Beyond the Social Turn

The Dialogue Interactive

Artists Association (DIAA)

Arushi Vats

Published on 10.07.23

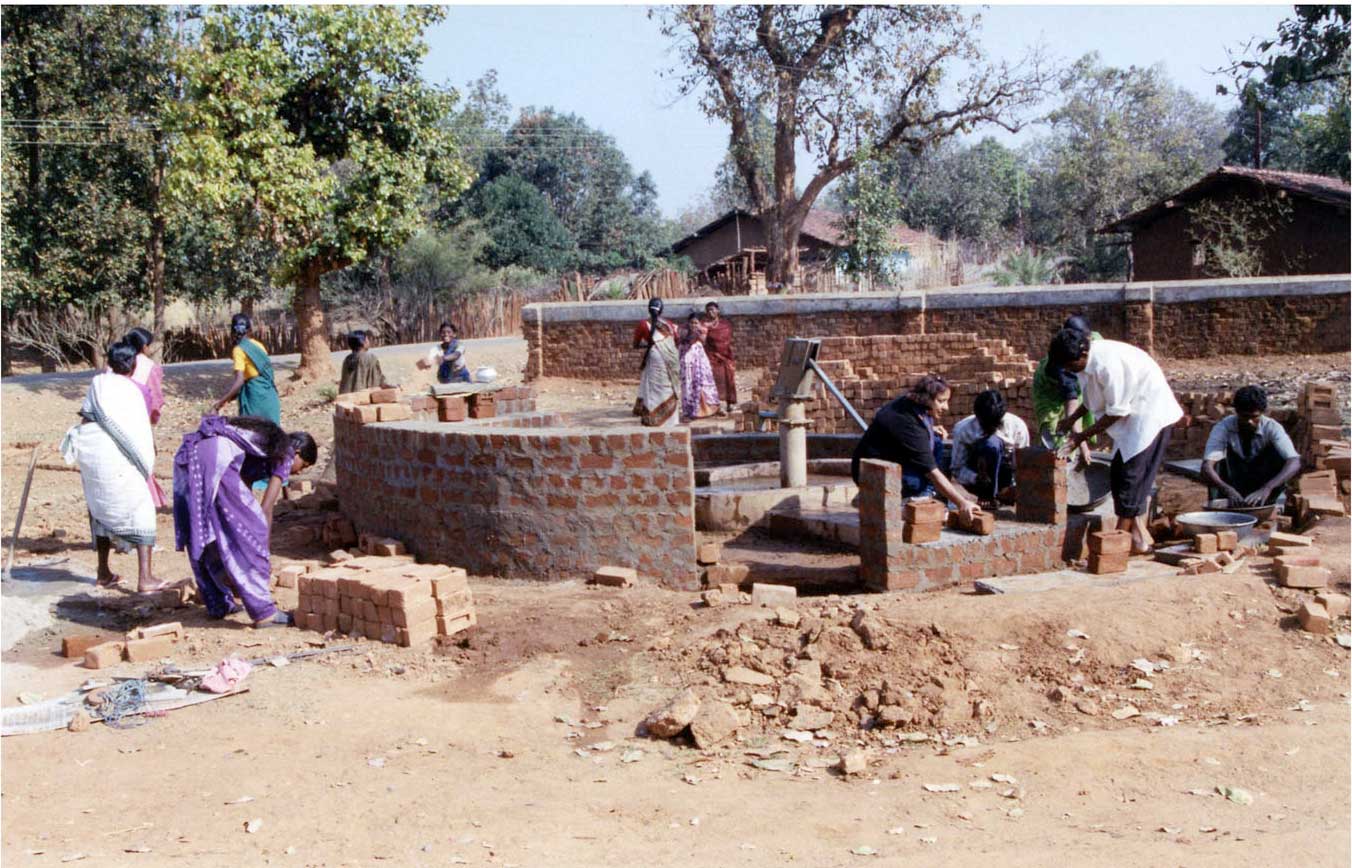

Navjot Altaf, Rajkumar Korram, Shantibai and Gessuram Viswakarma, Nalpar (Water Pump Site) Kopaveda, Kondagaon, Bastar, Chhattisgarh, India (2004), Photo: Navjot Altaf

