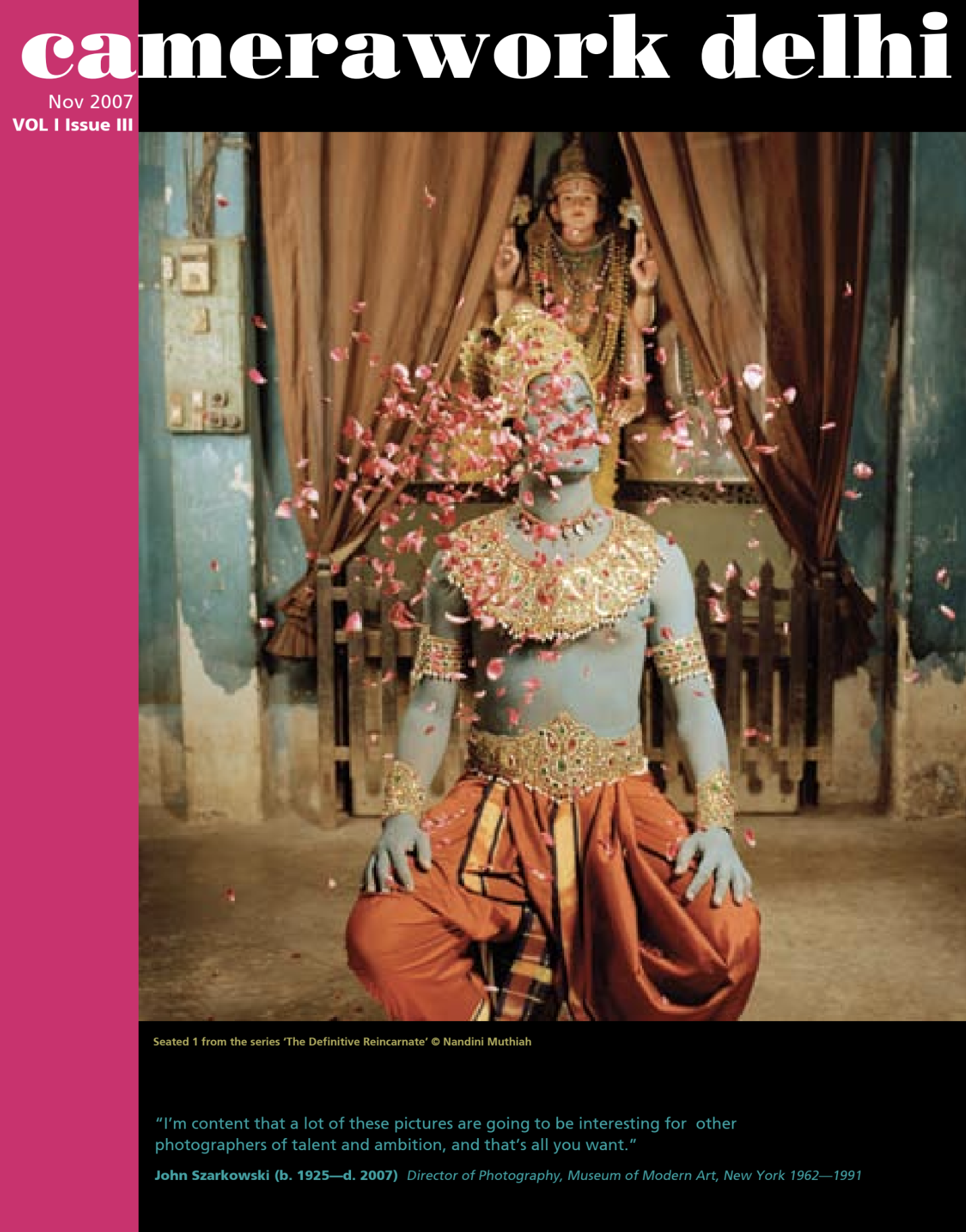

The covers of each CWD issue displayed a full-page photograph and a quote on photography printed along the length of the spine or at the bottom. The pages explored writings on photography that contemplate its diverse dimensions, featuring debates on what makes photography art, social concerns, interviews or conversations with those engaged in different aspects of photography, reviews of exhibitions, and so on. Social issues—like the looming water crisis or industrial pollution in India, or the fight for environmental justice amid toxic pollutants on the highways of California—were featured in photo essays, which were usually long-running projects by independent photographers. There were celebratory announcements of awards and fellowships won by Indian photographers. The back covers featured the details of sponsors, concluded and upcoming events, grants, or any other information and resources related to photography. Notably, the back cover of the very first issue (December 2006) included: “To contribute to March 2007 and future issues, please email suggestions for features and interviews, press information, images and text . . . ” along with the names and email addresses of the three editors. Though this appeared to be an open call for submissions, the editors later revealed that most of the contributions were ultimately commissioned pieces. The names and email IDs of the co-editors continued to be printed on every issue, but the call for contributions was not repeated.

Some of these features included previously published material from international practitioners. These include excerpts from the writings of American contributors, including Allan Sekula,[10] a photographer, writer, and critic, and Robert Adams,[11] which appear in the second and third issues, respectively. CWD also featured retrospectives on the Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy by Hans Verghese Mathews[12],[13] and on Sunil Janah by Ram Rahman,[14],[15] both presented as a two-part series. It also highlighted pioneers of photography in the subcontinent, including a review of India’s first woman photojournalist, Homai Vyaravalla, by Sabeena Gadihoke,[16] as well as explorations of the careers of photographer and printmaker Madan Mahatta[17] and the renowned nineteenth-century photographer Raja Deen Dayal.[18] Additionally, each issue included a portfolio of a contemporary photographer, alongside a standalone photograph given an entire page to “speak” for itself, independent of a caption.