Situated across the sun-struck earth of Bastar, in the villages of Kondagaon district, are concrete structures rising from the ground—vertical, gray, and geometric. Some are developed as concrete screens that are filigreed with sharp, utilitarian symbols, another is designed as a sundial, and yet others as tubular forms of varying curvilinear density—evoking water sources and the ways of its storage, movement, and circulation. At the center of each is a water pump—a common source of water in the villages of Bastar, which lack running water supply in the interior regions. As of the time of writing this, there are six Nalpar or redesigned community water sites in the Bastar region, a project conceptualized and co-developed by an artist organization and members of the local community.[1] Rising as visually powerful forms in the landscape, to some viewers, they may be reminiscent of the utopic brutalism that marked the advent of socialist modernism. Yet, for the artist organization and members of the community that created these structures, the symbols evoke patterns intimate to the Adivasi community, including the circular form of the water sites, which signifies transformation in the indigenous culture of the region, among others. The aesthetic is compounded by functional and social concerns—the water pumps are most frequented by women in the village. The concrete screen which envelops the pump provides them respite from the constant surveillance of their bodies by male members of the community and encourages acts of gathering; there are shelves and curved indents which punctuate and ease the gesture of lifting pots filled with water, and there is a drain that routes the runaway water to a small tank for reuse, preventing it from stagnating.[2] The project was developed in dialogue with residents and municipal officials, with redesigns and alterations made based on the insights emergent from such exchanges. From the design and the symbols to the construction of the pumps, the project grew as a way to not only fill the material gaps in public works but to also shift unarticulated yet embodied social systems of control that are often missed in outlays of local governance.

In 2006, when Claire Bishop wrote The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents—an essay which now lurks as Hegel’s ghost over any discussion on art and collaboration—her contention was with proponents of socially engaged art who were shifting the focus away from the compositionally stable form that art assumed for viewership, to the more amorphous, ephemeral, and opaque terrain of processual deliberations and dialogues that preceded its material fixity. Bishop was alarmed by this turn to collaboration as she felt it signaled a de-valuing of aesthetic concerns, and a propensity toward what she identified as ‘authorial renunciation’ but implied as an ascetic infallibility of the socially engaged artist, in the pale of which any conceptual discussion of a work would always be bookended by the noble intentions of its makers.[3]

To Bishop, these qualities make socially engaged art critique-resistant if not critique-proof, leaving the art critic in a state of haplessness. Describing the facets of socially engaged art, Bishop notes: “Dynamic and sustained relationships provide their markers of success, not aesthetic considerations.”[4] Relational aesthetics, Bishop notes, is enticing; but how to adjudicate its success and failure as art?

It takes little effort to recognize that the categorical binaries which appear in Bishop’s essay are at best reductionist, and far more damagingly, false. In the essay, the aesthete and the activist, the ethical and the conceptual, the concentrated spectacle and the protracted quasi-governmental forms that ‘political’ art assumes, and truth and fabulation (‘artifice’) are presented as irreconcilable states. Another polarity which underpins Bishop’s analysis is the idea that artmaking precedes the made form, a linear consciousness which limits both art and critical considerations to a ‘final state’. Yet, socially engaged art, which implies a plurality of authorship and occurs in the midst of life, identity, beliefs, institutions, infrastructures, resources, and aspirations, is rarely if ever ‘fixed’, and, quite often, is simultaneously emergent from and posited against the material and communicative conditions of its field. Such entangled and fluid states of becoming do not necessarily preclude socially engaged art from critical appraisal, but rather shift the grounds of criticism, which must now trace and address multilateral movements, plural cadences, and the variegated textures of human encounters—ranging from friendship, accordance, and alliance to antagonism, indifference, and incompatibility.

People Fetching Water, Kondagaon Naka Structure, 2001.

People Fetching Water, Kondagaon Naka Structure, 2001.Consider the formation of the Dialogue Interactive Artists Association (DIAA) in Kopaweda, which emerged from the conversations and experiences of four artists working together at Shilpi Gram in Bastar. In 1996, Shantibai, Gessuram Viswakarma, Rajkumar Korram, and Navjot Altaf met at Shilpi Gram—an independent institution established in 1981 by sculptor Jaidev Baghel, a member of the Adivasi community, with the intent to foster engagement between local and visiting artists and to promote Adivasi artistic voices. During the years 1996–1997, the group, including art historian Bhanu Padamsee participating as an observer, developed a proposal for a grant by India Foundation for the Arts. They aimed to explore the possibilities of communication between artists from varied socioeconomic backgrounds and to disprove persisting misbeliefs about Adivasi art forms. The grant enabled the group, which further included artists Raituram and Kabiram, as well as Navjot’s studio assistant S. Raju Mewada from Mumbai, to spend time traveling in Bastar to the villages of Matnar Gudi and Tongpal, among others, to see the art and architecture of the region, while also working on wooden sculptures.[5] This series of sculptural works made by all the participating artists during the project titled Modes of Parallel Practice: Ways of World Making (1997–1998) was displayed at the first Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale (1999) in Japan. They were acquired by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, thus providing the group with the funds which would later be utilized to set up the DIAA.

While at Shilpi Gram, they were invited by high-school teachers to conduct art workshops for children, which resulted in the development of Chawal ki Kahani (1997), an installation and performance suggested and led by students over a period of four months and culminating in a performance program at Shilpi Gram. The topic of drought, which was sweeping the region that year, was topical and pertinent to the lives of the children. Bastar, traditionally known as the ‘rice bowl of India’ with over 20,000 varieties of rice—denoting a vivid agro-diversity in the region—has faced not only conditions such as drought but also the onslaught of market forces propelling the cultivation of more commercially feasible varieties of rice in a drive toward monoculture. With the liberalization of India’s economy in 1991 and the encroachment of private markets on various spheres of life and the gradual abeyance of welfare schemes, the emergence of the DIAA and its initiatives, which have focused on community sites and community-centric concerns, was an urgent and necessary intervention.

Writings on art and social action are marked by a form of hierarchy that scholar Nancy Adajania describes as ‘residual paternalism’ innate in the notion of the artist as the initiator of social change, retaining the ‘asymmetry of cultural, social and political capital’ between the artist and the field.[6] When Modes of Parallel Practice: Ways of World Making was displayed at the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale, the display was initially credited to Navjot. Upon her request, it was amended to list each contributing artist’s name. Navjot was keen to imagine other formats of engagement, which Adajania terms as a principle of devolution—‘devolution of artistic privilege’ and the shedding of any ‘claims to expertise that reside with her under an inequitable system’. This devolution enables the artist to collaborate in an “as yet unmapped space of practice” where the idea of “equality is constantly tested, redefined and reformulated in the act”.[7]

Nalpar, Handpump site, work in progress, in the image Botiram and women artists from IFAD, Sambalpur, Bastar, 2000.

Nalpar, Handpump site, work in progress, in the image Botiram and women artists from IFAD, Sambalpur, Bastar, 2000. The experience of running a workshop with students in Kondagaon and outside Bastar led to the formation of the ‘collectively initiated’ organization, which was later formally named the DIAA. Navjot, Shantibai, Rajkumar, Gessuram, and Gangadevi were joined by six other local women artists as key steerers, with whom Navjot had been working on site-oriented projects and bell-metal sculpture workshops supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development. DIAA’s projects have involved various participants, ranging from residents to municipal officers, lawyers, writers, farmers, artists, and academics, notably scholars Nancy Adajania and Grant Kester, who both participated in iterations of Samvad, a seminar format which has included performances by theater groups such as Mirror Theatre from Odisha, playing to local audiences numbering up to four hundred. The repertoire of the DIAA is not dissimilar to what Bishop labels as the ‘predictable formula’ of workshops, pedagogy, exhibitions, and design and construction of public facilities—all rooted in the ground of Bastar. Geeta Kapur notes that this ground is the “everyday space where bodies move and perform and survive… determined by social norms.”[8]For Zitzewitz, these projects “… involved the violating of the categorical distinction between art and life—a border-crossing that had serious consequences for the lives of the participants.”[9]

Such consequences included Jaidev Baghel’s assessment that while the structures which emerged as the result of the artists working with other residents of Bastar were powerful, the immaterial processes of workshopping, conversations, and dialogues with Bastar residents that preceded it did not suit Shilpi Gram’s commitment to producing and promoting Adivasi art. In a dialogue with Kester, Navjot commented on Baghel’s distinction of the two—“Jaidev recognizes Nalpar structures as artworks but not the process.”[10] Interestingly, such sharp distinctions between the act of making, the made form, and its lifecycle of usage by numerous persons did not inhibit the imagination of the artists. Relocation from Shilpi Gram propelled the collective to build a structure from which they could work, and to formalize the DIAA as an association that would engage in a critical and site-led praxis, as opposed to creating individual works of art.