Apart from practitioners, multiple issues also highlighted the role of printing labs and studios; at the time, photography had been primarily disseminated in print as the digital medium was yet to be established as the formidable force it now is. The printing shop proprietors who have been interviewed through the issues include: both from New Delhi, Harry and Laxman of Siddharth Photographix[19] and Ranbir Singh of Digital Image Solutions, a print studio offering “state-of-the-art solutions for your imaging needs.”[20],[21] Similarly, the next issue featured an interview with Vicky of SV Photographic, New Delhi. The questions ranged from how they entered the photography print business to asking for their view on the kind of prints museums collect, the images they developed, and the working relationships with their long-standing customers. Their inclusion also makes it clear that at one point, these printing shops were considered integral to the photographic practice—part of the camera work, so to speak.

CWD and photography education

Gupta was committed to introducing schoolchildren to photography and held workshops at both private and public schools in Delhi. In the second issue, he emphatically makes a case for introducing photography in schools and colleges: “I feel very strongly that for the medium to develop and become enriched to its fullest potential, access to it must be maximized. The most obvious way to do that is via the formal education sector.” Gill was teaching photography full-time at a private school in Delhi through the run of CWD, apart from conducting workshops with rural children in Rajasthan. Echoing Gupta’s viewpoint, she remarked: “Pedagogy is essential to creating any kind of critical discourse around the medium, else it will simply be determined, and ultimately reduced, by the market.” This focus on photography education, particularly through institutional settings, can be directly attributed to both Gill and Gupta’s interest in enhancing the relevance of the photographic medium and fostering vernacular discourse within the pedagogic framework.

By the early 2000s, the institutionalization of photography education was gaining momentum in India, with the establishment of photography programs in colleges and the emergence of new institutions. CWD announced several of these initiatives in their issues. For instance, the third issue reported the launch of an international MA in photography, a collaboration between the University for the Creative Arts at Farnham, UK, and the National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad.[22] The sixth issue featured an introductory write-up by Rishi Singhal on the Apex School of Photography.[23]

In 2009, the fifth issue featured an interview with Dr. Deepak John Matthew, who was instrumental in establishing the two-year postgraduate diploma course in photography at the National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad. The program was regarded as “pioneering,” addressing a long-standing gap in India’s art education—“a course that recognizes photography as a medium of artistic expression and delves deeper into academic inquiry was completely lacking in the country.”[24] Both Gill and Gupta have taught at this program as serving on juries evaluating student work.