Navjot, who had been exploring the female form and women’s writing in a series of works and was aware of gender as a blind spot in revolutionary Marxism, was keen to work with Shantibai. Married to a sculptor, Shantibai’s gendered location restricted her artistic work to the painting of sculptures made by her partner. In the DIAA’s engagement with residents of Kopaweda, there is a nuanced understanding of subjectivity as intersectional and complex—its two spatial projects, public water-taps redesigned and restructured for expanded usage called Nalpar, and play and pedagogic structures for children called Pilla Gudi, address gender and adolescence as vectors of social location that need infrastructures of support. Karin Zitzewitz describes the DIAA’s projects as “movement beyond critique to make modest but meaningful improvements upon existing infrastructure,” with the idea of infrastructural systems conceived as determining the very “distribution of life” in a site.[11]

The DIAA’s projects strike the issue at the heart of Bishop’s essay—is this art or something else? Scholars such as Zitzewitz, Adajania, and Kester who have written on the DIAA are aware that its interventions may be mistaken as merely public works programs, not unlike those run by developmental agencies. Adajania argues that the pumps are not a “piece of developmental architecture” but that they encourage “new social behaviors, new attitudes, and ultimately a new sense of dignity.”[12] For Karin Zitzewitz, “it is a properly artistic act to rethink the pump with the needs of the women and children who use it at the forefront (…). It understands the tap as a cause of an array of social effects, and therefore a useful site for intervention.”[13]

The impulse in the DIAA’s projects toward stylization, motif, and architectural elements troubles Bishop’s dismissal of socially engaged art as not invested in questions of form and composition or matters of aesthetic consideration. In the Pilla Gudi (‘temples for children’) project, for instance, the locations for the structures were suggested by residents of the villages. The need for a space where the youth of the village could interact outside of rituals or religious congregations, in the form of play, workshops, oral narrations, or any use they deem fit was realized in conversations with students. Kester notes that in the first Pilla Gudi (2001) at Kusma, Rajkumar consciously chose to design the structure in reference to a famous Adivasi ‘Mother Goddess’ temple at Matnar, which has a ceiling with carved figures of deities gazing upon those standing beneath. In the collective’s design for Pilla Gudi, however, the ceiling was inlaid with mirrors, to reflect children’s own images to them, a subtle suggestion of holding their own ground and moral worth.[14] Adajania writes in The Thirteenth Place that in Kopaweda, children were invited to make design sketches for the structure and the Pilla Gudi was designed based on a sketch by then nine-year-old Somnath. For Kester, Pilla Gudistructures and sites also hark to the institution of ghotul, a dormitory-like hut used by adolescents and young adults in Adivasi communities—especially in the Gond community—to play, share time, and exchange ideas, which is also managed by them and even described as ‘children’s republic’. The expansion of religious fundamentalism in India has also touched Bastar, where indigenous institutions such as ghotul have faced censure for permitting children of various genders to spend time together and have been under duress from the local government. The construction of Pilla Gudi across Bastar is an effort to retain a tradition intrinsic to the ethos of the communities of the region and in marking space for unfettered exchange and cross-generational sharing as conditions for the emergence of a ‘politics of knowledge’ beyond formal school curriculums, which are lacking references to the contexts and communities to which students in the region belong. It becomes possible then to reframe the earlier question drawn from Bishop’s essay to: What modes of criticism does such art necessitate and engender?

Once art is removed from a sanitized, controlled environment such as a gallery or a museum, the critic’s relationship with the work-in-the-world also changes. Kester describes this shift by noting that in such projects “meaning is produced through gradual accretion” and the critic must “spend some time with the artist, ideally in the site of the actual project, talking to other participants and trying to gain a sense of its gestalt.” Additionally, the critic now has to develop “language or terminology that can capture this shift in a compelling manner.”[15] The DIAA’s efforts to develop such vocabularies—primarily through seminar programs as part of Samvad that function as cross-disciplinary fora, inviting local and visiting writers, poets, journalists, critics, theater groups, activists, and thinkers to engage with questions collectively and following no fixed format—is a vital pivot to understanding that discursive and material thought are deeply entwined in the practices of its members. While many utterances, interpersonal frequencies of exchange, and facets of personal understanding have been traditionally understood to be outside the purview of the archive, it is important to recall Bastar’s strong traditions of oral history and Navjot’s philosophical engagement with women’s writing—a practice which has historically flourished in the form of notebooks, personal journals, and memoirs that are attuned to the cadences of daily life. Learning from these longstanding acts of crafting, narrating, and recording life beyond the conventional imaginations of the document, and which represent modes of remembering that have existed outside the orbit of institutions, members of the DIAA are equipped to appreciate and draw critical insights from the fluid nature of their practice.