Navigating monetary considerations

The publication of CWD relied on a network of people at many levels. As mentioned previously, most of the contributors had to agree to provide their previously unpublished works without an honorarium. Vivek Sahni designed the magazine for free, and the volunteer nature of his work also included print production work, such as color correction of the images, typesetting the final layout, and overseeing the print process at the press. Apart from their editorial responsibilities, the three founders also contributed to the content in the form of interviews and reviews of shows.

Additionally, institutions such as Khoj, the French Embassy in India, Alliance Francaise de Delhi, and Pro Helvetia would sponsor the publication of individual issues. Events such as film screenings, discussions on emerging practices, and fundraising were organized around the launch of each issue of the magazine, with Gill noting, “Occasionally when the issues came out, a non-profit like the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA)’s Reading Room covered the cost for a community event where we could gather to distribute copies, have chai, and show projections of work by photographers.”

Once, portfolio reviews were held in the four major metropolitan cities, attracting over 600 submissions. Participants were assigned time slots, and organizers volunteered to provide feedback on their work. The process was novel for the time and, though on a small scale, helped spread awareness of new ideas and practices in photography. More importantly, it fostered a sense of community, offering emerging artists and photographers a platform for critique and, in some cases, an opportunity to have their work recognized.

Initially, the print run was limited to 500 copies, which increased to 1000 when provided with organizational support. According to Gupta, they specifically chose to display the copies in selected places frequented by young people, such as bars, coffee shops, bookshops, etc. Gill would drive around the city dropping off issues, often enlisting fellow photographers to help. The initial issues were free; however, later issues were made available at a nominal price of 50 rupees. The editors of CWD experimented with the magazine design, enlarging the size from A4 to A3, but the larger format proved too unwieldy for distribution and soon reverted to the original size. The publication was intermittent as it was contingent on funds and volunteer availability. There were no advertisements, even from interested photo labs, as the editors believed this would constitute a conflict of interest. There was a discussion on whether the issues should be available online, but was ultimately vetoed because it could be considered as exclusionary in a country like India, where access to the internet was limited at the time. Moreover, photography was largely perceived as a print medium with all the associations of an emphatic materiality.

During the years that CWD was in publication, analog and print photography were prevalent. It created its own niche at a crucial juncture when photography was changing rapidly, and many of those changes were ushered and recorded in the pages of this magazine. During its print run, it was an exalted acknowledgment to be published in CWD amongst established or up-and-coming photographers. Eventually, the publishing of CWD became unsustainable due to a lack of funds, overall support, and other resources needed for an organization of this nature. Gupta noted that “. . . abroad, a university would take you in, but in India, it wasn’t the case because photography was not yet as popular in institutional settings.”

The art world, network, and camera work

There is an identifiable social network and the labor of different actors that go into the creation of a magazine like CWD. When reflecting on its collective nature, I return to Becker (1982) and his notion of art-worlds to denote “the network of people whose cooperative activity, organized via their joint knowledge of conventional means of doing things, produces the kind of art works that the art world is noted for.”[25] He further states that “All artistic work, like all human activity, involves the joint activity of a number, often a large number, of people . . . The work always shows signs of that cooperation.”[26]