Having fun?, workshop at Pillagudi, Kopaweda, Bastar, 2013.

Having fun?, workshop at Pillagudi, Kopaweda, Bastar, 2013. The term offered as an alternative to the smoothened, professionalized modularity that stains ‘collaboration’ and enables its acquiescence in the art market, is ‘cooperative art’, as proposed by Navjot in an essay—which I read as art with real stakes, with members of the collective sharing funds, sharing responsibilities for projects, and upholding the self-sustenance of the association. Unlike ‘collaborative art’, which seeks to erase creases and ruptures toward an artistic outcome, Navjot describes the approach of the DIAA artists as one which sought not “coherence, but difference” with a mode of engagement that does not “lead one to abandon independent thinking.” Initiatives such as Samvad, which foster acts of reflection and thinking together, ensure there is an auto-criticality embedded in the process.

Navjot has noted that working with many persons, with varying perspectives and social locations, “is a complex process and at times it causes friction.”[16] In each of the projects, there is the creation of new communication networks, as persons are brought into contact and to places of discursive exchange. Projects are often led by different members of the collective, and involve different actors—schoolchildren, women, the elderly, or administrative officers. To the degree that it asks of every person involved their presence, consideration, suggestions, and the generative act of speaking their mind, the projects are participatory without being transactional. Adajania shares the term ‘baithiya’ proposed by Rajkumar, which comes from the local dialect, as a mode of helping out with day-to-day needs with the principle of mutual aid, devoid of any transactional gains, competition for resources, or the whiff of bureaucracy.[17]

I would argue that many of the material aspects of a project, whether in the form of a structure or intervention, are also not a point of fixity but are phenomenologically unbound. In their use by a public, these structures enable trajectories of association which cannot be mapped. The DIAA beckons a similar openness to the act of criticism, which must consider whether bracketing or delimiting the frame of study in the pursuit of conceptual wholeness may reduce the prismatic nature of many artistic endeavors. The DIAA’s projects thus signal a shift in the question being raised by Bishop in The Social Turn, moving it away from categorical concerns of ‘art or art enough’ toward asking: What may be discovered by criticism if it were to embrace the fragmented, multifocal, intersectional, and dynamic positions that comprise a social duration?

[1] Grant Kester, ‘Samvad in Kondagaon: Navjot Altaf and Collaborative Praxis in an Adivasi Village’ in Navjot at Work (Mumbai: The Guild Art Gallery, 2022), 191.

[2] Elena Bernardini in Navjot at Work (Mumbai: The Guild Art Gallery, 2022), 94.

[3] Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’, Artforum, February 2006.

[4] Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’, Artforum, February 2006.

[5] India Foundation for the Arts, Grantees: Navjot Altaf, http://indiaifa.org/navjot-altaf.html.

[6] Nancy Adajania, The Thirteenth Place: Positionality as Critique in the Art of Navjot Altaf (Mumbai: The Guild Art Gallery, 2016), 195.

[7] Nancy Adajania, The Thirteenth Place, 195.

[8] Geeta Kapur, Foreword in Navjot at Work (Mumbai: The Guild Art Gallery, 2022).

[9] Karin Zitzewitz, ‘When Does Infrastructure “Qualify for [Artistic] Attention”? The “ABCs” of Contemporary Art in Post-Liberalization India’, Journal of Material Culture, 27:1, March 2022, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/13591835211069613, 41.

[10] Navjot Altaf in conversation with Grant Kester, available on Dialogue Samvad, https://www.dialoguebastar.com/correspondence-between-grant-kester-and-navjot-2008.html.

[11] Karin Zitzewitz, ‘When Does Infrastructure “Qualify for [Artistic] Attention”?’, 33.

[12] Nancy Adajania, The Thirteenth Place, 245.

[13] Karin Zitzewitz, ‘When Does Infrastructure “Qualify for [Artistic] Attention”?’, 41.

[14] Grant Kester, ‘Samvad in Kondagaon’, 193.

[15] Mick Wilson, ‘Autonomy, Agonism and Activist Art: An Interview with Grant Kester’, Art Journal, Fall 2007, 110.

[16] Navjot Altaf, ‘Contemporary Art, Issues of Praxis and Art-Collaboration: Interventions in Bastar’ in Towards a New Art History: Studies in Indian Art eds. Shivaji K Panikkar, Parul Dave Mukherji and Deeptha Achar (New Delhi: DK Printworld, 2003), 93.

[17] Nancy Adajania, The Thirteenth Place, 249.