To extend this argument in the case of CWD, we see that collaboration begins right from the identification of need, the conception of ideas, solicitation and contribution of content, editing, designing, printing, and distribution. These labors are important, in varying degrees, to see a publication through. The collaboration transcends Arendt’s division of vita activa (life of action) into labor, work, and action, and shows signs of all in the process of production.[27] The labors further go on to include vita contempletiva, i.e., a life of contemplation, as the process of creation is multi-layered and demands different labors at different stages.[28] The editors deliberate on and share their ideas on the works that can be included in an issue, the contributors produce that work, which takes various forms. Then there is the design, printing, and distribution, which requires mental and physical labor. All of this also attributes a hierarchy amongst the collaborators and their participation in the production process. Some are engaged in the core activity—the contributors, the deliberators, and designers; others contribute at the periphery—printers, distributors. But it is only when it all comes together that the object—the magazine in this case—comes to life. My analysis of CWD approaches it like a historical object, an artefact if you will, and explores the meaning it conveys in the present.

CWD was an independent publication, refusing advertisements or entanglements that could potentially curtail their freedom. Interestingly, though CWD centered the photographer, it emphatically highlighted the associated labor that went into its production. In my exchanges with two of the co-founders, their narration was focused as much on the cooperation between the different actors that led to the creation of CWD, issue after issue, as it was on its content. Though the first issue of CWD seemed to actively solicit contributions, it would go on to mostly publish commissioned pieces, mainly from the founders’ social networks of young and upcoming or more established photographers. There also emerged a certain familiarity between people and their work that preceded the creation of CWD. It is these networks of voluntary contributions that sustained the magazine and helped it stay independent of the demands of the market. These networks are fluid, as people join or move away to become part of other similar ventures and continue to contribute their expertise and labor.

CWD furthered the discourse around the practice as they championed the proliferation of photo festivals or publications with a focus on independent photography. The last CWD publication was in 2011, and although understated, it served to present, publicize, and ultimately chronicle initiatives that would go on to shape the independent photography scene in India as we know it today. For instance, the eighth issue (November 2011) carried the post-event announcement of the just-concluded first edition of Nazar Foundation’s Delhi Photo Festival. Described as “India’s first international photography festival,” it featured over seventy photographic shows and featured the work of independent photographers from twenty-five countries. Though CWD would cease publication shortly thereafter, it nevertheless contributed to the broader social network that fostered the emergence of platforms such as the aforementioned Delhi Photo Festival,Chennai Photo Biennale, PIX magazine, and Indian Photo Festival.

In my conversations with Gupta and Gill, it was heartening to hear them generously credit each other for helping CWD become what it set out to be during its years in print and circulation.[29] There is something realistic, yet poignant, about the decision to stop, and for CWD, Gill noted that the decision to halt publication came organically. With Gupta’s return to the UK, the efforts required to solicit and edit submissions, raise funds for printing, and distribute copies became a pressing and inescapable concern.

I began this essay by describing the use of photography by different disciplines, but there is an emphatic shift that happens when photography itself becomes a discipline, finding an increasing number of those keen to learn the art and craft. My conversation with Gupta, now primarily an educator, reiterated that teaching photography within an institutional setting is still fraught with challenges: “We won’t have an Indian discourse till we have more schools teaching photography.” Institutionalized photography spaces are shrinking, and one cannot help but feel that a platform like CWD is needed to deliberate on our increasingly visual world, generated by humans and artificial intelligence alike. We are in a post-photography era with an inundation in the production, circulation, and consumption of visual material, and it makes one question the nature and scope of photography as a medium of representation. However, Gill’s email communication ends on an optimistic note: “We might revive it someday, who knows. Or it will have disappeared like one of the many bubbles that arise and disintegrate, but not without creating some ripples.”

[1] The term was used by Sunil Gupta over a telephone conversation when talking about Camerawork London. However, this becomes evident as one flips through digitized and archived issues of the magazine.

[2] “A Brief History of the Publication: Camerawork Magazine,” Four Corners Archive, accessed June 6, 2025, https://www.fourcornersarchive.org/archive/index?theme=54.

[3] Alan Trachtenberg. “Camera Work: Notes Towards an Investigation,” The Massachusetts Review 19, no. 4 (1978): 837.

[4] Christopher Pinney, “Camerawork as Technical Practice in Colonial India,” in Material Powers: Cultural Studies, History and the Material Turn, eds. Tony Bennett and Patrick Joyce (London: Routledge, 2010), 145–68.

[5] Ibid, 148–49.

[6] Gauri Gill, Facebook post, November 18, 2022.

[7] Autograph, established in 1988, is a gallery in London with the “mission [to] champion the work of artists who use photography and film to highlight questions of race, representation, human rights and social justice.” “Our Mission”, Autograph, accessed July 5, 2025, https://autograph.org.uk/about-us/mission

[8] Geoffrey Batchen, “Vernacular Photographies,” in Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 57.

[9] Lucida was a visual artists’ collective. They aimed to influence visual thinking via a design-oriented approach in moving and still image-making services. In 2010, the collective was started by Suruchi Dumpawar, Mridul Batra, Arunima Singh, and Pradeep Menon, all graduates of the first few batches of the diploma program in photography at the National Institute of Design (NID) where they studied under Gupta. The collective came to a conclusion after a few years.

[10] Allan Sekula, “On the Invention of the Photographic Meaning,” in Thinking Photography, ed. Victor Burgin (London: Macmillan, 1982), 84–109.

[11] Robert Adams, Why People Photograph: Selected Essays and Reviews (New York: Aperture, 1994).

[12] Hans Varghese Mathews, “The Photogrammata of Lazlo Moholy-Nagy,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 5 (December 2009): 13–14.

[13] Mathews, “The Photogrammata of Lazlo Moholy-Nagy (part 2),” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 6 (April 2009): 13.

[14] Ram Rahman, “Suni Janah: A World in Black and White (part 1),” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 6 (April 2009): 10–11.

[15] Rahman, “Suni Janah: A World in Black and White (part 2),” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 7 (November 2010): 11–12.

[16] Sabeena Gadihoke, “Homai Vyarawalla - A Curator’s Perspective,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 7 (November 2010): 15.

[17] Madan Mehta, “Madan Mahatta on his Photographic Journey,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 3 (November 2007): 9–10.

[18] Satish Sharma, “Photographing India: Journeys with Raja Deen Dayal and Henri Cartier-Bresson,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 1 (December 2006).

[19] Harry and Laxman, “An Interview of Harry & Laxman of Siddharth Photographix Bhogal, New Delhi,” interview by Gauri Gill, Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 2 (May 2007).

[20] Ranbir Singh, “An Interview with Ranbir Singh,” interview by Gauri Gill, Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 3 (November 2007): 7.

[21] “Studio,” Digital Image Solutions, accessed June 7, 2025, http://www.digitalimagesolutions.in/studio.html.

[22] Anna Fox. “Education: International MA in Photography,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 3 (November 2007): 16. The course initially offered at NID was a Post Graduate Diploma Programme (PGDP) in Photography Design, which was later restructured into a Bachelor of Design (B.Des) degree. Both institutes collaborated to offer dual degrees to photography students. The University for the Creative Arts offered an MFA as a dual degree.

[23] Rishi Singhal, “Apex School of Photography,” Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 6 (April 2010): 15.

[24] Deepak John Matthew, “In Conversation with Deepak John Matthew,” interview with Mridul Batra, Camerawork Delhi 1, no. 5 (December 2009): 15.

[25]Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), x.

[26] Ibid, 1.

[27] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 7.

[28] Ibid, 14.

[29] The author attempted to contact Radhika Singh over email, but was unsuccessful.

Siddhi Bhandari is Faculty, Srishti-Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru, India. Her research and teaching interests include research methods in the social sciences, material culture, visual culture and oral history. She holds a PhD from the University of Delhi, where she worked on the sociology of photography for a thesis titled ‘Photographers and Photography: A Sociological Study’.

Access the entire Camerawork Archive, here.

The archive is accessible courtesy of the editors of the magazine.

The archive is accessible courtesy of the editors of the magazine.